Interest rates are a tool of monetary policy. When the economy is overheating, the Central Bank can raise interest rates to cool demand and avoid an inflationary boom. In an ideal world, the Central Bank would make small adjustments in interest rates to fine-tune the economy and avoid booms and busts, but the situation the Bank of England finds itself in is very challenging.

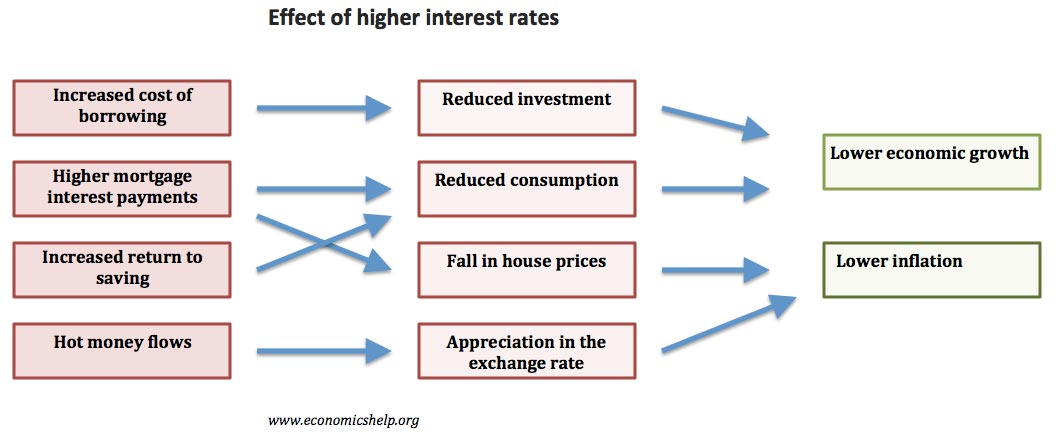

In the UK, even a small change in interest rates can have a significant impact on demand and economic growth. Higher rates increase the cost of borrowing, and in particular the cost of mortgages. Many households with loans or mortgages will have to pay more on monthly repayments, squeezing their disposable income and reducing spending.

Why would rising interest rates be particularly damaging at the moment?

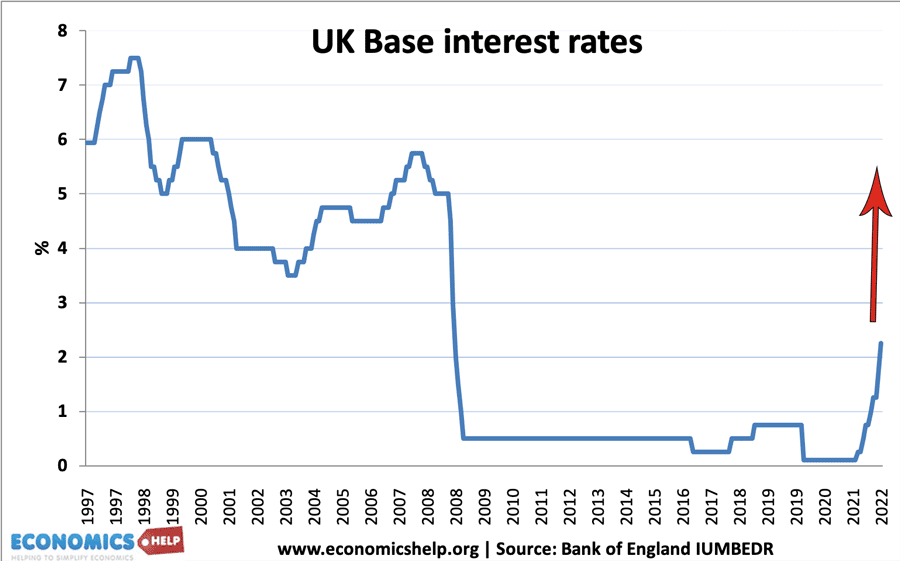

A sharp break with the past 15 years. Homeowners have become used to ultra-low interest rates. When interest rates are 0.5% for over a decade, households and firms make decisions based on interest rates staying low. People have taken out large mortgages and based the affordability of repayments on low rates. If interest rates rise from 0.5% to 6%.

A £270,ooo, 25-year mortgage.

- At 2% interest rate – average monthly repayments £1,144

- At 6% interest rate – average monthly repayment £1,740

Not everyone is on a variable mortgage. Many are on 2 year fixed with will expire over the next 18 months. For many households, a £600 increase in monthly payments will come as a shock and could lead to a catastrophic decline in disposable income. Analysts worry that such a mortgage shock will cause a significant fall in house prices as repossession rates rise and investors seek to offload high mortgage properties.

Also housing analysts argue that rising mortage costs would put pressure on landlords to increase rents, so it wouldn’t just be those with mortgages affected.

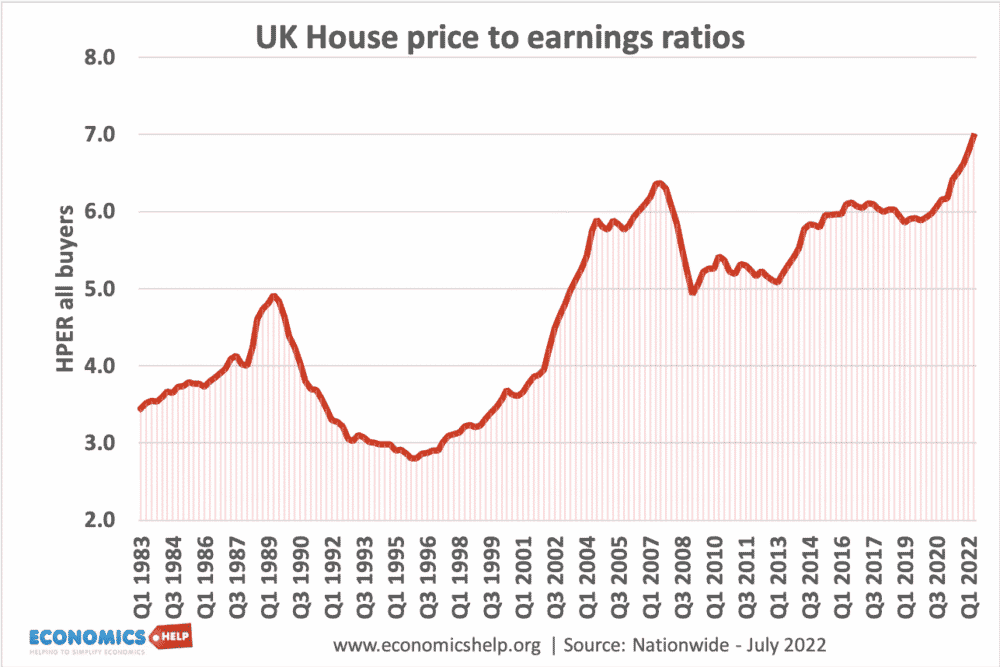

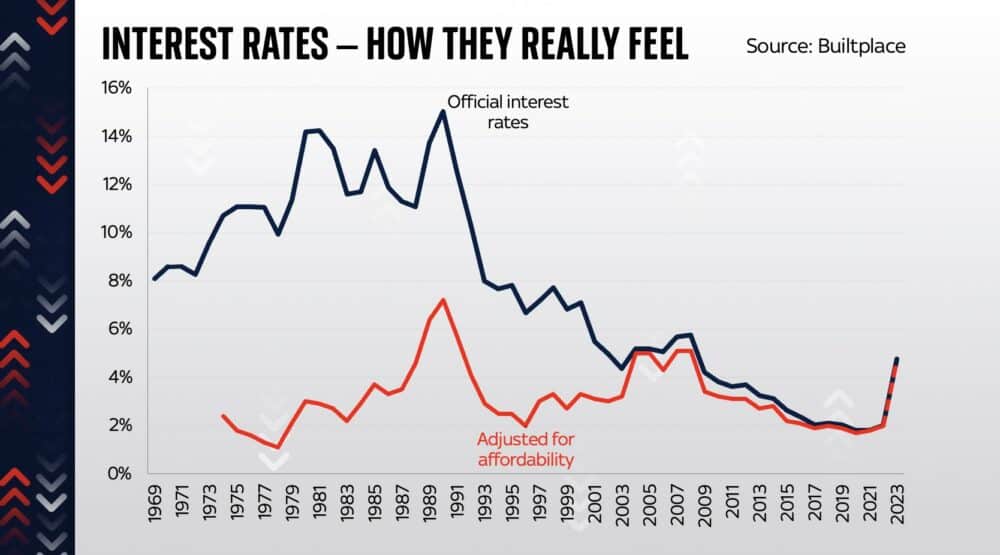

In one sense interest rates of 6% is not high by historical standards, but above inflation house price rises, mean that we are more sensitive to interest rate rises than ever before.

Adjusted for affordability, it will push rates up to those seen before the 2007 crisis and not that far off the 1990 house price crash.

House price falls cause recession

Whilst house prices are overvalued, expensive and causing difficulties for many first-time buyers. A sharp fall in house prices would destabilise the economy and likely push the economy into recession. Every big house price fall in recent decades has caused a recession because it is such an important metric for the UK economy. It is the biggest form of household wealth, and pushing homeowners into negative equity would reduce their ability to take part in equity withdrawal, and also significantly reduce consumer confidence. A combination of high inflation, falling real wages and higher interest rates would seriously put people under pressure to reduce spending.

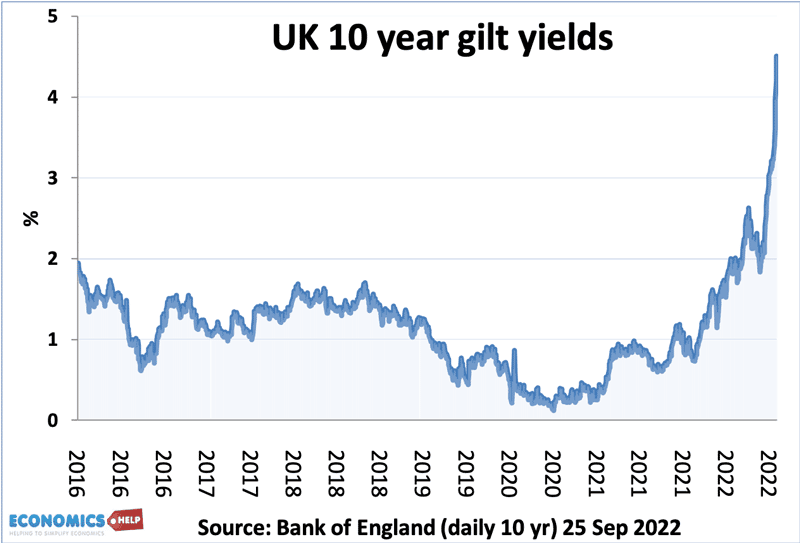

Rising bond yields

Before the rise in bond yields, the OBR expected UK debt interest payments to be in the region of £83bn or 2.5% of GDP. This is government spending that goes to holders of bond yields.

In April 2022, UK public sector net debt was £2,347.7 billion or around 95.7% of GDP)

- With average bond yields of around 3.75% the annual interest payment would be £88bn.

In 2023, if we have a £200bn increase in debt to £2,547 bn and average bond yields rise to 5%

- With average bond yields of 5%, the annual interest payment would be £127bn.

That would be an extra £40bn just on interest payments from average bond yields rising from 3.75 to 5%. Not This is not an exact forecast as we don’t know what will happen to bond yields, it just indicates how rising interest rates can eat into the government’s budget.

(I saw one forecast by Pantheon Macroeconomics that suggested that the UK’s debt interest bill would rise to £118 bn for the current financial year alone, but that was before bond yield surge. I would be very interested in OBR’s forecasts. Sir Charlie Bean – ex Bank of England chief economist told Channel 4 27 Sep, the bond yield rises since Friday will cost £20bn. A fifth of the education budget, 100% of the home office budget.)

Concern of permanently higher bond yields

The concern is that the loss of the UK’s reputation for low inflation and fiscal sustainability could lead to a permanently higher bond yield, like for example Italy in the 1980s. (Some analysts have called it the moron risk premium). Even if bond yields are slightly higher due to a decline in reputation, it will cost the UK government a fortune in debt interest payments. And there is a clear opportunity cost, if we spend more on interest payments, it is less to spend on health care, and education.

Spending cuts

One impact of large-scale tax cuts is that it will increase pressure on future governments to cut spending. In a recent editorial, the FT argued that if markets don’t readjust, the government should cut spending by £35bn. Even if a future government wanted to spend more (as they usually do) the legacy of higher debt interest payments would make it harder to finance ambitious spending schemes. For many years economists have been suggesting that with bond yields close to zero, governments should take advantage and increase public investment – even with borrowing. But, now there is high inflation and rising bond yields, this dynamic changed.

Unequal effect

The problem with interest rates is that there is an unequal effect. It is not the perfect policy instrument. Young people with loans and mortgages will be very hard hit financially. Older people who have paid off their mortgage will not be affected. The problem is that to achieve the desired result of protecting the Pound and reducing inflation, there are also equity issues with a particular cohort of younger people being more affected by the rising interest rates.

Interest rates not what the economy needs

An important feature about this interest rate rise, is that the Bank of England will raise rates reluctantly because the economic outlook is still quite grim, with businesses and households facing rising costs. Higher interest rates on top of this could create real problems for businesses and households. However, the interest rate increases is partly been driven by the need to shore up Sterling in the light of markets turning against UK assets. Also, it is a curious situation when the economy is been driven with the foot on the fiscal accelerator, but another foot on the monetary brake. It sends confusing signals to the economy and makes it harder to predict the outcome. Because of rising interest rates and lack of confidence, tax cuts received by firms and high-income households will likely save a high proportion of extra income, reducing point of fiscal expansion.

Evaluation

There will be some people who benefit from increasing interest rates. Notably savers, who might legitimately claim real interest rates have been negative for too long, meaning their savings have declined in value (inflation higher than interest rates). Rising rates will be good for those who savings, and will increase their disposable income.

thanks