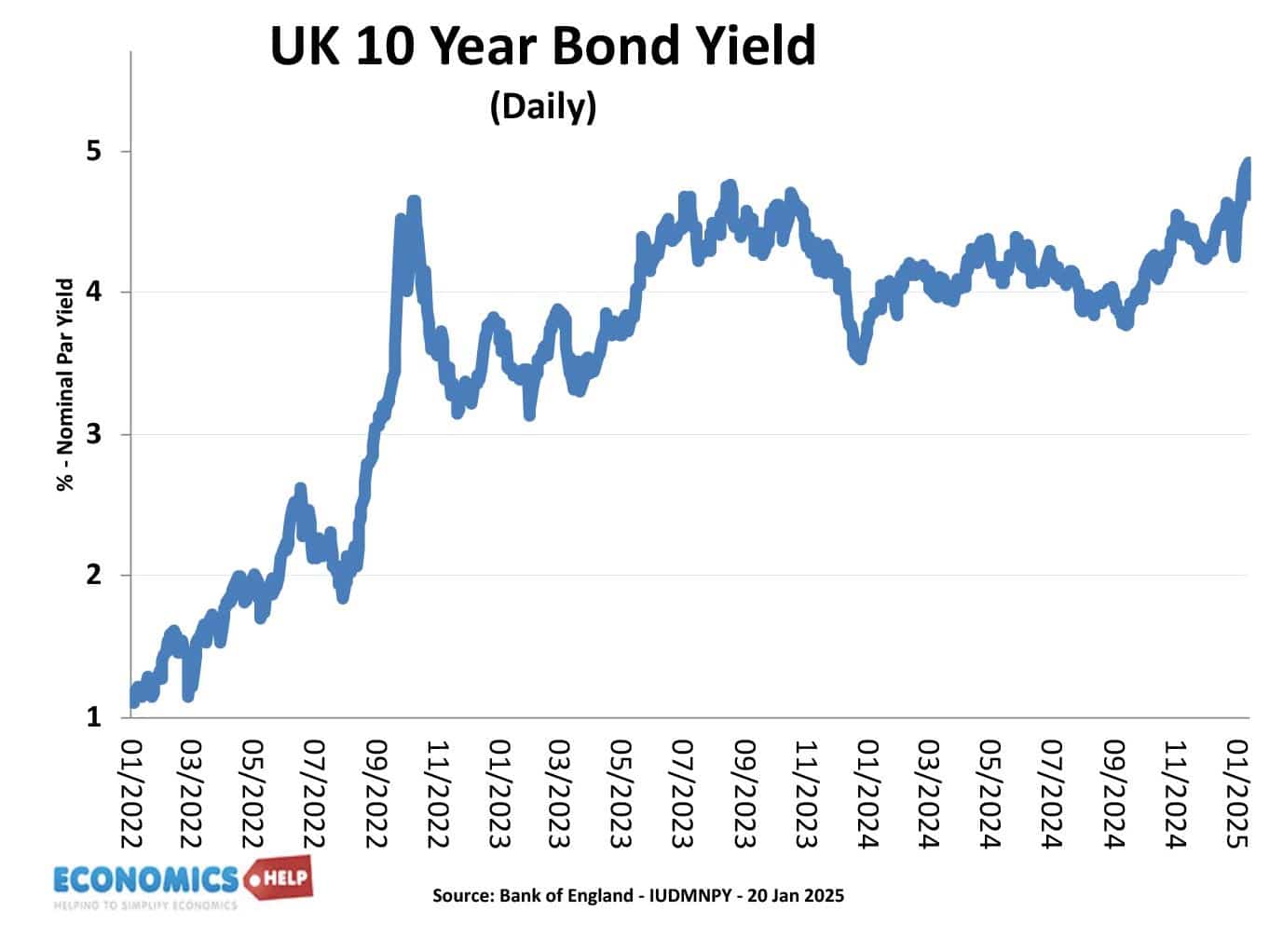

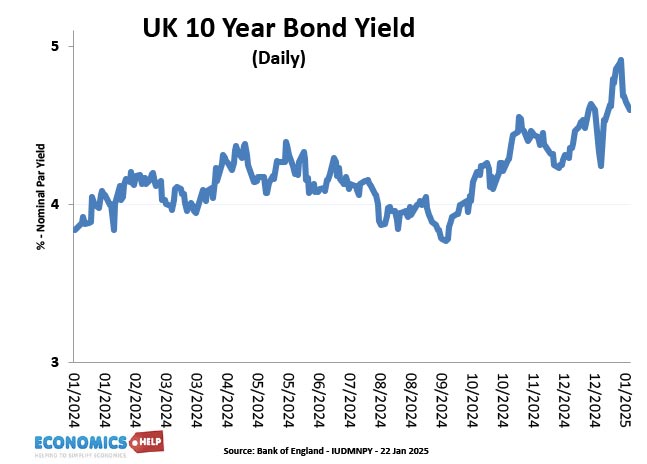

The start of 2025, saw UK bond yields soar to the highest level since 2008, causing the media to panic the UK was heading towards another debt crisis – worse than Lizz Truss, some papers rather hysterically claimed.

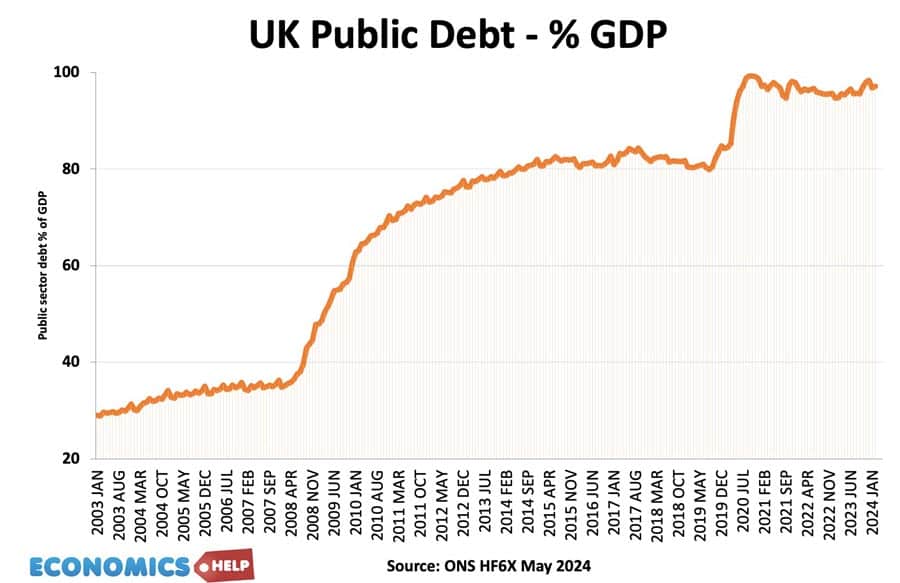

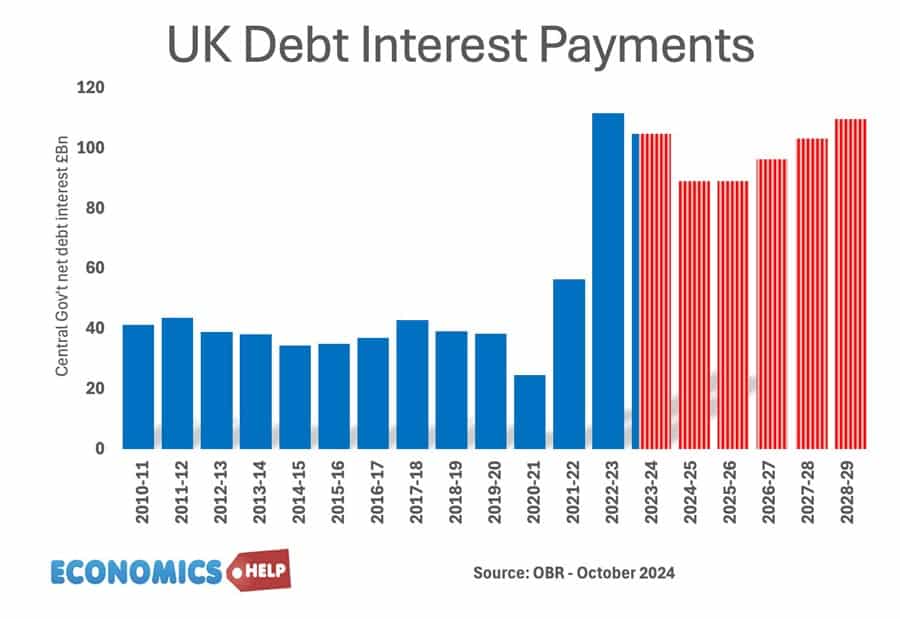

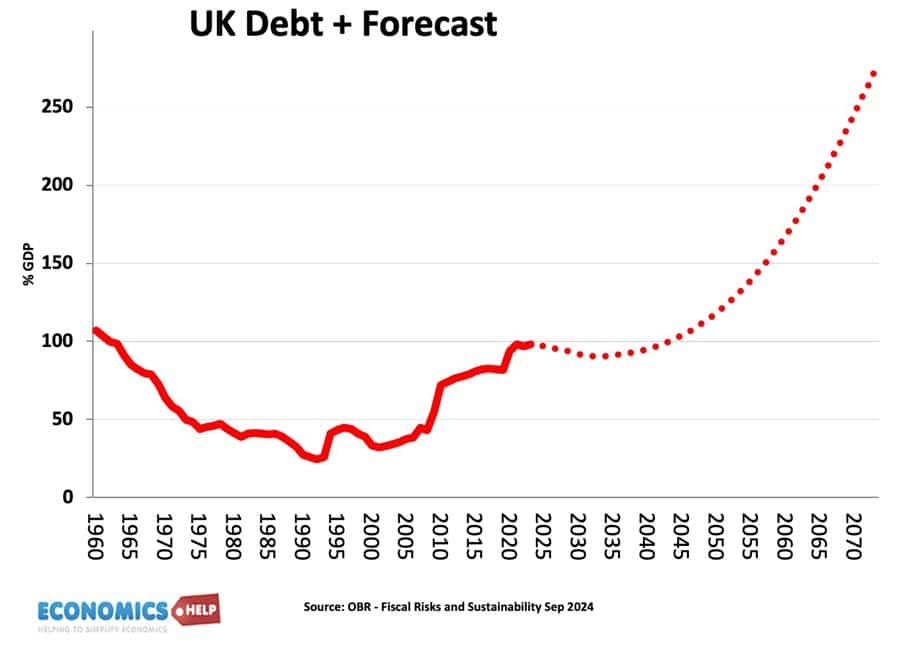

Since 2003, UK debt has risen from 30% to just under 100% of GDP, and with higher bond yields, the cost of debt interest payments has nearly doubled to over £100bn a year.

The UK has one of the most expensive borrowing costs among advanced economies. But, these short-term issues pale into insignificance when compared to the next 50 years, projections suggest government debt will continue to soar in the coming decades as an ageing population, falling birth rates and a shrinking working population is going to place a huge stress on UK government finances.

So does this mean the country is heading towards bankruptcy or are the debt fears exaggerated and misunderstood by the media?

Well, the media can often jump on short-term news and declare a debt crisis. I’m old enough to remember 2010 when the dominant media narrative was that deficits were too high, and if we didn’t immediately embrace austerity, bond yields would soar and the world would end kind of thing. Ironically, in 2010, debt was a relatively modest 55% of GDP. It’s now almost double.

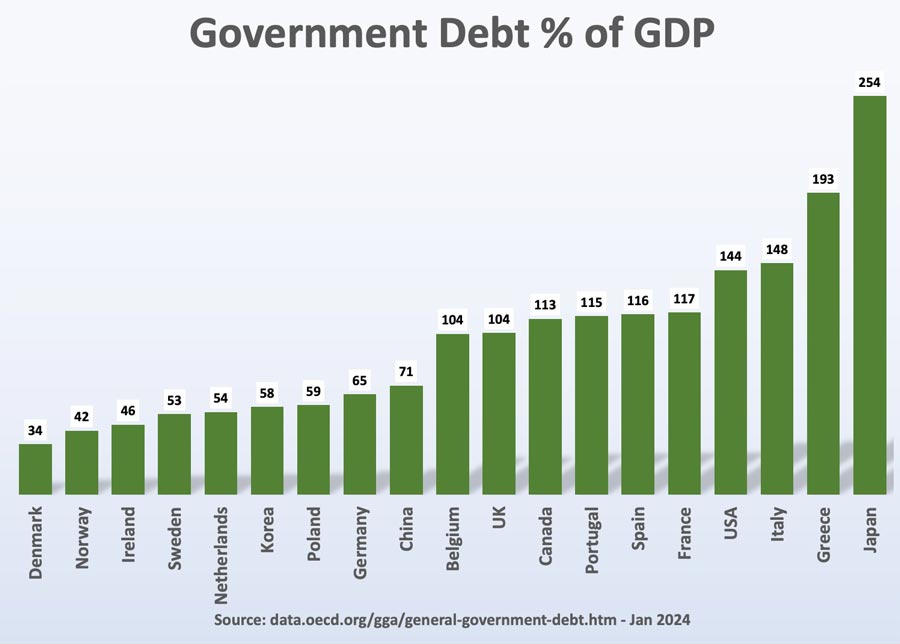

Firstly, it is always worth placing UK debt into a historical context. Since 1776, UK debt has averaged over 100%, and in fact has risen over 200% of GDP in the aftermath of the Napoleonic War and the Second World War. Even with very high levels of debt, the UK didn’t default but was actually able to reduce the debt burden over a few decades. Secondly, if we place UK debt in an international context, UK debt is high, but it is not uniquely high. Japan has debt of 254% of GDP. Italy 148%.

But, going back to the 1950 debt peak – some things were different. Firstly, some of debt was the government nationalising industries and gaining assets like the railways. The government also invested in rebuilding the economy after the war. It was also the start of the global post-war economic boom. A young, growing workforce helped the economy expand by over 2% a year. This rise in incomes and output led to higher tax revenues and falling debt as a share of GDP. At the very least, it shows that borrowing for investment does not have to be a constraint on growth.

Low Growth = Debt Headache

The problem for 2025 is that the UK, like many other European countries, has seen 14 years of very low growth, barely increasing GDP per capita. When the economy stagnates, tax revenues stagnate, but you need to keep increasing spending on health care to keep up with demand. The OBR are very pessimistic about future prospects for UK debt. Assuming no change in policy, spending commitments will soar because an ageing population will lead to higher pension spending and higher health care spending, but tax revenues won’t grow as much because we have less people working. Now this pessimistic scenario isn’t set in stone. If the government changes policies like say raising the retirement age, increasing the rate of VAT or ending pension triple lock, it could lead to a very different outcome where debt rises more slowly. However, will any government be able or willing to address, unpopulat long-term spending commitments? The current government lost a huge amount of support from means testing winter fuel allowance, yet, this deeply unpopular policy will save only around £1 billion a year, a proverbial drop in the ocean. The triple-lock pension guarantee has become a political article of faith, but it will be increasingly expensive and ensures pension spending will continue to grow, most likely faster than the rise in tax revenues. This is a real problem a political incentive to avoid difficult decisions like social care.

Who Owns UK Debt?

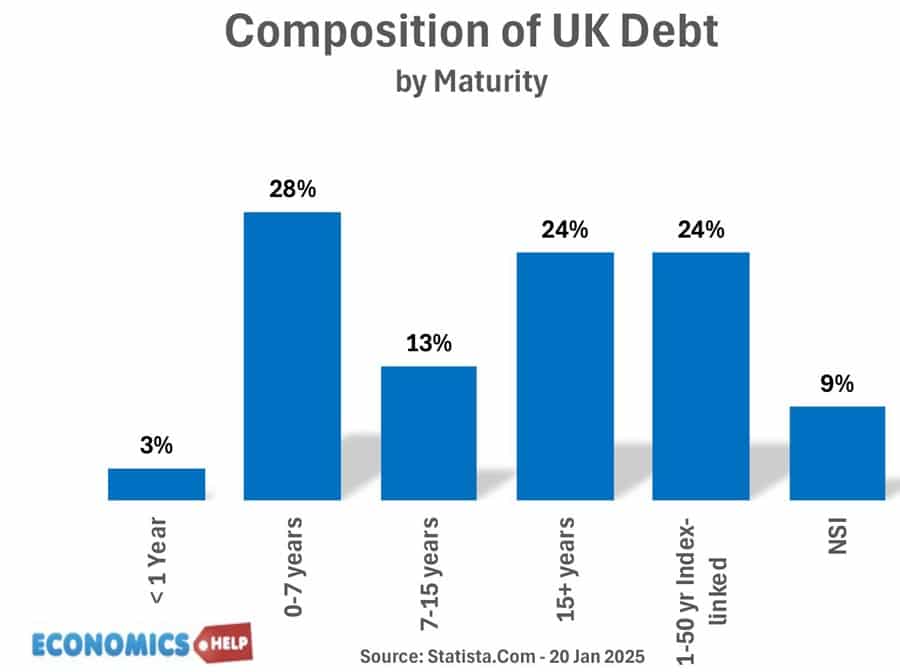

Debt by Maturity

UK has relatively high level of long-dated debt (over 7 years)

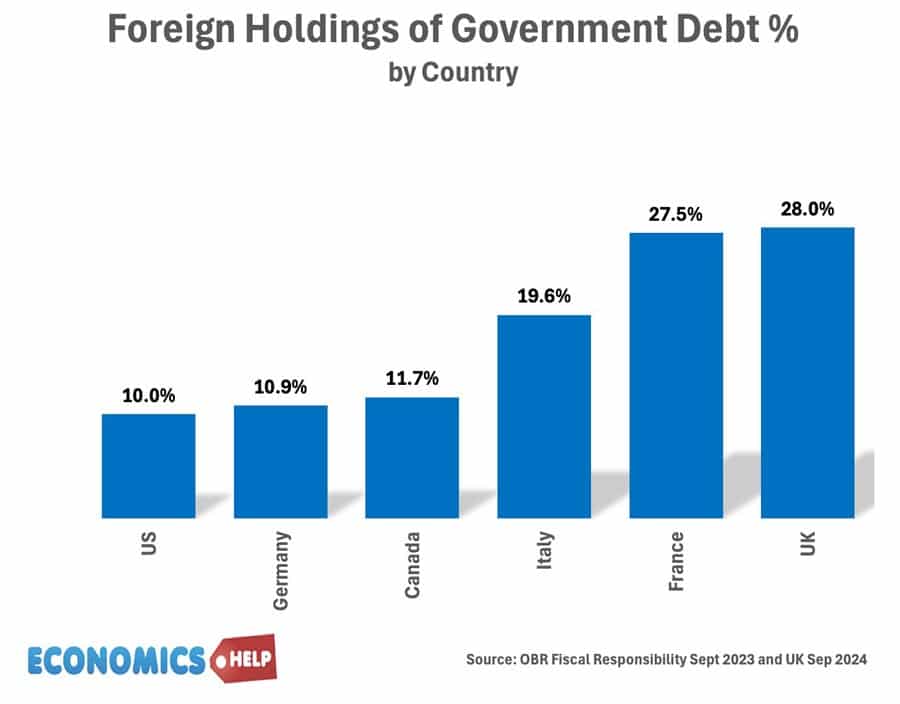

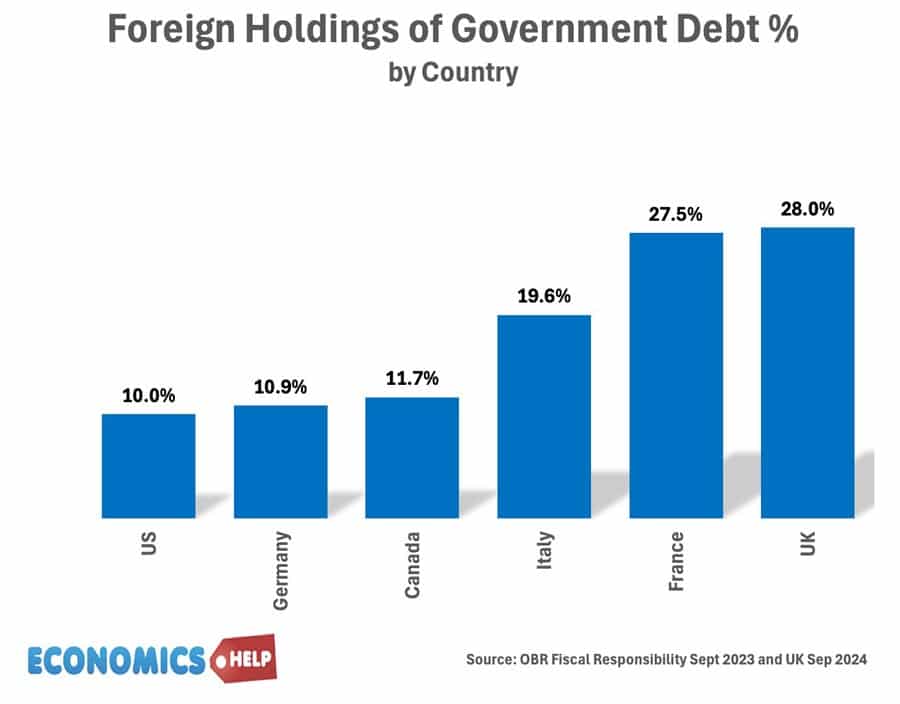

Now, what do we mean by national debt? Because the term is something of a misnomer because it is not actually the amount the UK owes to other countries. Around 72% of UK government debt is held by UK banks, investment trusts, pension funds and the Bank of England. Around 28% of UK debt is held by overseas investors. This is actually one of the highest rates in the world. Japan and the US only have around 10% of their debt held overseas. And you could argue high foreign ownership of UK debt makes the UK situation more vulnerable. Overseas investors have less attachment to UK. Any weakness in sterling or UK economy could see investors move elsewhere. But, on the other hand you could argue international investors have the same information as domestic investors and I doubt many UK citizen are buying UK debt out of patriotic duty to help the government, like perhaps during the World Wars.

Debt as Household Budget

Mrs Thatcher famously referred to government borrowing like a household budget. Never spend more than you receive, and she used this to justify spending controls in the 1980s. It was the logic behind austerity for the 2010s. If you view government finances in this context, debt is out of control. But, is this analogy actually correct? Unlike a household, the government can finance its own debt. Secondly, within the UK some of the wealthy members of the household have surplus savings, think of a rich uncle who has retired, whilst others need help buying a house or going to university.

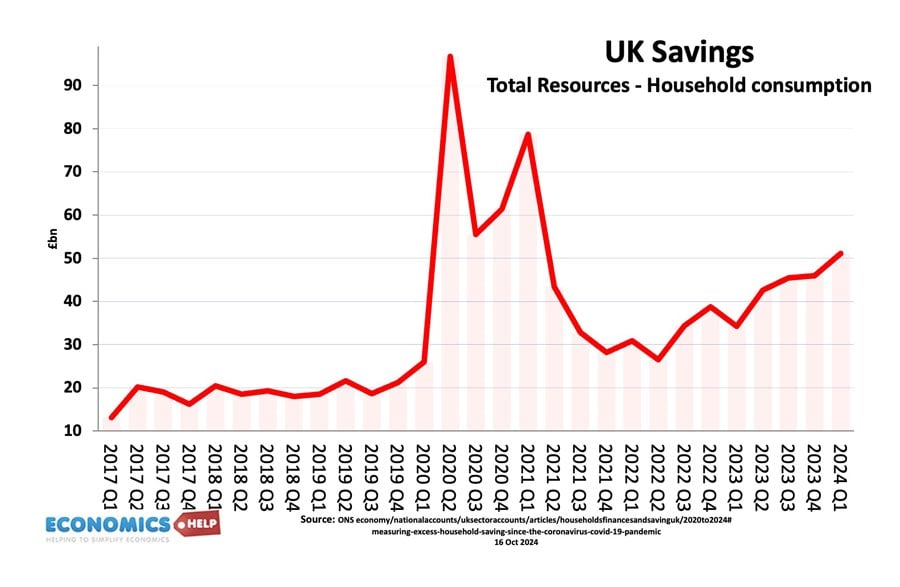

Debt and Savings

UK government debt often mirrors private sector saving. When the private sector saves more, the government can use this saving to spend in the economy. In recent years, the level of private saving has increased significantly. When saving increases – where does it go – a lot will be invested in government bonds. Higher saving reflects higher levels of private pensions and a lack of confidence to spend and invest. Government debt has to be seen in relation to private savings. If the private savings fell and the government borrowed more from overseas, this is often a trigger than government debt is more vulnerable to default and serious problems. This is not happening in the UK, at least not in the near future. One way to see government debt is that it is moving money from rich people with excess savings the kind who buy bonds to poorer people with less.

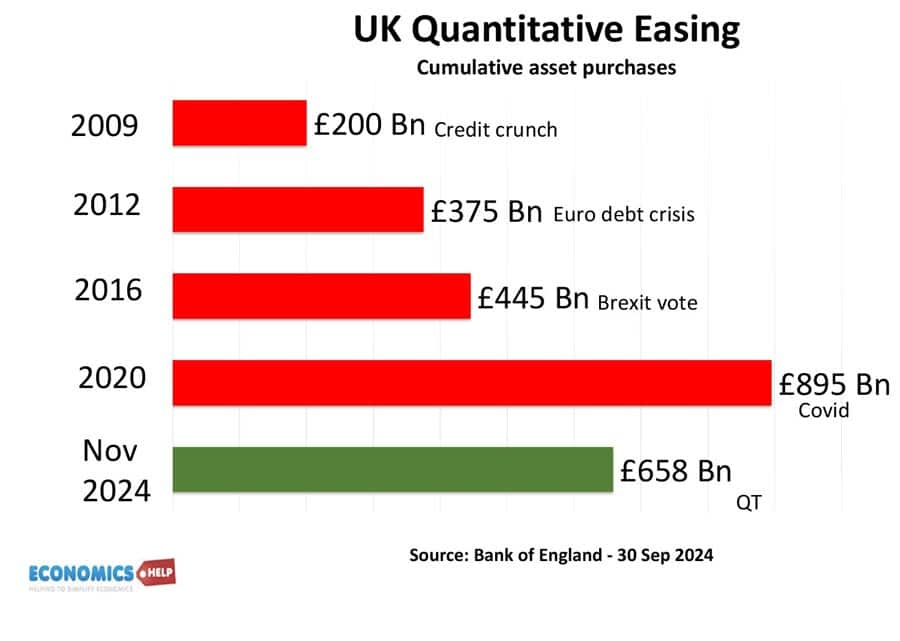

Quantitative Easing

In recent years, the Bank of England have created money to buy bonds from the government. This reached £900 bn in 2021 or nearly 30% of UK debt. In the past two years, the Bank of England have aggressively reversed quantitative easing, selling bonds back on to the market. It means in the coming months, the UK will see £300bn of bond sales – a record. The Bank of England’s reversal of QE is definitely making it harder for UK in 2025, and could be a factor behind UK’s relatively higher bond yields. Arguably given the state of the economy, it would be better to wait. But, it does raise interesting points.

Firstly, it seems a strange definition of debt when the Bank of England owned by the government is buying bonds. In effect, the UK government owes a debt to itself. Secondly, if the UK ever has liquidity problems, the Bank of England can always restart some form of quantitative easing to buy up surplus bonds and reduce bond yields. This is touching on modern monetary theory. The concept is that with an independent currency, a central Bank can always finance government spending directly, through creating money electronically. QE happened in 2009, 2014, 2016 and 2022. It was one reason why government bond yields were so low in the 2010s, making it very cheap for last Conservative government to borrow. Now, increasing the money supply is great when inflation is low. But, doesn’t printing money to finance government debt lead to runaway inflation? Yes, it certainly can. The examples of Weimer Germany in the 1920s and Argentina in recent history, show that printing money to fund debt can create a real crisis of inflation, that’s just a different kind of default. It happened to a limited extent in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when inflation was higher than expected.

But Quantitative easing is actually technically different to printing money. In the 2010s, QE had very little impact on UK inflation despite the scale of bond buying. Even in 2022, the inflation was mainly due to covid supply constraints and oil prices rather than QE. Government’s are generally reluctant to undertake unorthodox monetary policy to fund investment. But, if growth and inflation is low, it can be done. However, increasing the money supply to fund all debt is not quite the magic money tree. Any increase in money supply to fund government spending is ultimately limited by inflation and the balance of payments. Creating money can deal with liquidity constraints and shortage of demand but doesn’t directly increase productive capacity and productivity. Creating money doesn’t create actualy nurses and workers. It’s not a solution to ageing population and massive increase in demand for social services.

It’s not just about an ageing population. Future budgetary pressures mean there is also a need to invest in new technologies like renewable energies, deal with impact of climate change, such as increased flooding. There is also pressure to increase military spending as a share of GDP. This wouldn’t matter if the economy was growing but it isn’t.

It is true that bond yields have risen in the past three years. But, this isn’t necessarily a harbinger of crisis. Bond yields can be misleading to an imminent debt crisis. US bonds have risen because of expectations of high economic growth. When growth increases, investors buy shares, sell bonds and bond yields rise. Though high UK bond yields hardly reflect optimisim over strong economic growth. High bond yields in the UK seem to reflect expectations of higher real interest rates – perhaps related to an overly cautious Bank of England keeping interest rates high. The fall in inflation in December was very welcome, as it makes interest rates cuts more likely in 2025. Lower inflation and suddenly borrowing can become cheaper.

So in conclusion is the UK bankrupt. No? The government can borrow a lot of money, especially when you have a Central Bank who can create money and the private sector has high levels of savings. Compared to the 1950s, UK debt is much lower. However, that doesn’t mean there is not reasonable grounds for concern. The underlying structure of the economy is different, growth rates have become much lower and any future government faces an unwelcome combination of higher demand for services, but falling tax revenues. Yet, at the same time, there is very little political bandwidth for deciding how to deal with projected rises in government spending. Then on top of that we live in an era of uncertainty, shocks like 2009 crash, Covid and the Ukraine war, can easily add another 10-20% onto debt levels. It’s not reason to panic. Governments should focus on people rather than bond markets, but 2025 could easily bring unexepected shocks and this video looks at prospect for a financial crash in coming year.

Related

External Links

“and this video looks at prospect for a financial crash in coming year.”

Where is the video please?