Back in February 2007, I wrote an essay – Evaluate the effectiveness of the MPC in controlling inflation.

The last line was:

MPC have done a good job so far. However the real test may come when there is a rise in structural inflation or global instability.

Given the knowledge of the past five years, how should we update this post,?

1. Central Banks should target inflation and growth

In 2007, I wrote The MPC are responsible for setting interest rates and determining UK monetary policy. They seek to keep inflation close to the government’s target of CPI 2% +/-1 %

But, we should start by adding the full remit of the MPC. In their Monetary policy framework, the Bank of England state, their full responsibility is to:

The Bank’s monetary policy objective is to deliver price stability – low inflation – and, subject to that, to support the Government’s economic objectives including those for growth and employment.

By contrast, the ECB seem to give less importance to economic growth, and seem primarily concerned with low inflation.

“The primary objective of the ECB’s monetary policy is to maintain price stability. The ECB aims at inflation rates of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.”

From: ECB Monetary Policy

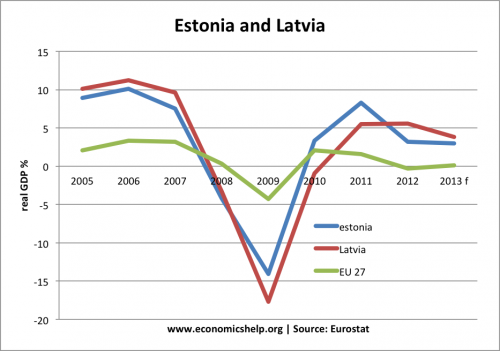

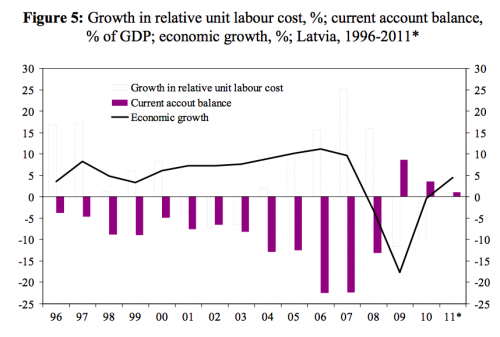

A valid criticism of the ECB during the economic crisis has been the fact they have placed too much emphasis on targeting low inflation. For example, the ECB increased interest rates in 2011, even though the European economy was entering a double dip recession. The ECB have been unwilling / unable to consider more unorthodox monetary tools to boost economic growth.

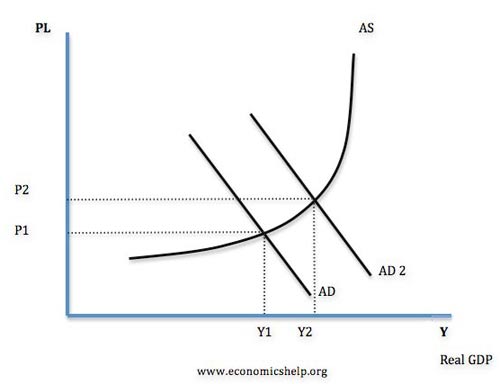

From a narrow perspective of keeping inflation close to the target, the ECB have been quite successful. Eurozone inflation is currently 1.7% and is below the target. However, this period has been very disappointing in terms of economic growth. The EU has entered into a double dip recession. If the ECB had given greater importance to economic recovery and willing to tolerate higher short term cost-push inflation, the EU could conceivably have avoided the double dip recession and done more to reduce the record levels of EU unemployment.

- In evaluation, you could argue that even if the ECB had kept interest rates close to zero, that alone may not have been enough to avoid a double dip recession anyway. However, base rates should not be the only tool that Central Banks consider. Also, the fact that the ECB have been so strident in targeting low inflation, does send signals to European business that policy is more likely to be contractionary.

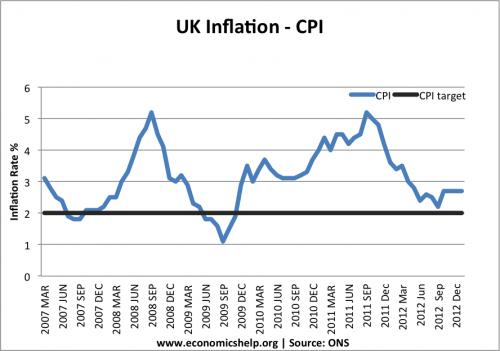

By contrast, the Bank of England has tolerated much higher headline inflation rates.

From the narrow perspective of keeping inflation within target, the Bank of England has frequently missed the target of CPI 2% +/-1. This failure to keep inflation low has also been magnified by the fact that there has been low nominal wage growth. It means that the high inflation rate has led to falling living standards of both those in work, and those on benefits.

However, given the uniquely challenging circumstances of the past five years, it is fair to defend this choice. It made no sense to use interest rates to reduce inflation when the economy was struggling in a prolonged economic stagnation. Firstly this inflation was primarily cost-push. It was due to the effects of devaluation, rising raw material prices and higher taxes. There is also evidence that prices were sticky downwards; the fall in demand didn’t lead to the fall in prices we might have expected.

But, the fact that wage growth was very low, showed there was no underlying demand pull inflation. To religiously keep inflation close to 2%, would have required a potentially very sharp contraction. Given the prolonged recession, you could argue the Bank of England have been too timid in targeting economic recovery. E.g. direct lending to business may have been more successful.

In evaluation, you could argue this might involve the Bank of England extending its original remit, and it would require the government to play a greater role.

2. Limitations of Traditional Monetary Policy

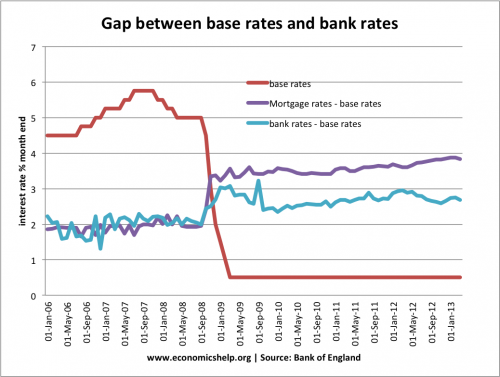

The other lessons of the past five years is the limitations of traditional monetary policy. In normal circumstances a cut in base interest rates from 5% to 0.5% would ensure economic recovery. However, in the great recession, cutting bank base rates has been insufficient.

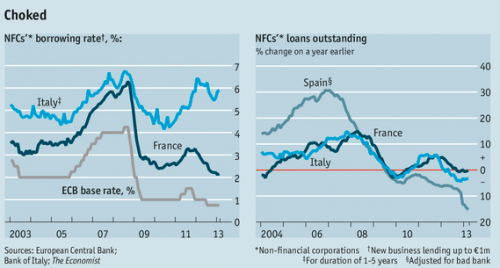

Firstly, commercial bank rates haven’t fallen to match base rates. This has been a particular problem in the Eurozone with bank rates in Spain and Greece, higher than before the crisis. See bank rates and base rates

In the aftermath of the credit crisis, liquidity shortages have meant the supply of credit has constrained lending, investment and growth. In other words reducing the cost of borrowing is insufficient to boost demand, if the supply of credit isn’t there.