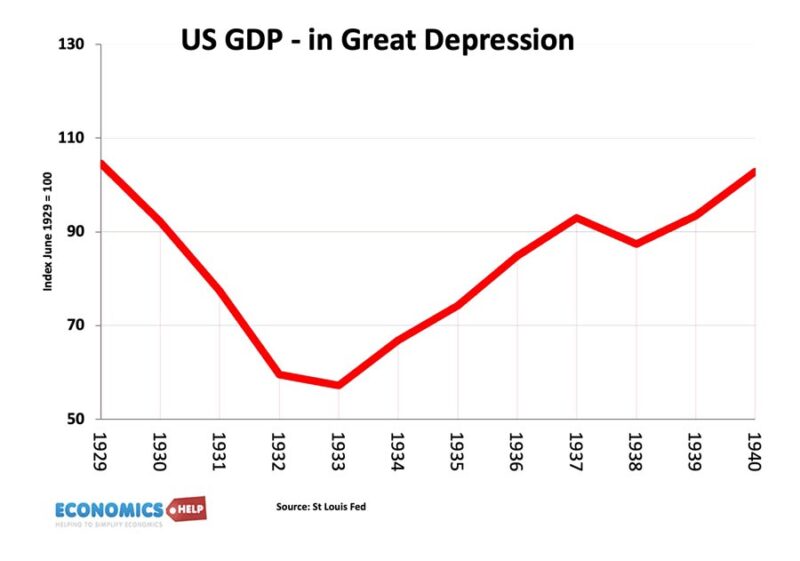

In 1930, the US economy entered a deep recession and President Hoover responded by passing the Smoot Hawley tariff bill which saw average US tariffs almost double. The aim was to help US manufacturers from foreign competition. But, the bill was a disaster, import prices rose and predictably other countries retaliated to US tariffs, it was a major factor in a disastrous 67% decline in global trade.

The next year in 1931, the US economy fell off a cliff declining a record 13%. There were many other factors at play, but tariffs definitely worsened and prolonged the great depression. Ultimately US business and consumers lost out from the trade war. Countries retreated into isolationism. Unemployment in Germany soared to 6 million. It didn’t end well.

Benefits of Free Trade

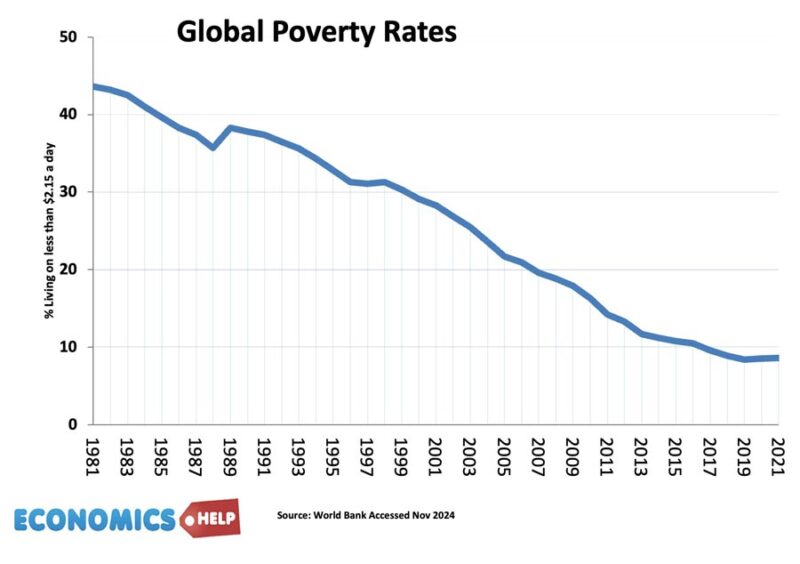

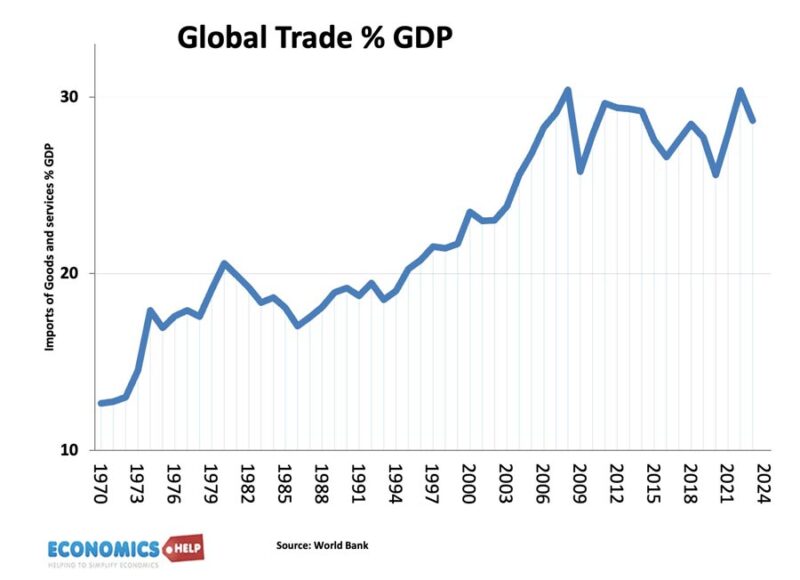

After the war, there was a steady decline in tariffs, global trade rose and economic growth lifted many developing economies out of poverty. It is fashionable to say free trade and higher GDP doesn’t help anybody. But, the past few decades have seen a remarkable decline in global poverty rates. This is a good news story. Trade is imperfect, but it has helped lift many out of poverty, especially in Asia.

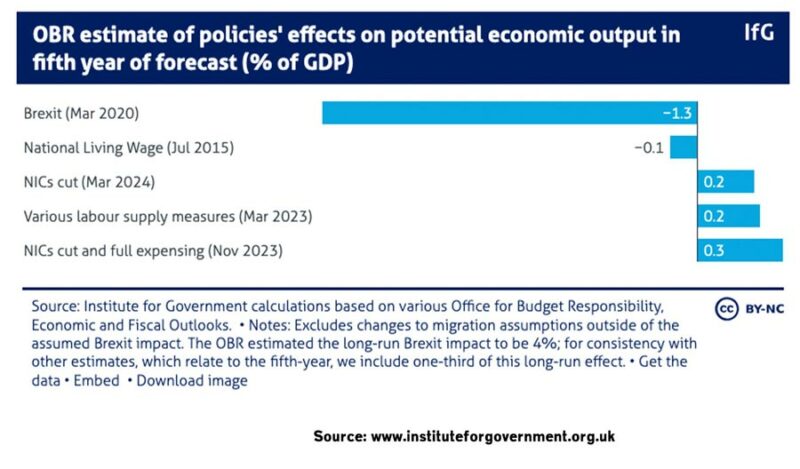

In 2016, the UK was one of the most open economies, relying on trade for a relatively high share of GDP. But Brexit saw the return of tariffs and custom barriers to the UK’s main trading partner. It is reduced both export growth to Europe and made it more difficult to import. At this point, I have to admit a vested interest. I have small business selling books to Europe. Recentlhy I had an order for seven books from Denmark. Before, Brexit, the shipping costs would be €21. Now if I pay custom duties in advance, the cost is €99 – 55% increase in costs. It made the order unprofitable, so it didn’t go through. I lost a sale, a Danish customer missed out. No body has benefitted from these tariffs. Hidden away in the recent UK budget, the OBR has modelled the impact of various policy changes on economic growth.

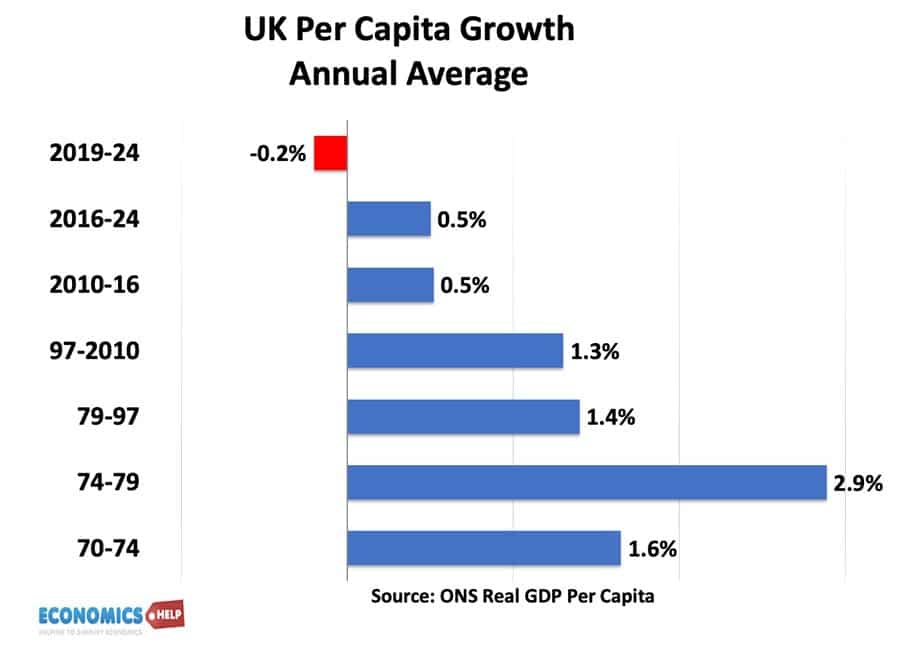

The elephant in the room is the impact of Brexit which is estimated to reduce GDP by 4% and that is one of the more conservative estimate. You might say who cares about 4% GDP growth, it’s not that bad. But, since 2019, UK GDP per capita has fallen 0.4%. The UK can’t afford a trade war to drag down grown and tax revenue.

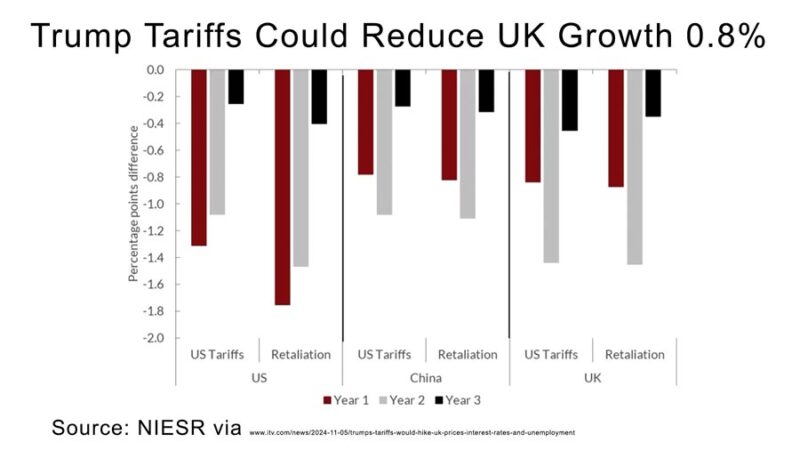

But, Brexit is just the start, if Trump’s tariffs are implemented, it could lead to economic shock of lower growth, higher prices and unemployment. 0.8% lower growth in the first year. Interestingly tariffs will hit the US even more.

Tariffs

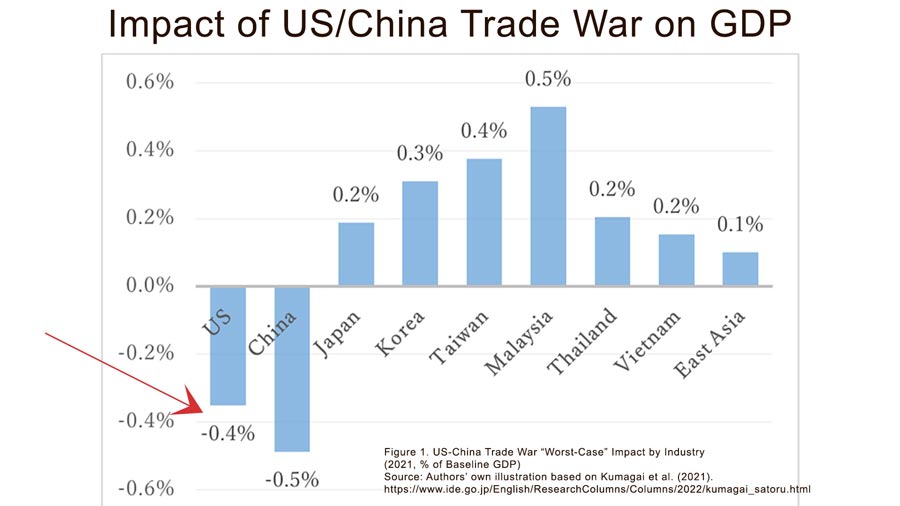

Now at this point, you might correctly point out – both Trump and Biden have placed tariffs on imports and the US economy has continued to do well. This is true. So far the tariffs have been relatively low and sparodic. Average tariff rates are still low historically. One study estimated the impact of Trump tariffs was to reduce GDP by 0.4% – in other words no-one will really notice. Even the impact of Brexit is not clearly visibile. It is more of a slow puncture than dramatic event. However, if we take Trump’s tariff proposals at face value, it could lead to unprecedented rise in tariffs to a level which will really be noticeable and have a big economic effect. Customers will notice this kind of higher tariffs.

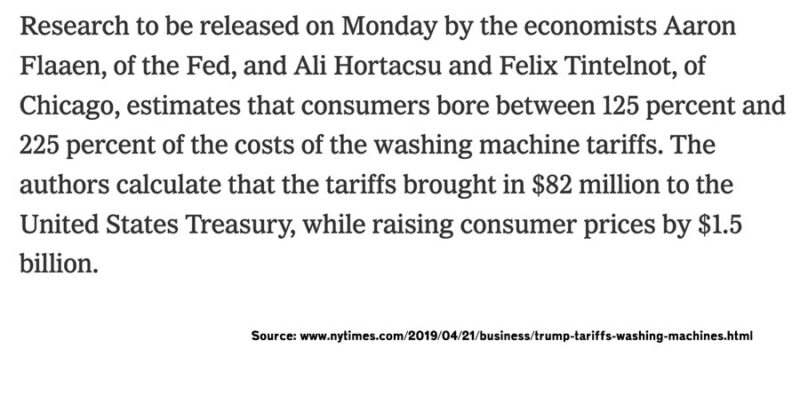

Trump has said that tariffs will be paid for by foreign countries, but that is not how tariffs work. In 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on foreign washing machines, tariffs started at 20% and rose to 50%. Research suggests consumers bore the brunt of higher prices. In fact producers took advantage of rising prices to charge higher prices for related goods like driers. On the positive side, the US treasury gained $82 million and US manufacturers saw rising demand, leading to 1,800 new jobs. However, the average cost of each job was an estimated $817,000 per job. It would be cheaper to pay someone to push paper clips around.

Hidden Costs Tariffs

However, the big mistake with tariffs is to think that is the end of the story, there are many hidden costs. Firstly, if consumers spend 20% more on washing machines, they have less disposable income to buy other goods and services. They will eat out less often causing restaurants to lose business. But, also, tariffs inevitably lead to retaliation. China responded to US tariffs by putting tariffs on US soybean exports. US farmers were unhappy with a decline in sales. The government responded by offering subsidy to farmers. But, this subsidy to deal with effect of trade war is ultimately paid by the tax payer. That’s the problem with trade wars, they escalate.

When tariffs are relatively small and isolated, the economy can shrug it off. But, if it is wide ranging, then the impact will be greater. Given relative strength of US economy, they may be able to brush off the impact of trade war more than saw relatively weaker European economies. Germany and the UK would be particularly vulnerable to a trade war because of high share of exports and also current economic weaknes. A hit to exports and consumer spending power could tip a weak economy into recession. But, when growth is slowed, governments and business can start making decisions which create a negative multiplier effect. True the US economy is impressive at the moment, but it has been maintained by low savings and high spending. A kind of cost-push inflation shock from tariffs could be exactly the kind of trigger to hold back on spending, then growth slows and investment falls too.

Can tariffs ever be good?

There are instances when tariffs can be justified. If a country is artifically reducing prices of goods through government subsidies this is classed as unfair competition, and a tariff to compensate for this effect is desirable. The problem the world has is that Chinese firms have received extensive state subidies, which have enabled them to flood the world with cheap steel and other goods. This is worrying because artificially low prices can push western firms out of business – not because they are inefficient but because of artificial competition, but if China do dominate then China has a monopoly in steel and in future can raise prices. Therefore, tariffs to deal directly with this can be desirable. The difficulty is knowing exactly how much China’s competitiveness is artificial and how much is just making cheaper cars. If you look at exports of high tech goods, China is coming to dominated. By 2030 an estimated 50% of manufacturing is expected to be in China.

Due to political sensitivities, there are concerns about relying on key components from unreliable partners. Free trade with Russia wasn’t such a good idea when you rely on gas to power industry.

For developing economies, their current economy may be stuck in producing primary products which offer little hope for economic development and growth. There is strong argument to allow tariffs to enable their economy to diversify and develop.

What about the argument that NAFTA and free trade caused job losses in US manufacturing and accelerated regional decline. Yes, the speed of manufacturing decline caused problems. But tariffs can’t necessarily bring back the jobs and prosperity. Biden’s new Green deal did actually saw a big surge in manufacturing investment, but relatively few jobs. The future of manufacting is automation. China’s surge in manufacturing exports is because of better automation. Jobs in manufacturing are never going to be like the 1960s. But, in the current situation a sharp rise in tariffs will hit consumer living standards, and consumer spending power. Business in Britain will suffer to some extent from the Brexit custom duties. But, they are still relatively mild, if we see a massive increase in tariffs across the world, everyone will be the loser.

Related