The UK national debt is the total amount of money the British government owes to the private sector and other purchasers of UK gilts (e.g. Bank of England).

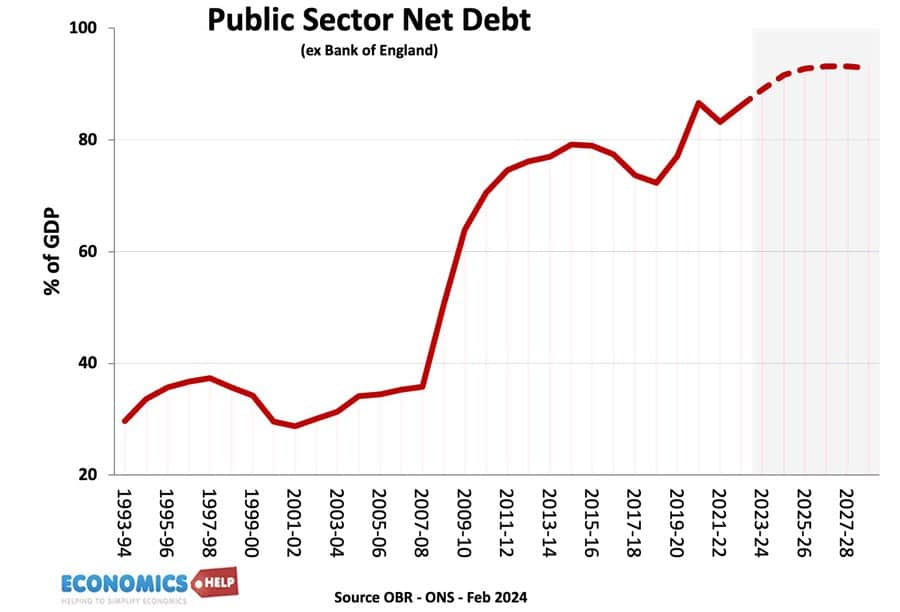

- UK public sector net debt (ex public sector banks) was £2,685.6 billion or 98.1% of GDP (20 Dec 2024).

- The OBR have forecast substantial rises in UK debt over the coming decade because of demographic factors, putting strain on UK spending.

- Source: [1. ONS public sector finances,- HF6X] (page updated 20 Jan 2024)

Source: ONS debt as % of GDP – HF6X | PUSF – public sector finances at ONS

Reasons for National debt

- Enables the government to spend more during periods of national crisis, e.g wars, pandemics, and recessions.

- In a recession, the government will automatically receive lower tax revenues (less VAT and income tax) and will have to spend more on benefits (e.g. more unemployment benefits) This causes a cyclical rise in debt.

- Extra government borrowing during a recession can help provide fiscal stimulus to promote economic recovery. By borrowing and then spending more, the government is injecting demand into the economy and this can help to reduce unemployment. This is known as fiscal policy and was advocated by J.M. Keynes.

- Strong market demand for government debt. Private investors buy gilts because they are seen as risk-free investments and there is also an annual dividend from the bond yield. Since 2009, there has been strong demand despite very low-interest rates, meaning the government can borrow very cheaply.

- Finance investment. The government could borrow to finance public investment projects that can lead to higher growth in the future.

- Political convenience. There is usually political pressure to cut taxes and increase government spending. Allowing debt to rise can be a way for the government to avoid difficult choices.

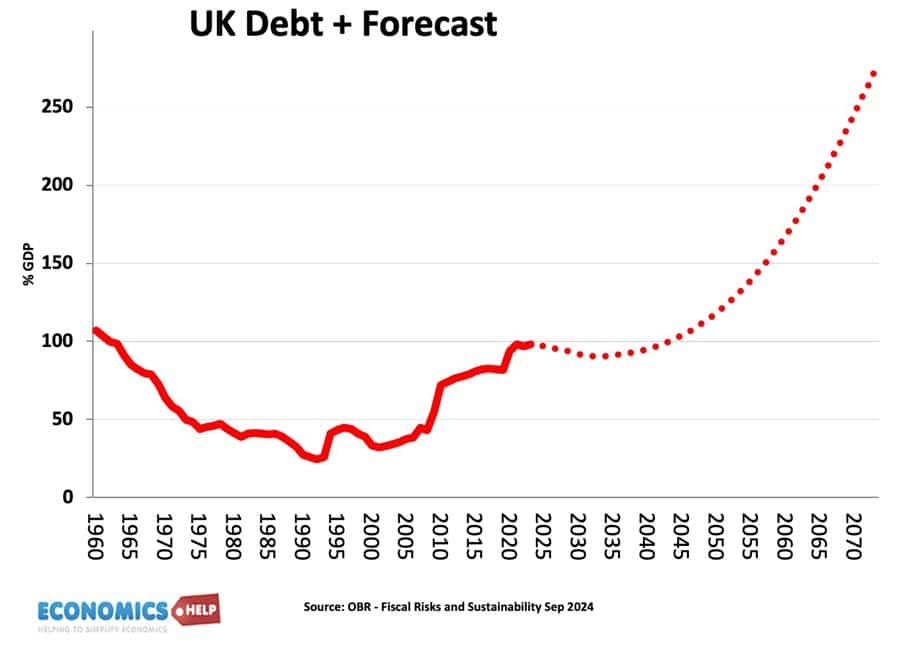

Forecast for the National debt?

Source: Fiscal risks and sustainability – OBR – Economic and Fiscal Outlook Oct 2024

The OBR have forecast that, on our given trajectory, UK public sector debt could reach 350% of GDP within 50 years. The pessimistic outlook for national debt is made because

- An ageing population and demographic changes will put increased pressure on government spending, notably health care and pension spending.

- A smaller working population will limit UK’s productive capacity.

- Stress on finances from geopolitical events, such as frostier relations with China, Russia and the Middle East.

- Higher energy prices

- Costs of climate change.

- Declining tax revenues from petrol in a decarbonising economy.

- Low productivity growth of UK since the financial crash of 2009

- Recent boost to debt from the financial crisis and one-off cost of Coronovirus pandemic, which cut tax revenues and required government support for lockdown measures.

UK debt in context

Predicting debt for the next 50 years is difficult since we don’t know what kind of productivity improvements may come, e.g. continued gains in renewable energy may reduce the burden of higher oil and gas prices. Equally, the costs of environmental change could be worse.

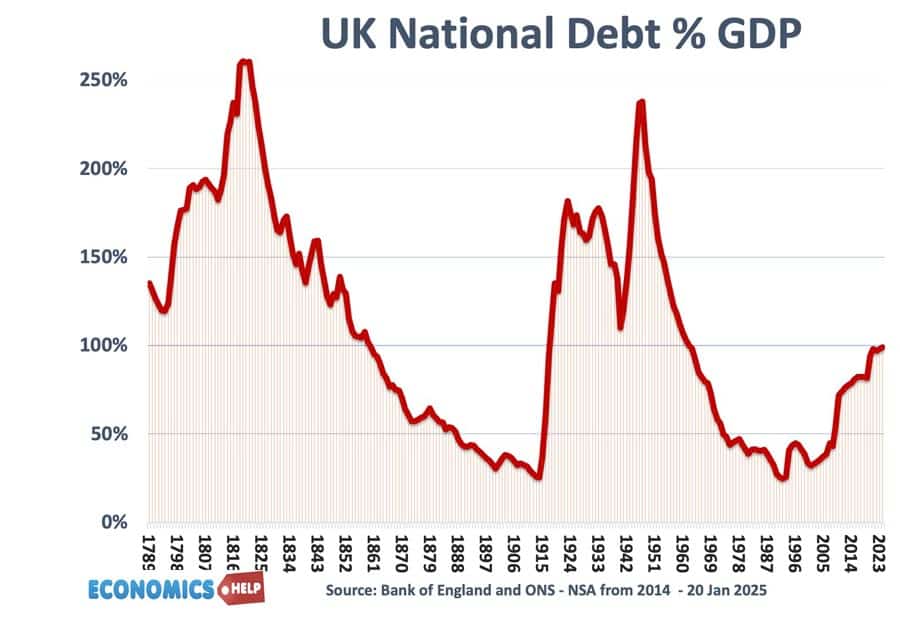

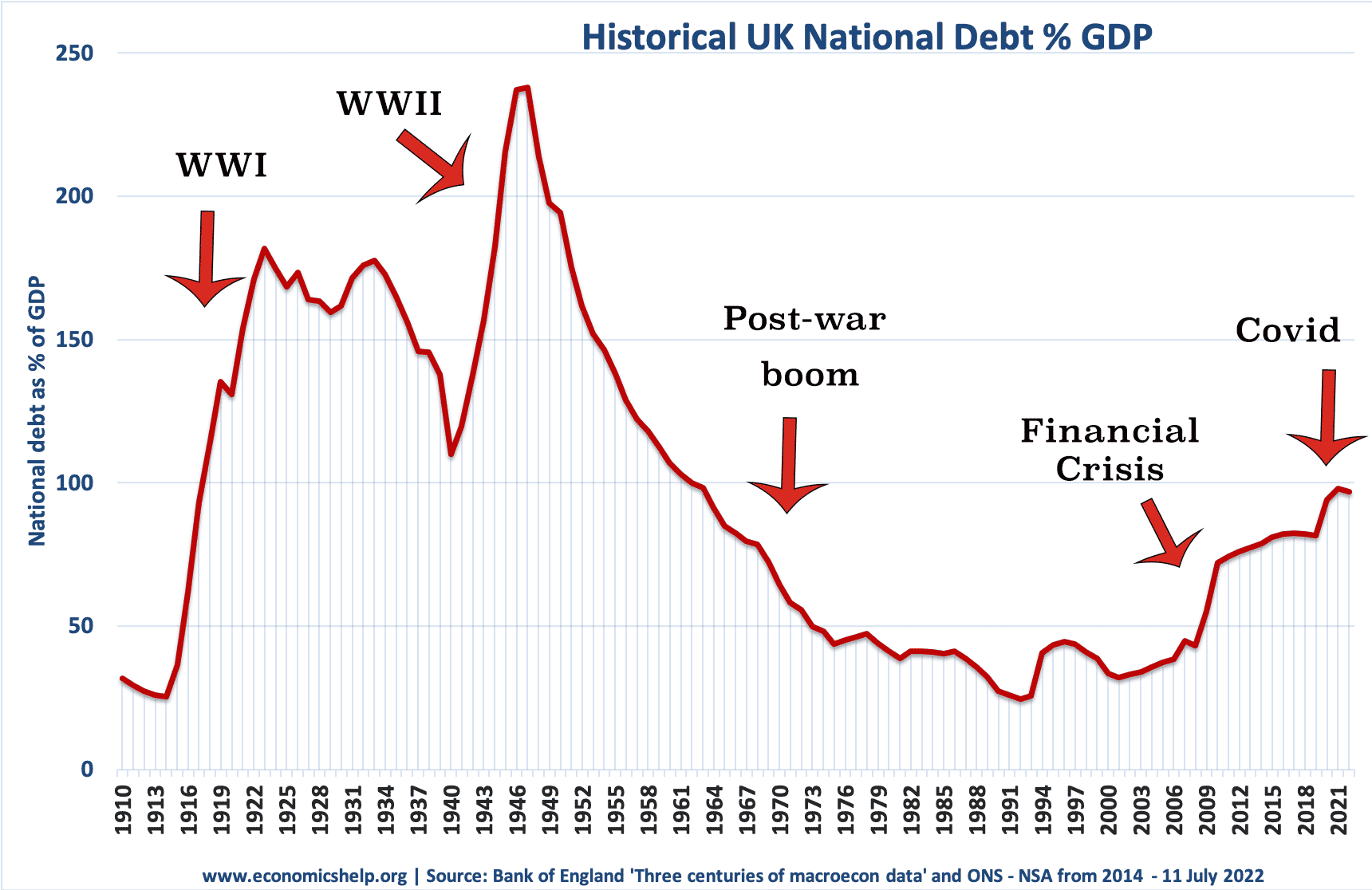

History of the national debt

Main article: History of UK national debt

UK national debt since 1900

Source: Reinhart, Camen M. and Kenneth S. Rogoff, “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis,” NBER Working Paper 15795, March 2010. and OBR from 2010.

These graphs show that government debt as a % of GDP has been much higher in the past. Notably in the aftermath of the two world wars. This suggests that current UK debt is manageable compared to the early 1950s. (note, even with a national debt of 200% of GDP in the 1950s, UK avoided default and even managed to set up the welfare state and NHS.

Debt reduction and growth

The post-war levels of national debt suggest that high debt levels are not incompatible with rising living standards and high economic growth.

- The reduction in debt as a % of GDP 1950-1980 was primarily due to a prolonged period of economic growth. See: how the UK reduced debt in the post-war period

- This contrasts with the experience of the UK in the 1920s when in the post First World War, the UK adopted austerity policies (and high exchange rate) but failed to reduce debt to GDP. Debt in Post-First World War period.

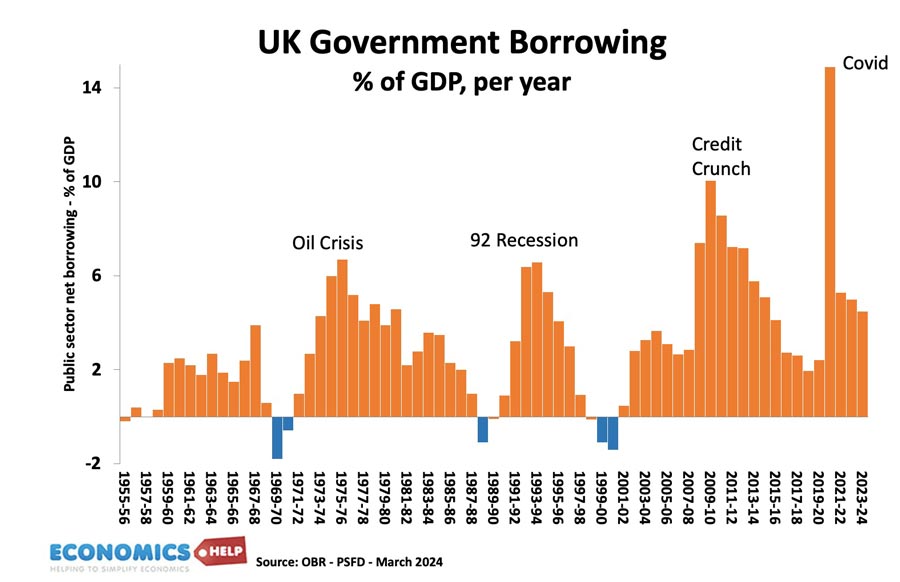

Budget deficit – annual borrowing

This is the amount the government has to borrow per year.

- Government

- borrowing in the financial year to December 2024 was £129.9

Annual borrowing since 1950. Figures for 2023-24 are forecasts (and rather optimistic!)

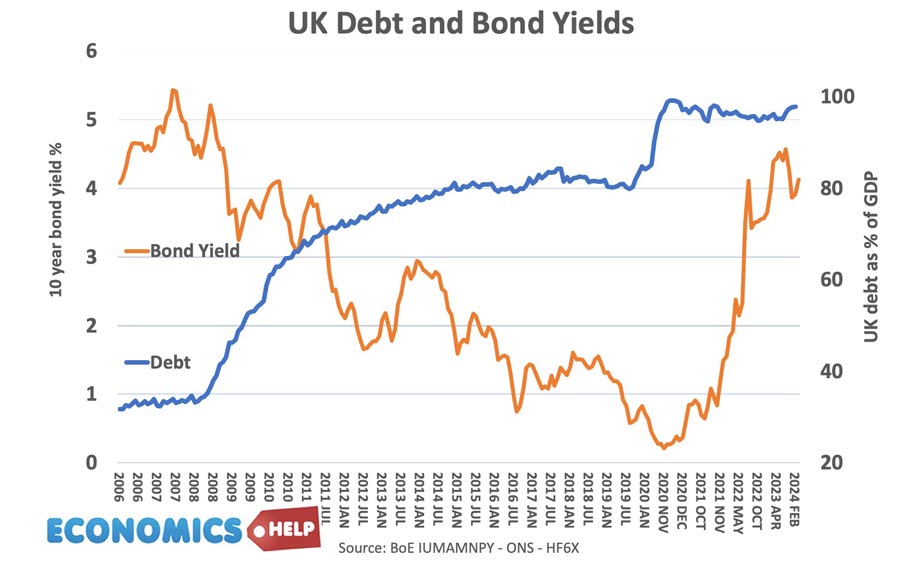

Debt and bond yields

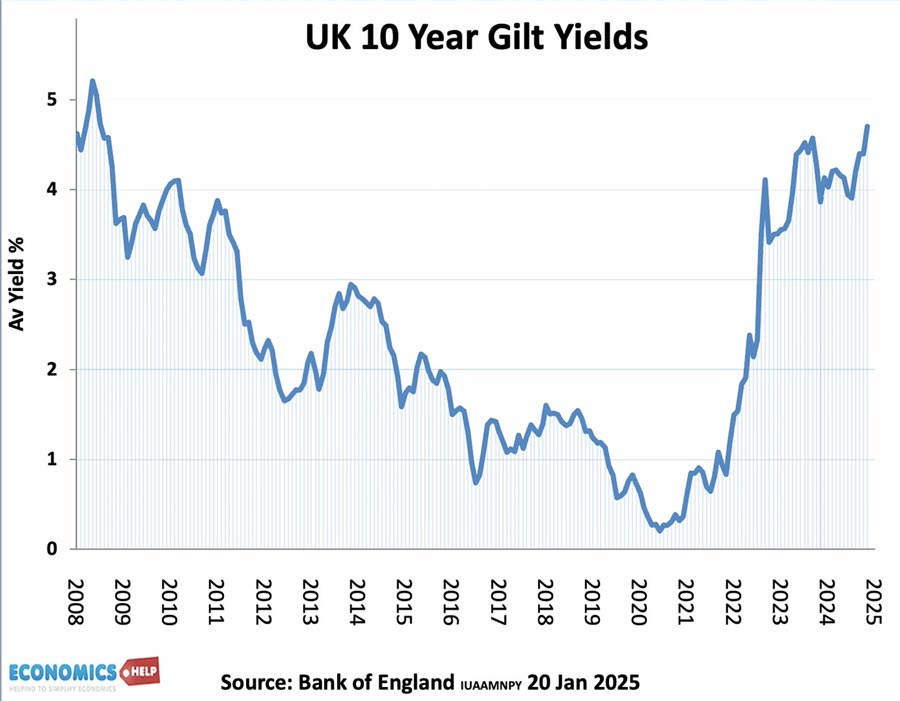

Bond yields a the interest that the government pay bond/gilt holders. It reflects the cost of borrowing for the government. Lower bond yields reduce the cost of government borrowing.

Between 2007 and 2020, UK bond yields fell. Countries in the Eurozone with similar debt levels saw a sharp rise in bond yields putting greater pressure on their government to cut spending quickly. However, being outside the Euro with an independent Central Bank (willing to act as lender of last resort to the government) means markets don’t fear a liquidity crisis in the UK; Euro members who don’t have a Central Bank willing to buy bonds during a liquidity crisis have been more at risk to rising bond yields and fears over government debt.

See also: Bond yields on European debt | (reasons for falling UK bond yields)

Since 2021, bond yields have risen due to pick up in inflation

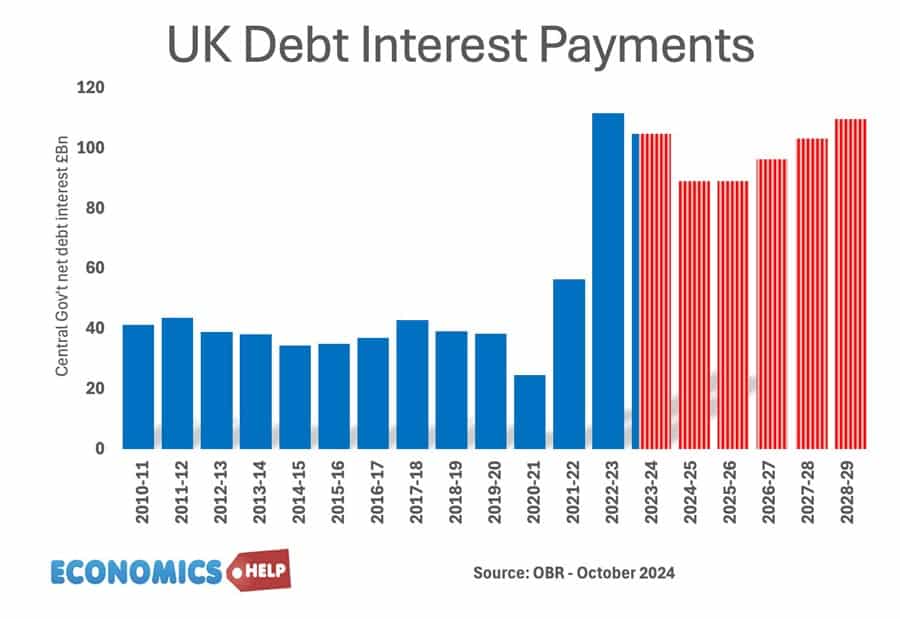

Cost of Interest Payments on National Debt

The cost of National debt is the interest the government has to pay on the bonds and gilts it sells. According to the OBR in 2023-24, debt interest payments will be £108 billion. (3.2% of GDP) or 5.2% of total spending. It is lower than in previous decades because of lower bond yields.

See also: UK Debt interest payments

The era of low interest rates post 1992 helped to reduce UK debt interest payments as a ratio of government revenue. However, with interest rates and borrowing increasing – debt interest cost have increased significantly.

Potential problems of National Debt

- Interest payments. The cost of paying interest on the government’s debt is very high. In 2011 debt interest payments will be £48 billion a year (est 3% of GDP). Public sector debt interest payments will be the 4th highest department after social security, health and education. Debt interest payments could rise close to £70bn given the forecast rise in national debt.

- Higher taxes / lower spending in the future.

- Crowding out of private sector investment/spending.

- The structural deficit will only get worse as an ageing population places greater strain on the UK’s pension liabilities. (demographic time bomb)

- Potential negative impact on the exchange rate (link)

- Potential of rising interest rates as markets become more reluctant to lend to the UK government.

However, government borrowing is not always as bad as people fear.

- Borrowing in a recession helps to offset a rise in private sector saving. Government borrowing helps maintain aggregate demand and prevents a fall in spending.

- In a liquidity trap and zero interest rates, governments can often borrow at very low rates for a long time (e.g. Japan and the UK) This is because people want to save and buy government bonds.

- Austerity measures (e.g. cutting spending and raising taxes) can lead to a decrease in economic growth and cause the deficit to remain the same % of GDP. Austerity measures and the economy | Timing of austerity

Who owns UK Debt?

The majority of UK debt used to be held by the UK private sector, in particular, UK insurance and pension funds. In recent years, the Bank of England has bought gilts taking its holding to 25% of UK public sector debt.

Source: DMO Debt Management Report 2022/23

- Overseas investors own about 28% of UK gilts (2022).

- The Asset Purchase Facility is purchases by the Bank of England as part of quantitive easing. This accounts for 26% of gilt holdings.

Total UK Debt – government + private

- Another way to examine UK debt is to look at both government debt and private debt combined.

- Total UK debt includes household sector debt, business sector debt, financial sector debt and government debt. This is over 500% of GDP. Total UK Debt

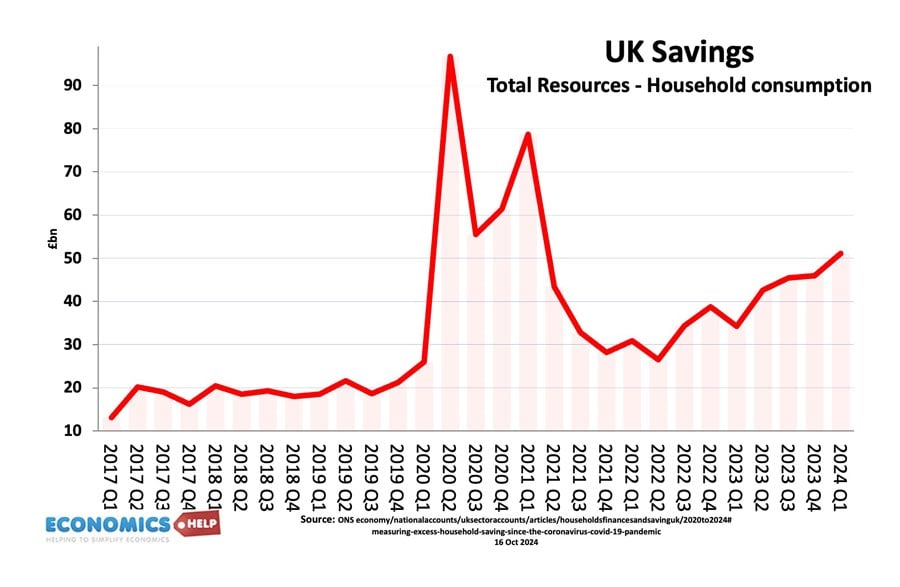

Private sector savings

When considering government borrowing, it is important to place it in context. From 2007 to 2012, we have seen a sharp rise in private sector saving (UK savings ratio). The private sector has been seeking to reduce their debt levels and increase savings (e.g. buying government bonds). This increase in savings led to a sharp fall in private sector spending and investment. The increase in government borrowing is making use of this steep increase in private sector savings and helping to offset the fall in AD. see: Private and public sector borrowing

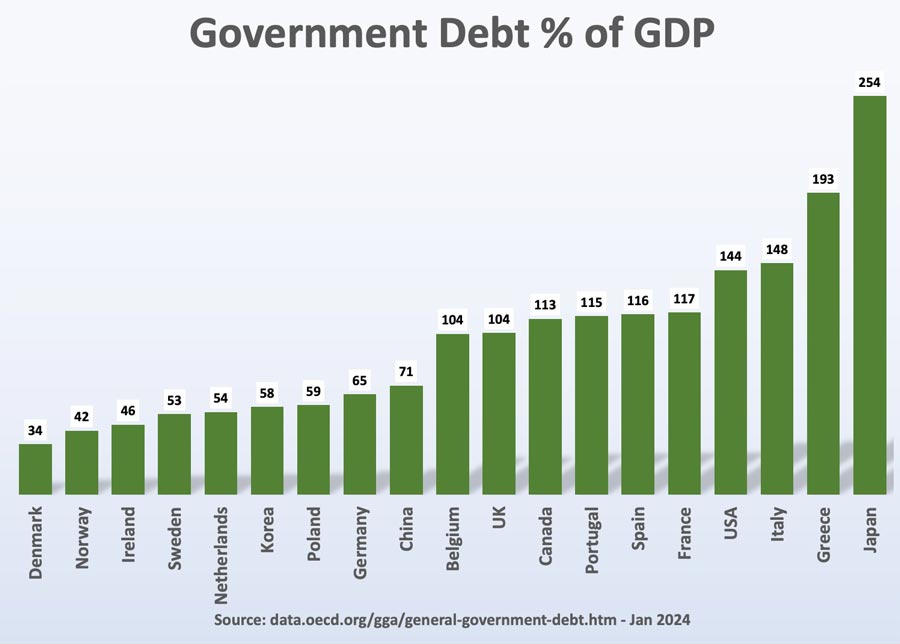

Comparison with other countries

Although 107% of GDP is high by recent UK standards, it is worth bearing in mind that other countries have a much bigger problem. Japan, for example, has a National debt of 256%, Italy is over 157%. The US national debt is over 132% of GDP. [See other countries debt].

How to reduce the debt to GDP ratio?

- Economic expansion which improves tax revenues and reduces spending on benefits like Job Seekers Allowance. The economic slowdown which has occurred since 2010 has pushed the UK into a period of slow economic growth – especially if we consider GDP per capita growth. Therefore the further squeeze on tax revenues has led to deficit-reduction targets being missed.

- Government spending cuts and tax increases (e.g. VAT) which improve public finances and deal with the structural deficit. The difficulty is the extent to which these spending cuts could reduce economic growth and hamper attempts to improve tax revenues. Some economists feel the timing of deficit consolidation is very important, and growth should come before fiscal consolidation.

- See: practical solutions to reducing debt without harming growth

Other countries debt

See also:

When you compare the UK debt problems to other countries, it really doesn’t seem that bad. Not good, of course, but it’s a reminder that there are MANY people who are worse off and struggling wit debt.

The above article omits to mention that the real or inflation adjusted interest we pay on the debt is zero approximately.

Another point that will have debt-phobes completely flummoxed is thus. If inflation is near zero and the real or inflation adjusted rate of interest paid on the debt is zero, then then the debt becomes the same thing as money (monetary base).

You’re still paying a thousand pound a year out of every taxpayers money. But that’s okay because their wages are going up by that! Prick!

I think I get this Ralph but can you explain further.

Are you saying that because the debt isn’t bearing any additional liability (ie interest) then defacto is just a promise to repay which is on effect the same as.. Well money. How can increasing the amount of money in supply also not affect the inflation environment.?

I would like to understand more.. Thanks 🙂

is this right and is it american

ok,

So if we’re a trillion in debt and yet the government always pays its lenders on time, how come we’re a trillion pounds in debt??

The government is paying off old loans (Bonds) but taking out new ones at the same time.

Yo’re not meant to get out of debt – jeez!

I am impressed with the clarity of your explanations. However, one thing that eludes me is in connection with the so-called National Debt, currently running at over £1.5 trillion (gross). About a quarter is due to the Bank of England (£375 billion) and arises from QE. The rest is due to Overseas Lenders, Insurance Companies and Pension Funds, Building Societies, Investment Trusts, Local Authorities and Public Corporations and Private Individuals. But I can’t seem to find out exactly what is due to each of these categories. Am I being stupid?

Even a FOI request to HM Treasury hasn’t helped. Why is it a secret?

This may help

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1407/economics/who-owns-government-debt/

Martin , under some agreed convention Govt are barred from printing currency. So the £ 375 billion QE debt held by the BOE will need to be repaid by the govt. and the QE will be extinguished . Therefore the govt will need to find money to do this.

This is from an analysis of Public Servant’s Pension debt from 2012:

The results showed the extraordinary sums that Britain has committed to pay its future retirees. In total, the UK is committed to paying £7.1 trillion in pensions to people who are currently either already retired or still in the workforce.

Bet you wish you’d never asked!

Born into bondage

Hi, just want to say that I have stumbled upon this page, and found it to be very succint in explaining how government debt works!

I have one quick question though; what determines the rate of interest (or yield) that the government pays on its gilts? Do credit rating agencies play a part? Or is it simply demand and supply?

If bond yields increase, does that have an effect on bond rates in general?

The “market” decides by analysing what risk there is to lending and the BofE base rate and that decides interest rates. Recently George complained that he could borrow money cheaper in the bond market than he could from the the public’s Premium Bond holdings so “Ernie’s” interest rate was dropped as was the monthly prize pot!

Debt interest seems, at first, to be just an expense, but it is INCOME to those who receive it.

Payment of interest just shuffles money around, it doesn’t consume resources.

I thought the article was really good until I reached the line where you said, “However, these pension liabilities are not things the government are actually spending now. Therefore, there is no need to borrow for them yet. It is more of a guide to future public sector debt. I don’t accept the fact that future pension liabilities should be counted as public sector debt”. Then I had to chuckle. It’s a bit like me saying I’ve put money aside supposedly for my child’s university education, spent it on whatever, and I don’t have a problem!?!

On the last figures I saw, the OBR estimate for total government pension obligations was well north of £5 trillion which are presently being funded at a rate of 6% up until late 2013. Of these public sector employee pension liabilities are only being funded at around 58% of GDP. As well you seem to have left out social security related liabilities that are unfunded are estimated still in the range of £3.8 billion. I seriously question from where you think the money to pay for this is going to come especially as household debit is close to 100% of UK GDP? These numbers are as bad as many of the other usual suspects (i.e. the PIIGS) in the EU. It’s only that because of the Greek drama (and interests rates are abnormally low due to QE) that no one is actually paying attention to it!

So what’s missing?

The 9,200 bn that the state owes the public for pensions.

But that’s money for the plebs.

Gilts on the other hand, that’s money owed to the bankers. That’s way more important isn’t it.

Just worry about the bankers.

The plebs? They can go without.

I have a different worry. This is that as our manufacturing sector continues to shrink, that the UK economy may not be able to increase EXPORTS the way it once could, eg Japan. In that case, we may not be able to pay off our debt as we used to be able to. This will be especailly true if the low pay countries in Asia continue to seize increasing fractions of the markets for these manufactures. Thats why I regretfully find myself supporing SOME version of austerity. Its very easy for Paul Krugman to criticise this, but i don’t see him looking at this aspect. Critical comments welcome.

Ian Mordant

It is isn’t exports of manufacturing goods which pay for the national debt.

Is it me?? Whatever happened to, cutting the cloth to suit the needs? Or similar sayings that I used to hear. Has the world generally gone mad? In 1969 I could borrow money from my friendly bank manager on the understanding it would be paid back in full, within a specific time limit of, say 4 weeks,,,and it always was,,,then the banking system seemed to change,or maybe I changed but the new manager was not interested in short term lending and he then wanted to loan me three times the amount for a full year and get the full interest for the said year,,,it worked for the bank but not for me, I never borrowed again and have been fortunate to retire after working all my life, with no debt. Ok I only have my std pension but I just manage and no more,,,, it seems the world is just like Greece,,,in the mire, and if the west is not there now, it soon will be. Charity starts at home,,,don’t give total control to your best friend of all your dealings or you might get a shock,,,ie the EU. I have now stabled my high horse and thrown the key away,,,good luck to you all.

Thanks for the information, succinctly written. The UK government are borrowing every year to pay off the previous year’s shortfall. This borrowing incurs an interest charge, so it cannot be counted as “income”, and every year we are borrowing more to pay off the loans. This is ” Wonga loans” economics.

The deficit is just savings. That is how sovereign banking works. See page 43 of Warren Moslers work the seven deadly innocent frauds of economic policy. Warren worked inside banking becoming a billionaire in the process! http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

So governments can never get into debt because they can create as much money as they like at any time. If that was the case there would be no need to sell bonds, they wouldn’t exist because the government would simply create the money. But bond markets do exist so either Warren Mosler is a fool or I am.

Issuing bonds IS the government creating money isn’t it? Am I missing something here?

They do need to save bonds. To people who want a safe place to store pounds. But they dont need to sell bonds to raise income. No.

Warren Mosler is a fraud. I quote the “fact” he presents to support his first assertion.

“Federal government spending is in no case

operationally constrained by revenues, meaning that there is no “solvency risk.” In other words, the federal government can always make any and all payments in its own currency, no matter how large the deficit is, or how few taxes it collects.”

This is nonsense. Governments can and do default. Argentina and Russia to give two fairly recent examples. Also, the ability to print money does not mean you can in reality repay a debt. If the government borrows money in its own currency, then devalues that currency to the point where it is worthless, then repays the debt in the worthless currency, has the lender been repaid? I think not. You really can lose money lending to a government. Which means a comment I observed below saying gilts are 100% secure is also wrong.

Glad someone actually knows what they are talking about,…

Governments can choose to default but they dont have to. The BOE the US federal bank have all explained that is impossible for those central banks to be forced into insolvency. SO Mosler is right. IT is a fact. We get our income from govt, govt doesnt get income from us.

It is not a fact, we do not get our income from governments (it doesn’t even make sense) Most of the money is not created by the government or indeed the central bank. In the crudest terms Most is created by banks lending it, and then re-lending the money when it is re-deposited. Any one who says that borrowing more money is the answer when you are already borrowing more than £1,500 per second does not know what they are talking about. Let me say that again we are currently borrowing more than £1,500 every second of every days, yes even when you are sleeping. Borrowing more is crazy, we are spending more than we can afford.

in its own currency,

Countries that borrow in other currencies may have problems if they cannot earn (or buy) the foreign currency.

Hello, Public sector net debt (ex. public sector banks) was £1,606.9 billion.

In this number is excluded the amount of gilts held by boe (357 mld of sterling), beacause with consolidation was removed?