Tight monetary policy implies the Central Bank is trying to reduce the demand for money and limit the pace of economic expansion.

A tightening of monetary policy, could involve an increase in interest rates. – Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing and discourage investment and consumer spending. A tightening of monetary policy would be appropriate in a period of positive economic growth and rising inflation, above the inflation target.

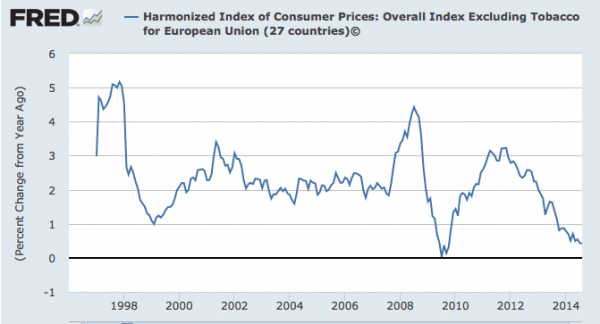

Europe has neither. The Eurozone is facing an inflation rate of 0.4% and weak economic growth. However, monetary policy has been relatively tight.

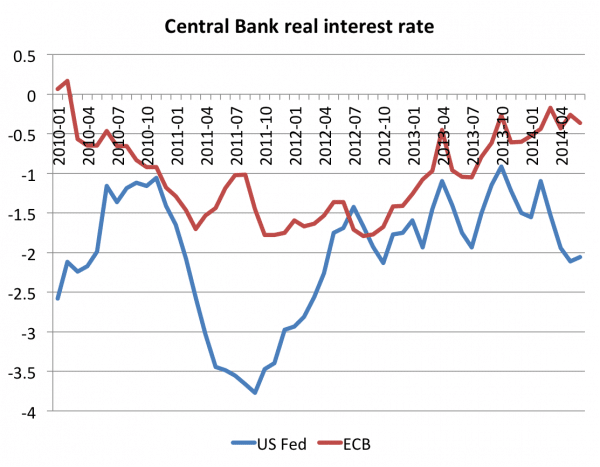

Two graphs from Antonio Fatas help to illustrate this.

Real interest rates in US and EU

Real interest rates are the nominal interest rate – inflation rate.

Therefore, with base rates of 0.5% and inflation of 4%, the US would have a real interest rate of -3.5% – This negative interest rates, in theory, should be more encouraging for people to spend rather than save.

By contrast, the ECB have had higher real interest rates. This is partly because they increased nominal interest rates in 2013, but mainly because European inflation has been lower. The decline in Eurozone inflation to 0.4% has had the effect of increasing real interest rates.

UK real interest rates have been similar to the US. UK inflation has been higher than Eurozone inflation.

The increase in real interest rates in Europe are a serious cause for concern and a good illustration of one of the problems of deflation / low inflation.

With deflation, monetary policy can become unsuitable. Because you can’t cut base rates below zero, monetary policy can become tighter than market conditions allow.

Unfortunately the higher real interest rates and the tightening of monetary policy makes deflation more likely. It is a vicious circle.