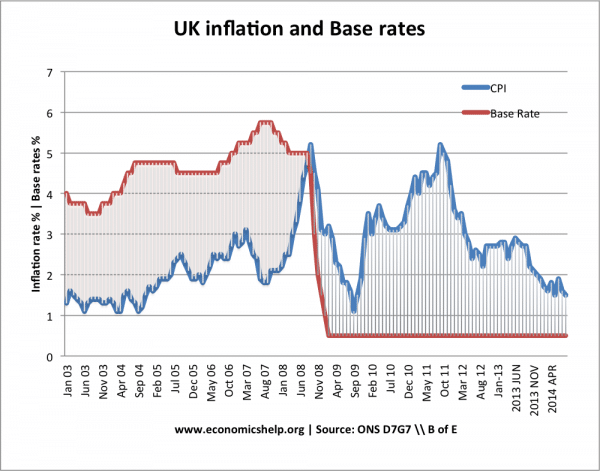

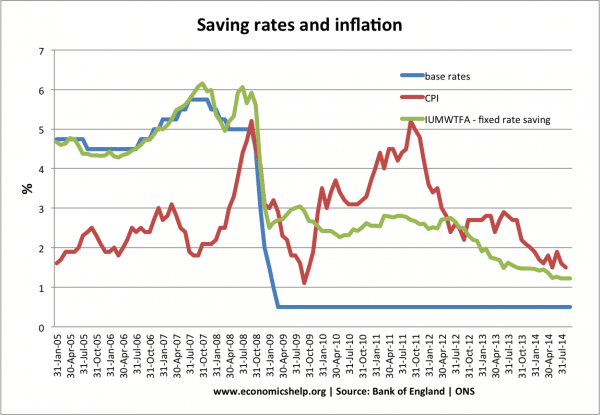

It is not a good time to be a saver in the UK. Interest rates are 0.5% and inflation has been above 2% for a high proportion of the previous five years. Because inflation is higher than nominal interest rates, we are seeing negative real interest rates. This means many savers are seeing a decline in the real value of their savings. Pensioners who are relying on interest payments as income, are seeing a decline in their income.

Inflation and interest rates

In most of the post-war period we have seen positive real interest rates – Base rates above the headline inflation. This means that savers are protected from the effects of inflation.

H0wever, 2008 marks a sharp contrast, with Bank of England base rates falling to 0.5% and inflation reaching above 5%.

In recent months, inflation has fallen to below 2%, but that is still higher than base rates of 0.5%

Effectively, you are getting 0.5% return on your saving, but prices are going up 2%, so the real value of your savings is falling by 1.5%.

Base rates and bank rates

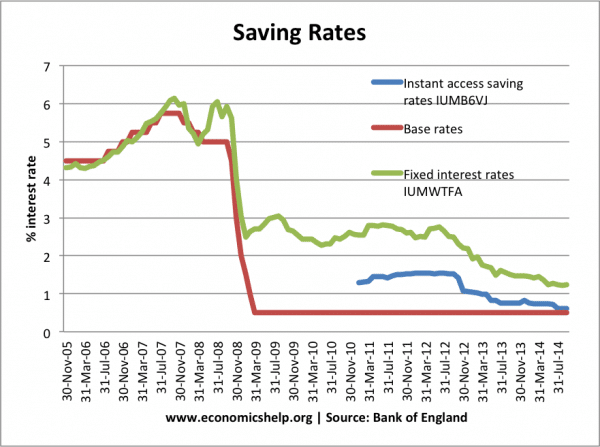

The contrast between base rates and inflation looks very high. But, actually bank savings rates have not fallen as much as base rates. This is because banks were short of money in the credit crunch and were keener to attract deposits than lend money. Therefore, when the Bank of England cut interest rates to 0.5%, commercial banks were not so keen to reduce their own interest rates by as much. Usually commercial bank rates closely follow base rates, but after 2008 we see a break in this correlation.

Source: Bank of England. Series IUMB6VJ | IUMWTFA

In 2008/09, base rates are cut from 5% to 0.5%, but fixed interest rates (series IUMWTFA) only fall to 2.5 / 3%. Interestingly since mid 2012, fixed interest rates have continued to fall closer to 1%. This suggests the banks are less desperate to attract saving deposits and so can reduce interest rates.

It is a similar story with instant access saving rates (series IUMB6VJ) Since mid 2012, rates have fallen from 1.6% to 0.6%. This suggest the financial sector is in better health, but it means a poorer return for savers.

However, if you look around, you can still see higher fixed rates for those willing to ‘lock their money away’

It also depends how much money you can save. For example, according to ‘Money Saving Expert‘ you could get 3.25% if you can put £25,000 away for 5 years. – hardly a great deal, but you would just about get a positive real interest rate.

Should the Bank of England do more for savers?

In the past few years, many groups representing savers have felt they have been ignored – and the government / Bank of England should have done more to give a better rate of return for savers.

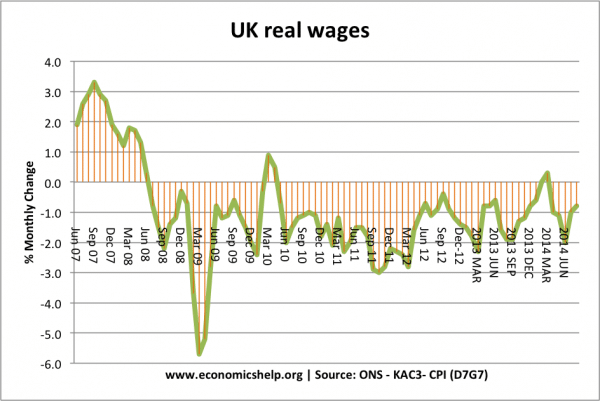

However, the past five years have seen declining living standards for most groups of people – real wages have fallen. Unemployment has been very high. The cost of renting has been very high. Given the general economic decline, savers have not been alone in seeing falling living standards. It is complicated by the fact that people with high levels of saving are more likely to be household owners. Homeowners have seen record low mortgage interest payments and rising house prices, which, to some extent, have offset the fall in the return on savings.

Young people without savings, but paying rent, have seen a bigger squeeze on their living standards.

However, someone who is relying on their savings to pay rent, is definitely in a bind.