AI is coming for your job. It doesn’t matter if you are taxi driver, accountant or god forbid writer and podcaster, AI and chat bots are going to be able to do it better. Goldman Sachs forecast 300 million jobs could be lost globally. That’s 2/3 of all jobs at risk of some degree of automation. Yet, it’s not all bad news. This new technology will lead to a rise in productivity and a 7% rise in global GDP. But, the big question is who will benefit from this? Well, the big tech firms are already seing a surge in profit and stock market valuations on the grounds AI will inevitably lead to ever higher profit. But as profits rise, median wage seem stagnant. This is the stuff of a dystopian nightmare. Inanimate robots taking your job and powerful tech monopolies gaining all the profit. Leaving us to scrablling around for scraps from the table.

Yet, there is a solution. A universal basic income funded by the profits and benefits of technology will give everyone a basic standard of living. Rather than having the constant fear of losing means tested benefits, individuals will have the freedom and confidence to develop their skills, interests and personal business. The best thing about a universal basic income is that it avoids complex set of administration and the incentive destroying nature of means tested benefits. In recent years, the UK has seen a rise in inactivity rates. In particular, the rate of people claiming sickness benefit is rising. It means the expected sickness benefit bill is set to keep going up from £40 to £70bn in a few years, leaving us with the worst of both worlds. Higher benefits, less people in work and a distorted incentives to stay out of work.

Support for some kind of universal income has ranged from libertarians like Milton Friedman to social activists like Martin Luther King and the godfathers of AI like Sam Altman. But whilst a UBI paid for by tech giants sounds like a new utopia. It would also be very expensive and critics argue it could lead to a people dropping out, living off free hand outs and smoking dope.

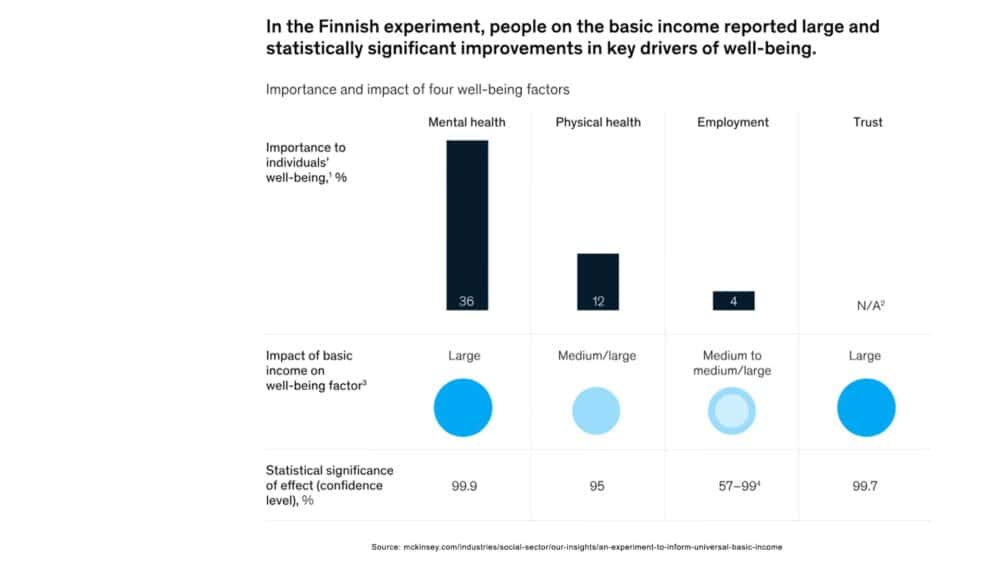

Fortunately, there are real life studies. From 2018 to 2020, Finland ran an experiment with 2,000 unemployed people receiving a monthly payment of €560, no conditions, no means tests. The results were promising. Compared to a control group, there was a remarkable improvement in reported mental health and physical health, and there was a statistically signficant increase in employment. Fears that a universal income could make people lazy is not borne out by results. It seems people do want to take part in meaningful work. Since 1982, Alaska has had a long-running universal basic income programme, funded by oil revenues. Every citizen gets an annual stipend varying from $1,000 to $3,500. It is credited with reducing poverty 20% and having a positive effect on increasing part-time work. Full-time work rates largely unaffected. In particular, it gives workers the confidence to spend more time getting a job actually suited to their job. Yet, Alaska has shown there is potential drawbacks. In 2018 Republican Mike Dunleavy ran for governor, promising to pay everyone $6,700. Unsurprisingly he won the election by a landslide. But, the money wasn’t there. To get higher funding, he ended up cutting spending on health, transport and infrastructure, and in the en,d they never got close to paying the promise. UBI can start to distort the political system.

And this is the dark side of a universal basic income, everyone likes getting the money part, but how do you actually fund it? In 2020, a UK parliamentary report stated that to give every adult £100 a week and every child £50 a week, would cost around £314 billion a year. At the time, the total welfare bill was £225bn. That’s just a small matter of raising £89bn in taxes. An extra 11p on income tax would do it. Means testing winter fuel saved £1bn. Creating a universal basic income would be popular, but higher taxes would not. Taxing profits of big tech firms would be a start, but that would need a high level of international co-operation that probably isn’t there. There are ways to tackle the wealthy if the will is there. But, there are other demands for public spending, – health care, defense and building houses.

But, if we could find a way to fund it, there are many real benefits Results of a three-year long US study into a UBI, backed by Sam Altman, the AI investor, found people had more time to organise their lives and make decisions about what was important to them. As economists we tend to measure things by easily measurable metrics like GDP, hours worked and income, but, that is only one aspect of life. UBI could enable a greater work life balance, which ultimately helps productivity and quality of life. It could also support people to spend more time caring for the elderly, a looming problem.

But, if AI is disruptive as some fear, it could massively alter the nature of labour markets. Knowing the streets of London, used to give London cab drivers a premium range, but with GPS, that is lost. It is only a matter of time, before self-driving cars take the job completely. The promise of tech is massive productivity gains, but, there is no point in having this if many lose out and the gains are in the top 1% of the population. Professor Hinton the godfather of AI said “my guess is in between five and 20 years from now there’s a probability of half that we’ll have to confront the problem of AI trying to take over”. Perhaps we’ll need a UBI to be able to organise the fight back.

AI Threat Overblown?

But, is the threat of AI overblows? we have been worrying about technology taking jobs, since the mechanical loom caused job losses amongst traditional weavers. In 1920, there were 1 million coal miners, technological change has caused all these jobs to be lost. But, is society really worse off as a result? AI will cause a similar shift in the labour market. It’s easy to think of the jobs lost, but it is harder to envisage the new jobs that will be created. To think AI would lead to a period of mass unemployment is a mistake. It might just help some automate boring jobs and enable doctors to spend more time treating patients.

Universal benefits have a great advantage in that they are simple and no distortionary effects, But we can’t necessarily rely on just universal benefits. For example, the government is planning to cut disabled benefits, but you could argue being disabled and sick creates higher costs of living, such as the need to pay for carers. Secondly, if you live in a cold, expensive rented property, then you might need more housing benefit than someone who lives in a house with mortgage paid off. You can’t just replace all benefits with a UBI.

Sources:

https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/07/15/how-likely-universal-basic-income-is-in-the-us.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cnd607ekl99o

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2020-0096/

https://www.theregister.com/2024/07/23/sam_altman_basic_income/

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/9/5/20849020/alaska-permanent-fund-universal-basic-income