After enduring a deep economic crisis, Latvia are poised to be ‘rewarded’ with membership of the Euro in 2014.

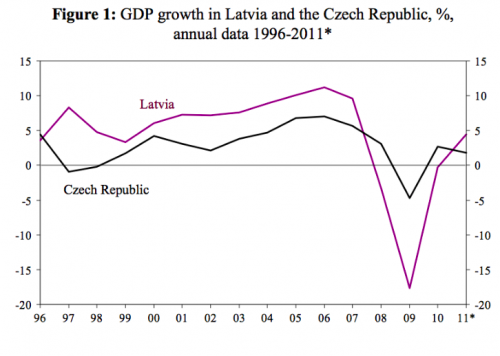

The Latvian miracle story

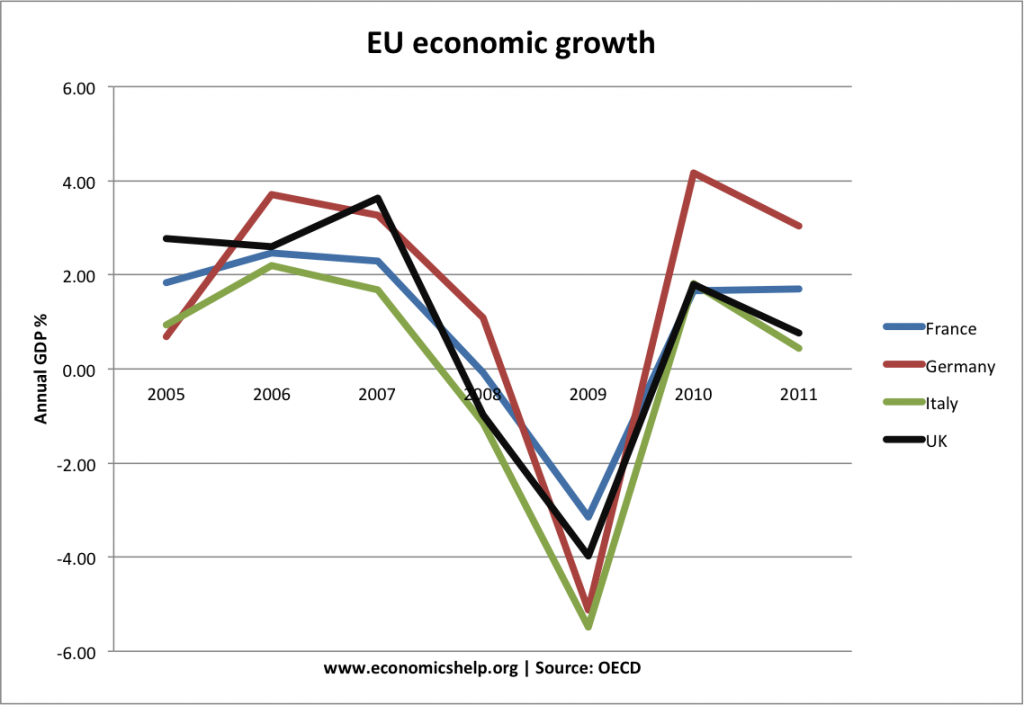

It seems a strange that countries are so keen to join the Euro, when membership of the Euro has been a major factor in creating a real depression amongst many Euro countries. Yet, the debate about Latvian joining seems to be from a parallel universe, where the ongoing crisis is neatly forgotten.

Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis said that the European Commission (EC) had given the go ahead for Latvia for adopt the euro from early 2014. “Joining the eurozone will foster Latvia’s economic growth for sure,” Mr Dombrovskis said. I’m sure that is what the Greek, Spanish and Portuguese political leaders said when they joined in 2000.

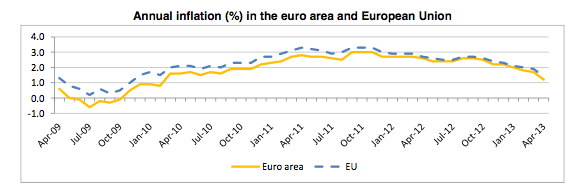

There is opposition – with many in Latvia concerned about ‘rising prices’ after joining the Euro. But, given the experience of the Eurozone in the past few years, rising prices are likely to be the least of Latvia’s concerns over the next few years.

From an outsiders perspective, it’s hard to understand the attraction of joining the Euro. I think the underlying motive must be a desire to join up with Europe and move away from Russia and the East. Given Latvia’s past, this is understandable. What is unfortunate is that being a good European citizen seems to involve joining an unworkable single currency and monetary policy.

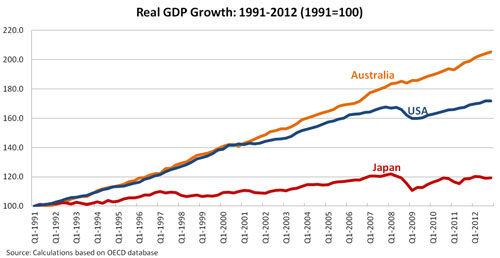

Despite the European obsession with meeting fiscal deficits, there has been much less concern about whether the Eurozone is fundamentally an optimal currency area. An optimal currency area is a geographical area where the benefits of one currency are greater than the downsides. An optimal currency area will need:

- Strong labour and capital mobility

- Lack of geographical barriers

- Fiscal transfers from strong regions to weak ones

- Similar labour costs and similar inflation rates.

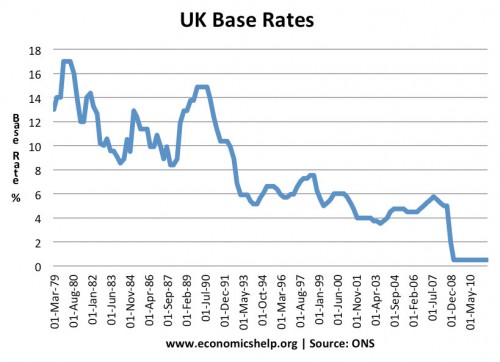

- The ability to cope with a single monetary policy (interest rate)

- The ability to retain competitiveness within the fixed exchange rate.