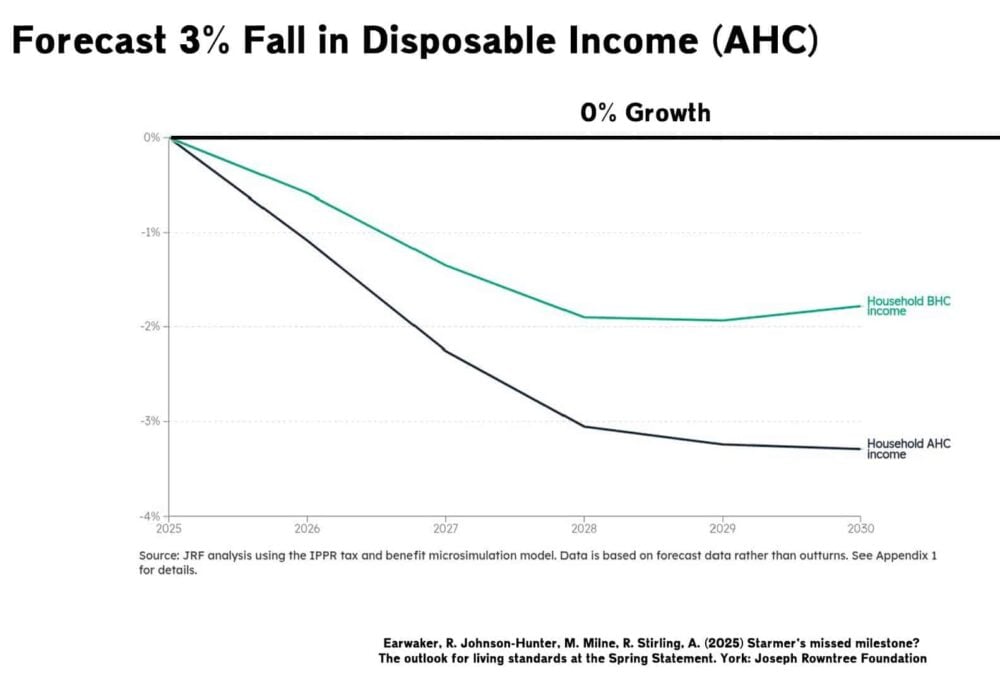

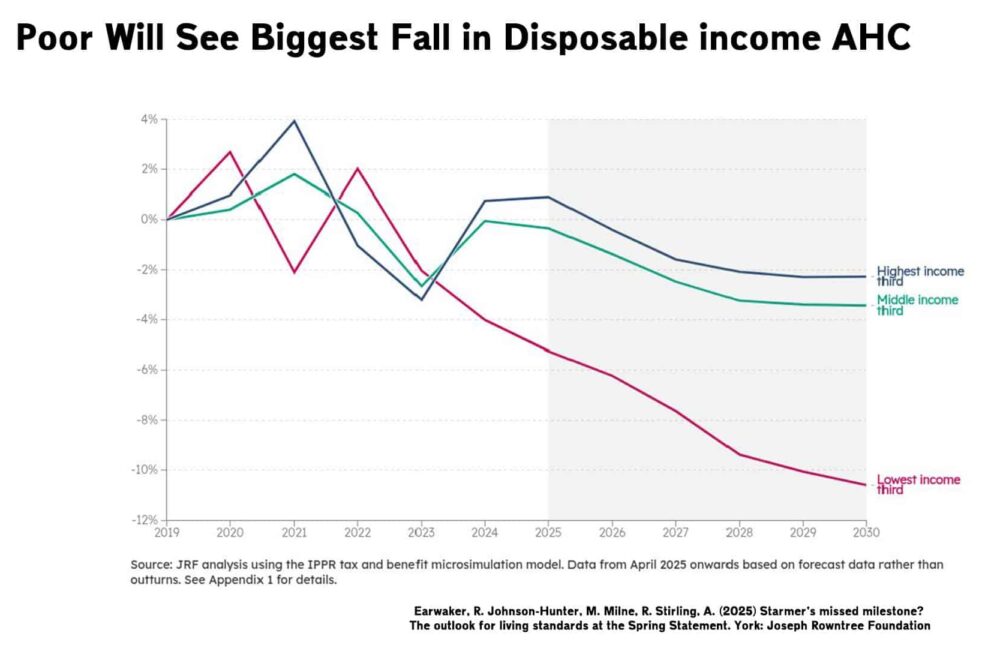

After 15 years of stagnating living standards, a new report suggests that after housing costs, real disposable income are likely to continue falling for the next five years. The decline will be felt by all income groups, but those on benefits, poorer households, and single parents will see the biggest decline.

The only group who will do marginally better are pensioner couples. The biggest reason for the decline in living standards is a continued period of very low economic growth, combined with higher taxes, higher housing costs and lower benefits. It means the average household could be over £1,400 worse off in 2030 compared to 2019.

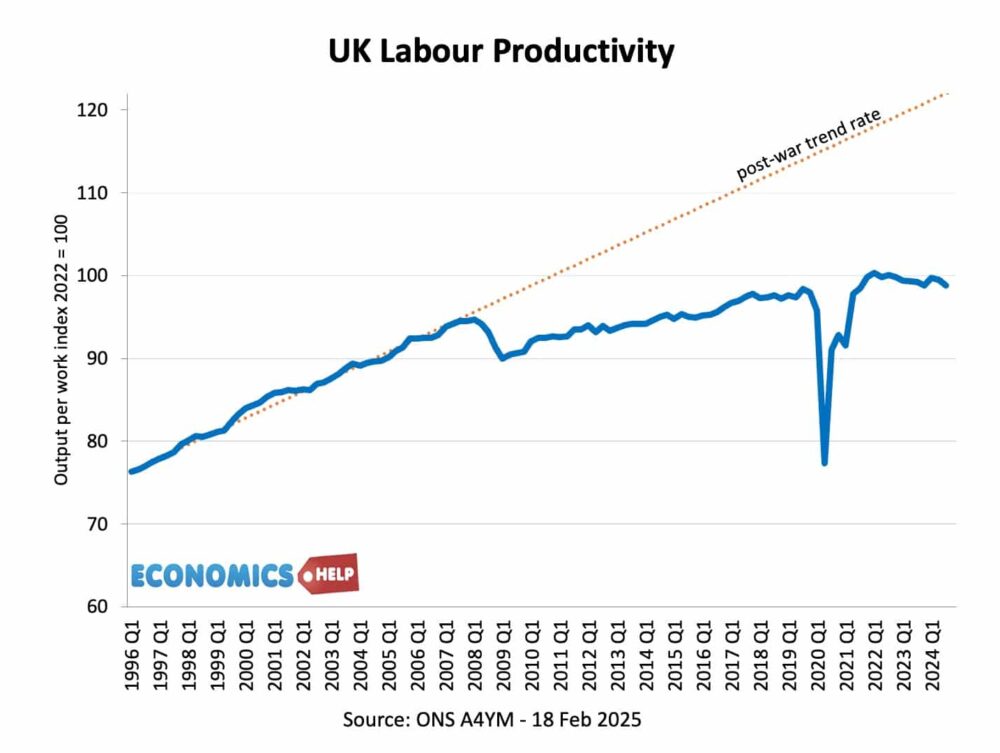

To put this into context, the post-war period saw several decades of average household incomes increasing, but since 2008, that growth has been broken. Meaning household incomes are £10,000 less than if past trends had continued. But, an actual decline in living standards on top of this would be a real problem for both households and general government finances.

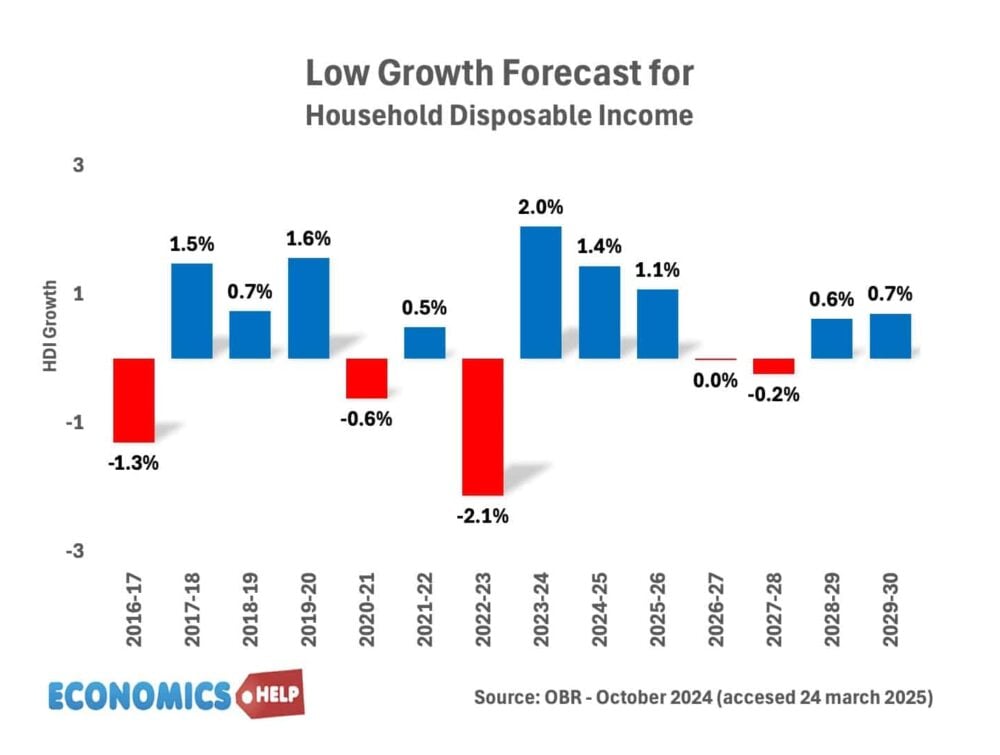

The OBR forecasts from October 2024 were slightly more optimistic for household income with very modest increases pencilled in for the end of the decade. But, since October, estimates for the economy have worsened with both higher interest rates, lower growth and higher rents. The OECD have recently downgraded forecasts for the UK economy and worryingly for the government, bond yields have risen to the highest level since the financial crisis. The UK now has one of the highest borrowing costs. This creates an unfortunate dynamic, meaning that high levels of debt require more interest payments. Debt interest payments are now the third largest component of UK government spending. It’s a real headache. In 2024, the new Labour government inherited one of the worst combination of high debt, high interest payments and low growth.

But, if anything, growth has deteriorated in past nine months, leading to higher borrowing costs and higher than expected levels of borrowing. It means the chancellor’s already small fiscal headroom has been eroded, giving another painful choice of spending cuts, higher taxes or more borrowing. But, in trying to meet fiscal targets, ironically the economy has been weakened. Firstly the planned rise in employers’ NI has led to lower levels of hiring. The Resolution Foundation suggests that the decline in employment is starting to resemble past recessions. Secondl,y benefit cuts will hit the spending power of households when confidence is already low. For the government,t there is a reluctance to borrow more as a temporary stop gap because, firstly, borrowing is now more expensive but secondly, long-term debt forecasts are pretty grim. An ageing population will cause welfare spending and health care to significantly increase in the coming years and that’s before things like higher defense spending and backlog of problems from the past decade of austerity. National Audit Office highlight £49bn backlog.

Global Downgrades

One reason for the downgrade in UK growth forecasts is the deterioration in global growth prospects. The new reality of Tariff wars and general uncertainty has seen Gold soar in value as levels of global uncertainty reach the highest level for decades. Whilst many countries face a similar challenging economic situation. The UK’s growth in incomes have been amongst the lowest amongst advanced economies in recent years.

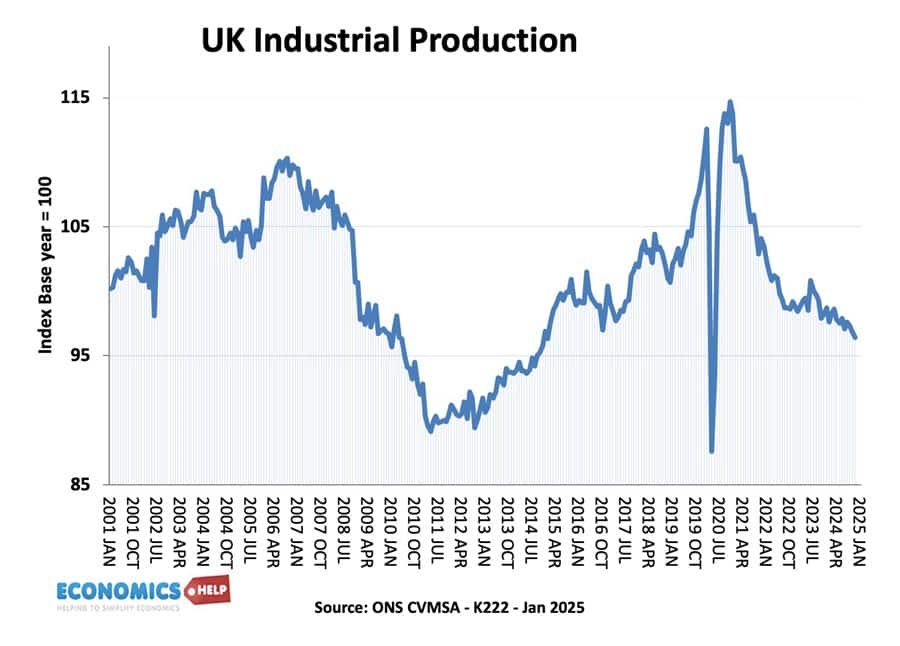

The UK economy is struggling in the industrial sector. Recent data shows some improvement in the service sector, but big falls in industrial production. One big problem for the UK economy is the relatively high price of electricity, this is hurting energy-intensive industries like the chemical industry. In fact, the UK economy is almost a story of two different parts – services increasing, industry decreasing. High energy prices also hurt households with energy prices rising faster than inflation and a significant drag on living standards.

Housing Market

Another weak part of the UK economy is the housing market, with high house prices and rapidly rising rents. Especially for those in the private rented sector, housing is taking a bigger share of income, snuffing out any gains in rising wages. Although high housing costs are a problem across the developed world, it is not unsolvable. Cities in the US with loose planning rules have seen big increase in supply and falling rents. Japan is an interesting case study for the UK – three decades of stagnant growth, something the UK could soon be emulating, but this stagnation in growth has been helped by the fact Japanese housing is relatively cheaper. London rents are over £2,000; in Tokyo, they are £1,300. Japan has very different planning rules, which sees houses being built in high-demand areas. Another contrast is that the UK housing market has seen added pressure from the growth in population, largely caused by high levels of net migration in recent years.

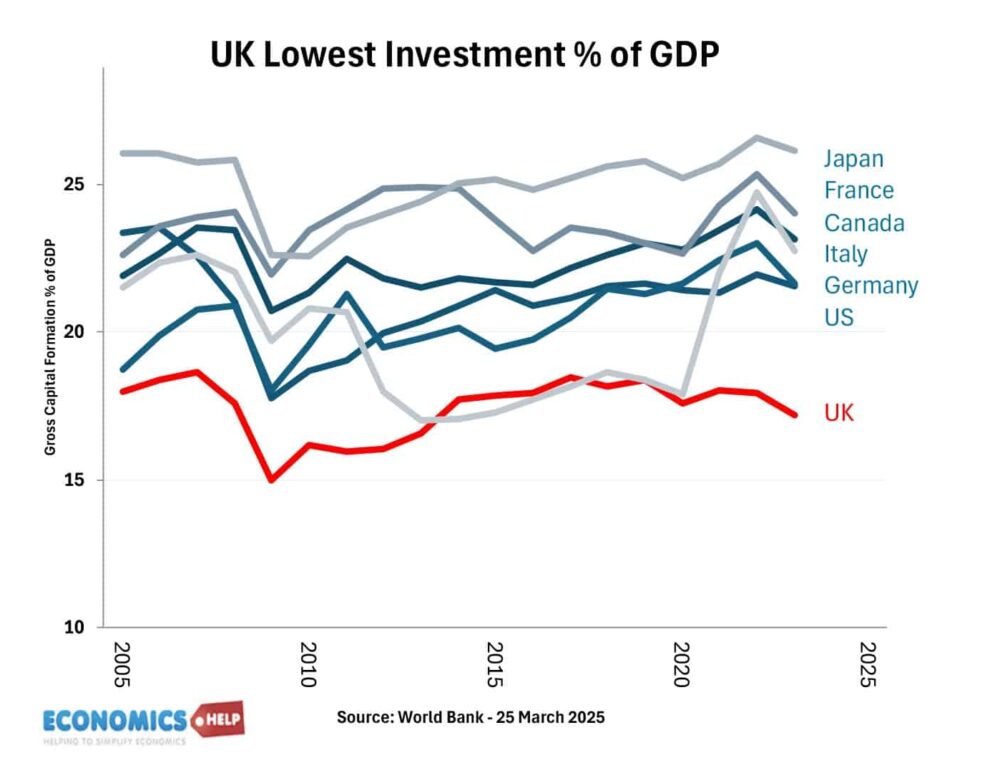

Another reason for low growth is low levels of investment – both public and private. UK investment is low for a variety of reasons. Planning restrictions have held back investment in housing and manufacturing. The Brexit shock of uncertainty and new more expensive trading relationships has hit business confidence. According to NIESR, the costs of Brexit have so far reduced GDP by around 2-3%, but by 2035, these costs could escale to 5-6% or £2,300 per capita. The OBR predict a smaller net loss of 4%. But, at least some of the future low-income growth is impacted by Brexit.

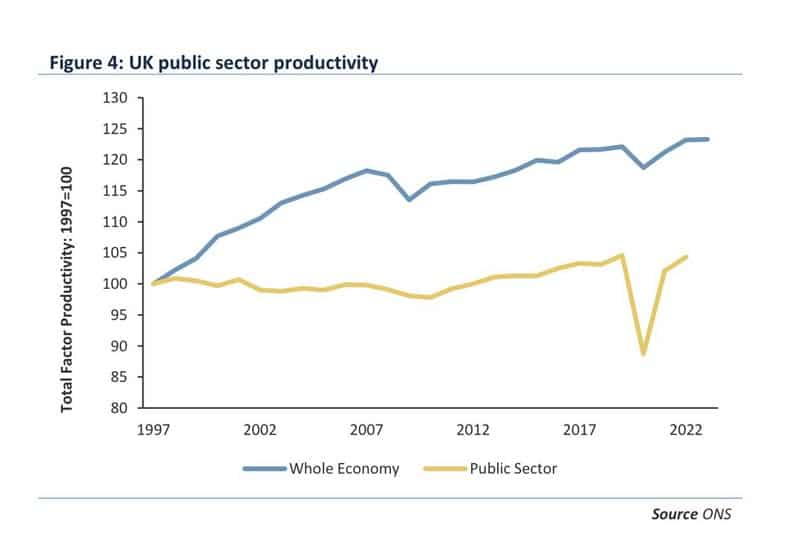

Apart from low investment, what else causes low productivity? Government spending as a share of GDP is rising, but the public sector has added stagnant productivity growth

This graph shows a stark contrast between the two sectors. Despite digitisation, public sector productivity is disappointingly absent. Also, it can be harder to increase productivity in a service sector-based economy, where labour costs take up a bigger share of inputs. It’s not just the UK, global productivity growth has slowed since the financial crash,and firms are still taking time to work out how to benefit from AI technology. In fact if you’re looking for a more optimistic take on the economy, some argue GDP is actually underestimating living standards and we are doing better than GDP suggests. The argument is that these days people spend 8 hours a day on an electronic screen, and a lot of this consumption is relatively cheap, if not free. Back in my day, a CD may cost £15, today you can more or less listen for free. According to statistics, that is a decline in GDP but we are still consuming the same music. But, there is another counterpoint to this technological nirvana view, and that is living standards are actually worse because of technology – addiction to smart phone is making us depressed, distracted and wasting our time. Maybe it’s a coincidence but the smartphone arrived just before the productivity slump.

Inactivity

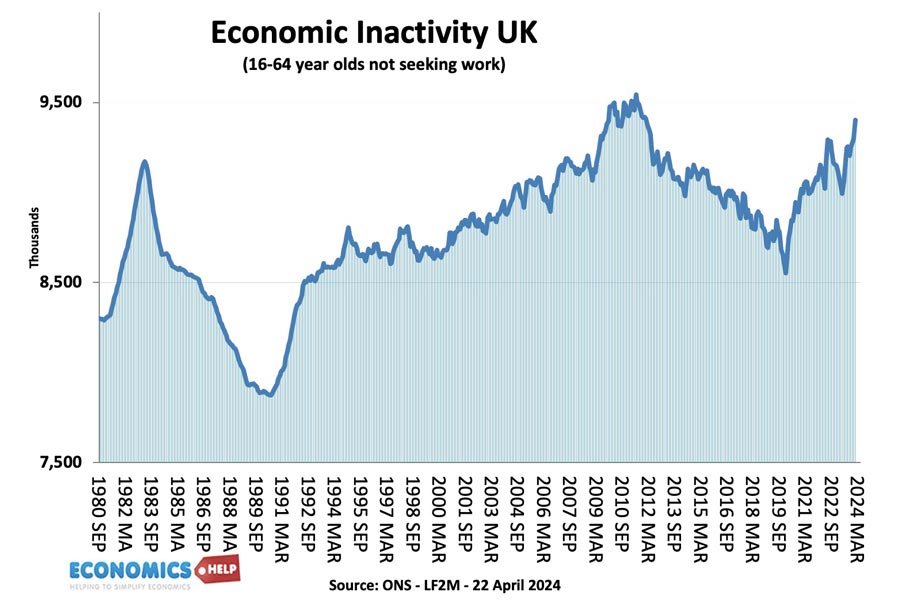

Anyway, that’s an interesting question for another day. Another big potentail cause of low growth is the rising rates of economic inactivity, especially amongst young people. Rising sickness is a big problem for the economy and households. In 2002, the UK had the lowest rate of inactivity in Europe, now it is the highest. Inactivity costs both the government, individuals and economy.

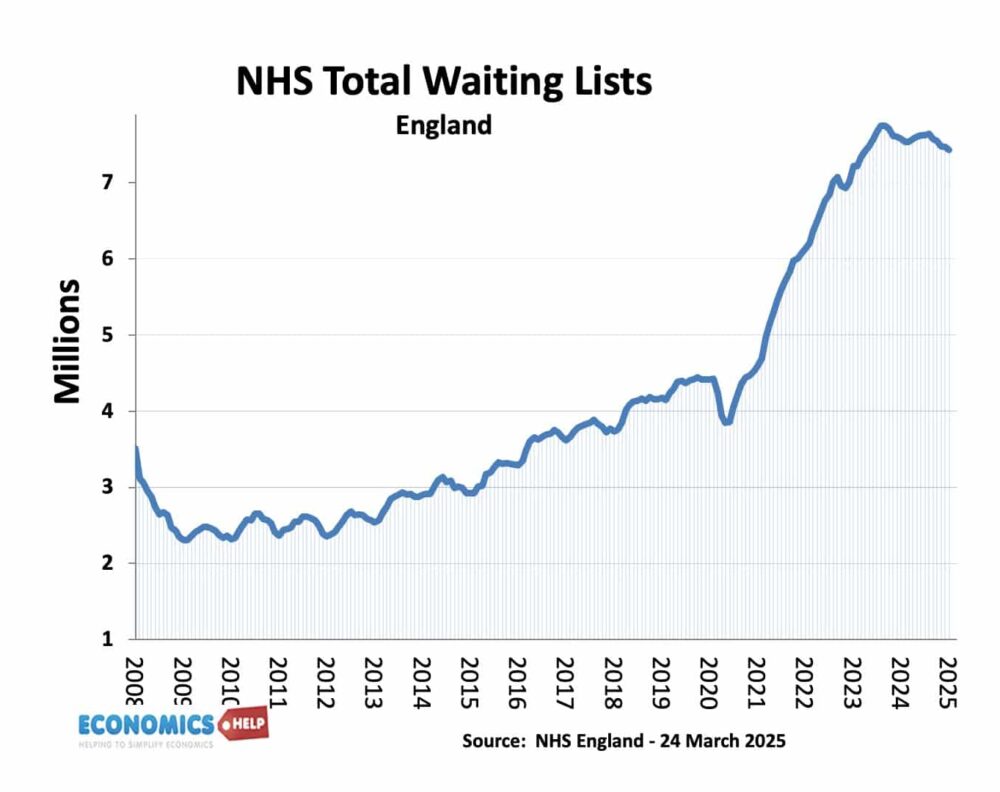

It’s not just future income which are important, but also state of public services. Stagnating incomes can be offset by rising quality of housing, health care, education and transport. But, unfortunately, there seems to be no easy cure for the state of public services. Despite higher spending, NHS waiting lists increased significantly in past decade. There are tentative signs of very slow decline in waiting lists, but it is from a high base.

More Optimism

That’s a pretty grim picture, but could these dire predictions of falling household income prove inaccurate? Economic forecasts certainly have a high probability of being wrong. Unfortunately, the recent decade has often seen economic forecasts be over-optimistic and the outcomes generally worse than OBR forecasts. The most worrying is the frequency with which the OBR has assumed a pick up in productivity for the UK economy only to be disappointed. If productivity continues the trend of the past five years, incomes may fall more than OBR predict.

But, still there is a way to paint a more optimistic picture. For all talk of falling household incomes. At least at the moment, wage growth is running at 6% a year. This is largely due to government increasing public sector pay, after many years of falling behind. This kind of pay growth won’t last. But, it is reminder that although higher taxes are depressing demand and job creation, they are offset by higher government spending. It’s not really an austerity budget, there is a small net stimulus effect. Although government will undoutedly miss its very optimistic house building targets, there is at least signs that relaxing planning rules will have a positive effect on increasing construction. Combined with slightly higher levels of public investment and more defense spending, the net effect will be some positive impacts on the economy. Further rises in the minimum wage will lead to higher incomes for those in low-paid industries.

Also, there is some evidence that a big problems for the UK is just very large levels of pessimism. Saving in the UK continue to grow to their highest level. This is both good news and bad news. It is good, households have a greater cushion of savings, which in theory they could spend. But, it reflects low confidence about the future of the economy. Whilst consumers hold back from spending, it will also mean firms hold back from investing.

What could be done to improve incomes in the next five years. Reverse NI hike and means testing winter fuel, uprate housing benefit and end two-child limit. To raise revenue, end the triple lock pension guarantee and impose tax on bank profits of quantitative easing, plus other potential. I would also want the Bank of England to halt its policy of reversing QE. We don’t need higher bond yields at the moment.

Sources

https://niesr.ac.uk/blog/five-years-economic-impact-brexit

https://obr.uk/forecasts-in-depth/the-economy-forecast/brexit-analysis/#assumptions

https://obr.uk/box/how-are-our-brexit-trade-forecast-assumptions-performing/

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2025/mar/06/uk-construction-sector-activity-plunges-pmi-report