The great moderation refers to a period of economic stability characterised by low inflation, positive economic growth, and the belief that the boom and bust cycle had been overcome. In retrospect, economists look back on the great moderation in a different light because although inflation was low, there was great volatility in financial markets and asset prices.

Generally, the great moderation refers to the period 1986 – 2006.

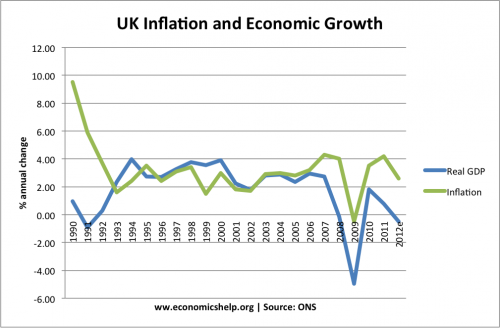

In the UK, the great moderation is considered to be the period 1993-2007 because the UK had a classic boom and bust in late 1980s and early 1990s. The UK experienced 63 consecutive quarters of economic growth between the end of the 1991 recession and the recession in 2008 – the longest continued expansion on record.

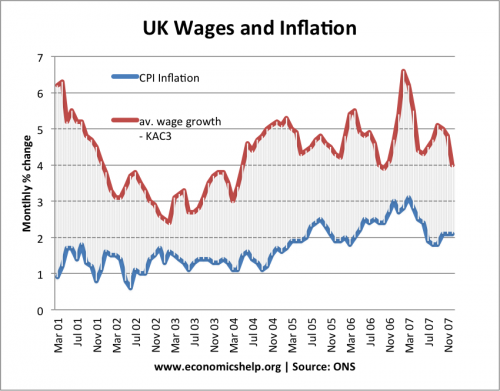

Wage growth

This was typical of wage growth during the great moderation. Average wage growth above CPI inflation causing a steady growth in living standards.

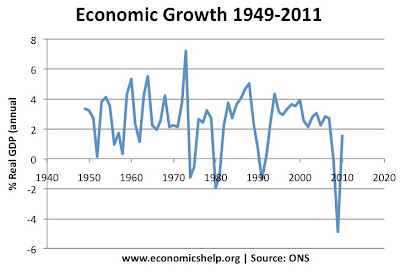

Before the great moderation – boom and bust trade cycles

In the post war period there seemed to be a fairly consistent business cycle. Economies would experience, high growth (a boom), but with high growth came inflation. After a period of inflation, the economy would slow down and sometimes go into recession (see boom and bust). It appeared the business cycle was volatile and inflation difficult to bring under permanent control. The 1970s, saw even greater volatility with oil shocks causing high inflation.

Features of the great moderation

After the volatility of the 1970s and 1980s, the great moderation was seen as a welcome end to this volatile growth and inflation. The great moderation had various aspects.

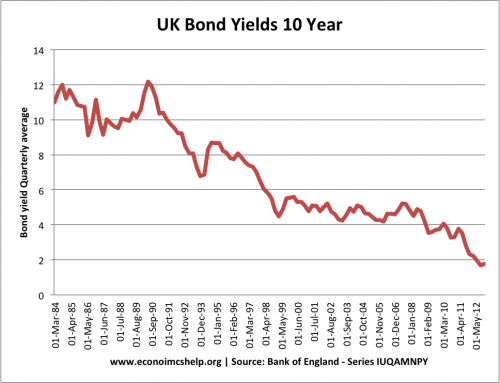

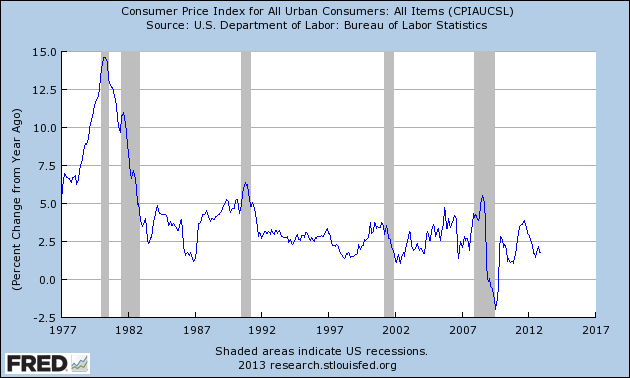

- Low inflation. The most prominent feature of the great moderation was persistently low inflation. It appeared that Central Banks could keep inflation low – without compromising unemployment or economic growth. The Phillips curve had either shifted to the left or was no longer relevant. There was a certain excitement that we were seeing the end of boom and bust.

- Stable growth. With low inflation, we avoided the boom and bust cycles. The UK had their longest period of economic expansion on record 1992-2007. Apart from a minor dip in 2001, the US economy grew strongly during 1986-2006.

- The end of uncertainty and greater risk taking. The benign macro economic situation encouraged investment in both capital and financial investments. During the 1980s and 1990s, there was a period of financial deregulation which encouraged a growth in complex financial derivatives, such as credit default swaps. Financial institutions became willing to take on more risky investments because they were more confident that there wouldn’t be any major economic downturn. Banks became more highly geared as they lent out a greater % of their assets. For more on how macro stability increased risk taking – see Financial instability hypothesis

- Rising asset prices. Asset prices, especially houses, saw a rapid growth in prices. House prices rose because of low interest rates, a stable macro-economy, and growth of mortgage lending. House prices rose faster than inflation, and even faster than incomes. Some were worried house prices were becoming overvalued, but others felt house prices weren’t overvalued because of either limited supply or the growth of new mortgages meant more people could now afford to get a mortgage.