If Scotland gains independence, the Yes campaign has argued that their preferred option is to keep the Pound Sterling and enter into a currency union with the rest of the UK.

This means sharing the same currency Pound Sterling, and having the same monetary policy. Monetary policy would continue to be set by the Bank of England. There would be no exchange rate between the two countries.

Currency Union with the rest of the UK

However, currency unions are problematic. The Eurozone has been a disaster for many European countries who have been saddled with high unemployment and stagnant economies. See all problems of Euro here.

A big problem with currency unions is that in the absence of a lender of last resort, you face pressure to limit budget deficits. Since the Euro was created, Southern Europe has been pushed into more austerity than is desirable. It has left their economies vulnerable and with limited options to deal with trade imbalances and economic downturns.

The Bank of England governor, Mark Carney insisted a currency union with a sovereign, independent Scotland was impossible. “You only have to look across the Continent to look at what happens… A currency union is incompatible with sovereignty.” (Guardian)

Paul Krugman has stated there are great risks of sharing a currency.

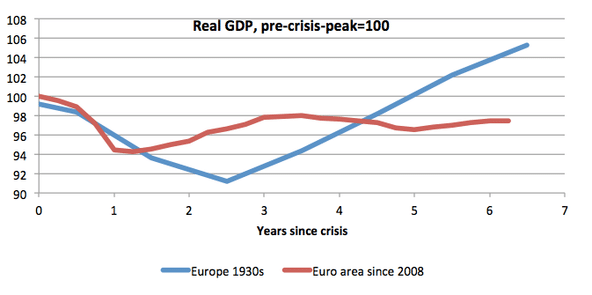

Economists (starting with my late colleague and friend Peter Kenen) have long argued that sharing a currency without fiscal integration is problematic; the creation of the euro put that theory to the test. And the results have been far worse than even the harshest critics of the euro imagined, with euro Europe doing worse at this point than Western Europe did in the 1930s:

Krugman goes on to argue that Scotland’s position could be worse than the Eurzone because there is no guarantee that the Bank of England will be interested in acting like Mario Draghi in his support for debtor countries.

An independent Scotland would be dependent on the kindness of the Bank of, um, England, with no say whatsoever in that bank’s policy. (Scotland and the Euro omen)

Currency unions also exacerbate political tensions. People in southern Europe feel let down by economic policy of the ECB and northern Europe. Germany on the other hand is not happy with the perceived need to bailout its profligate neighbours. Currency unions have not been an effective system for encouraging harmony amongst nations – in fact the opposite. There is a real fear that after independence – Scotland could feel exacerbated and frustrated at being at the mercy of English monetary policy.

But could a currency union between Scotland and the UK work?

There are some reasons to believe that a currency union between Scotland and the UK would work better than the Eurozone.

Firstly, there is much better labour mobility between Scotland and England than say between Greece and Germany. If the Scottish economy is relatively depressed, workers could move south and vice versa.

A big problem of the Eurozone was the divergence in wage costs and relative prices. This left southern Europe uncompetitive but without the option of devaluation to restore competitiveness. This is perhaps less likely to be a problem between Scotland and England. If there is a significant divergence in wage costs, readjustment is easier because of the greater capital and labour mobility.