It was one of the biggest budgets in decades – Higher tax, higher spending, and more borrowing. Rachel’s Reeves hopes it will boost economic growth, avoid austerity and restore public services. But it is a gamble because if it fails to increase growth the UK will need even more tax rises or spending cuts just before next election.

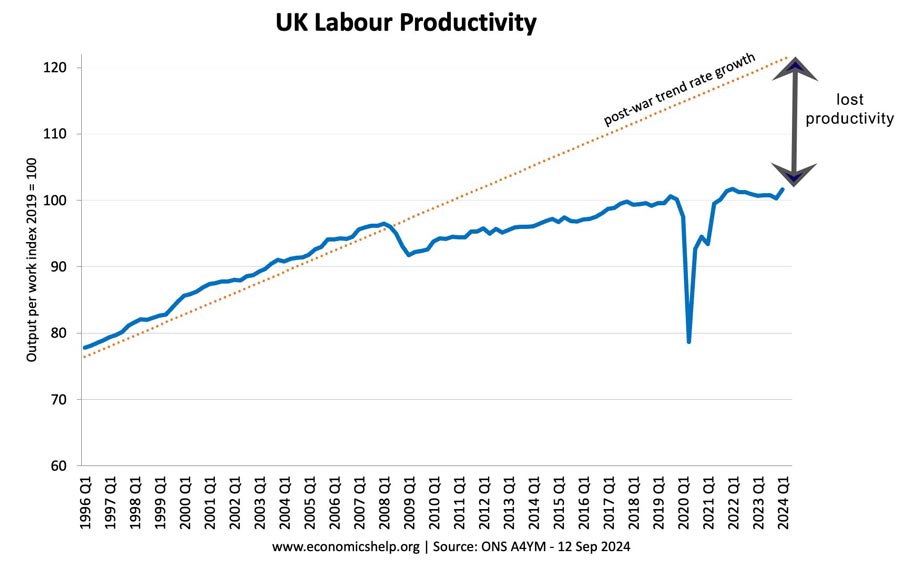

The backdrop to this budget is 14 years of economic stagnation, lost productivity growth which means lost tax revenue and living standards in decline. There was much talk of a £ 20 billion black hole, but this is misleading, it is much worse than that. Many public services, starved of funds have been running on empty, leading to over-flowing prisons, record health waiting lists and a shortage of affordable housing. It’s an old story, but it doesn’t magically go away just because you have a new government. In 2012, the UK was paying just £43 billion a year on debt interest payments. This year, it will be over £120 billion – a result of higher debt, but also higher interest rates. If we look at the rise in government spending over the next decade, nearly 33% will be due to higher spending on debt interest payments, no wonder there were nervous glances at the gilt market. There was no Liz Truss moment, but as we shall see it wasn’t without some glitches.

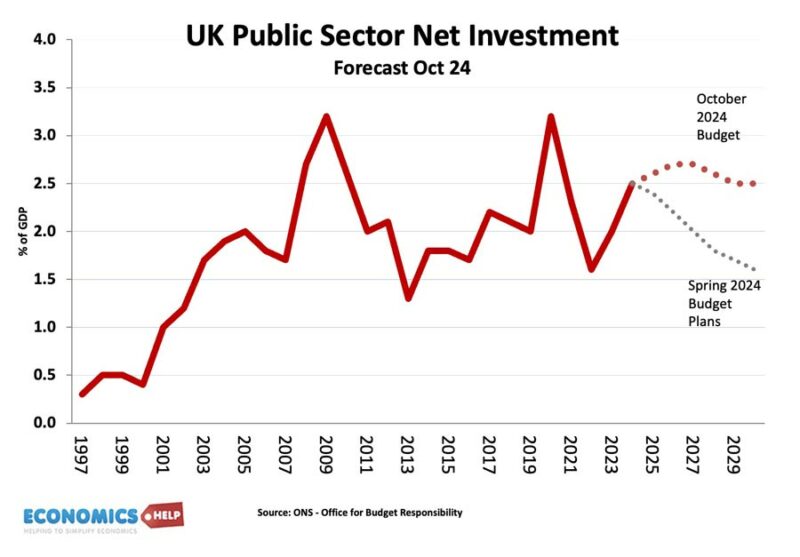

On the positive side, the government have announced an extra £66 billion of public investment over the next parliament. Under the last government, public investment was set to fall, now the country will see more investment in housing, transport and schools and public investment maintained at a more positive level. There was a change in debt rules to allow assets to be included. The IMF generally welcomed the move. One issue with public investment is that the benefits come in the long run, i.e. next parliament. This is why governments seeking short-term boosts in popularity tend to cut public investment, creating a cycle of short-termism. Public investment is no magic bullet, there’s no guarantee it will even be well-spent. but it is at least an effort to change the fortunes of the economy.

Tax Rises

Benefits in 10 years time are all very well, but in the short-term most UK citizens will be seeing the impact of the largest tax rise in decades. An extra £40 billion. After tying themselves in knots promising not to increase taxes on workers, there was modest rise in taxes on the wealthy, but the lion’s share came from employers’ national insurance contributions. It will effectively be a tax on workers especially affecting low-paid workers because the rise in thresholds has a bigger impact on the lower-paid. Employers face a triple whammy from this budget. A higher minimum wage, higher national insurance rates and new labour market regulations. On their own, there is logic to each policy. Fears over the minimum wage causing unemployment have often been misplaced. But, given the economy’s weakness, it is a big burden, which could hold back growth. The budget also exacerbates the distortionary impact of UK tax system, encouraging firms to move to self-employment where NI isn’t paid. The budget had big sums, but there was no boldness to sweep away distortionary effects, such as 100% marginal tax rates for some families, and high stamp duty slowing down the housing market. If anything higher stamp duty will worsen the cost of housing for hard-pressed renters. By the way if you take into account housing costs on disposable income, there are pretty grim forecasts for the next decade.

The basic problem is that government spending is growing rapidly and it is only go to accelerate because of an ageing population. Pension spending is set to increase by 33% over the next decade. There was an extra £22 billion for health care, but in the absence of any productivity improvements will it be enough? Healthcare spending is set to soar to 13% of GDP. The problem is that in three years time, there will still be the need for more spending.

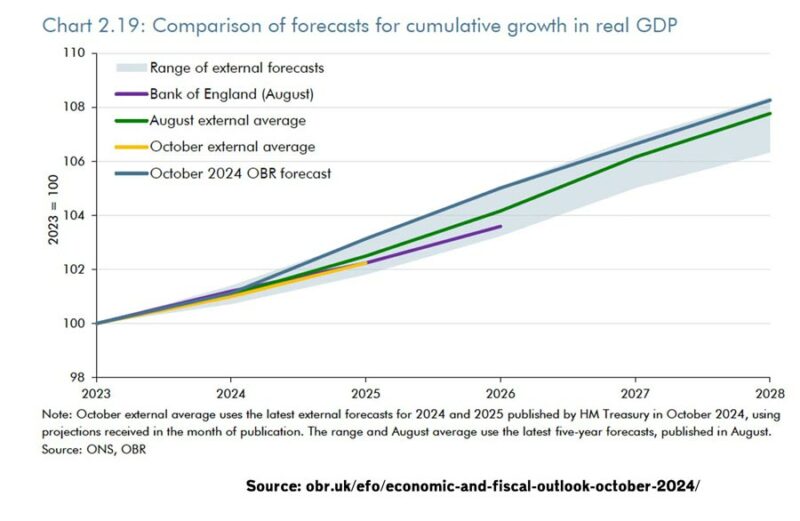

The government is relying on higher economic growth to boost tax receipts like the post-war period. But, the OBR so far have done very little to update their economic growth forecasts. There are three problems. Firstly the OBR was already the most optimistic. Secondly, the effects of higher investment are forecast to have only a small effect in short term. Thirdly, and most worryingly the OBR model the UK economy is already close to full capacity. Because of higher spending and borrowing the budget is expansionary. This means more spending will be injected into the economy. But, they argue this will lead to a small output gap. Given economic growth is very low, this is worrying. You can’t boost economic growth if productive capacity is not increasing. One reason for low growth is the continued forecast fall in participation rates. This means fewer people are able or willing to work. This is the fourth major problem facing firms. Difficulty in recruiting workers.

Spending Tricks

The other hidden problem of the budget is that the new government have repeated many of the tricks of the previous governments. Temporary fuel duty cut has been maintained, but there is a fiction it will rise with inflation in future budgets. If you can’t rise petrol taxes in the first budget, when petrol prices have slumped, you can’t see them ever going up. Even a modest rise in fuel duty would fund cheaper bus fares. As usual environmentally friendly forms of transport rise faster than inflation, but this will only worsen the costs of congestion and pollution on the roads. Budget departments also face very stringent spending limits in the future, which as usual will be very hard to implement. On the positive side, they did announce higher spending for justice and prisons, a department neglected in the past. Public funding for justice in England and Wales declined by 22.4% in real per-person terms from 2009/10 to 2022/23, it will not be easy to reverse this.

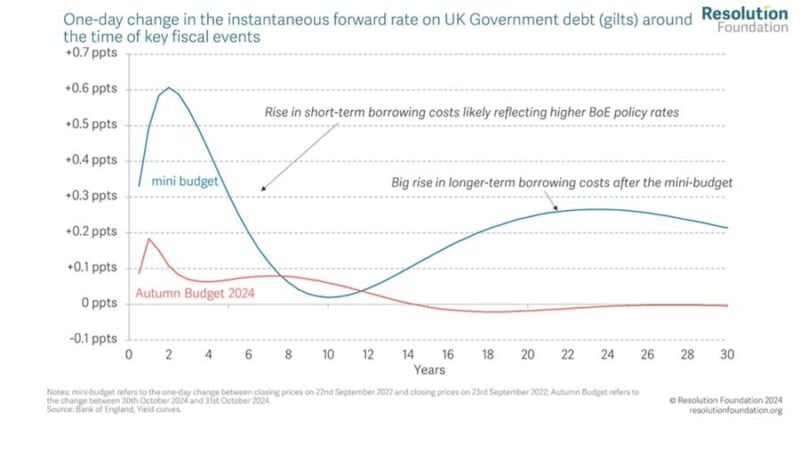

What about the impact on interest rates? The budget definitely saw a small, but significant increase in interest rates as a result of the high spending numbers. Does this mean the UK was close to a Liz Truss-style budget meltdown? Are bond holders getting tired of the size of government borrowing? In short, no. The main reason for the rise in short-term rates is that the higher spending will increase demand in the economy. This means a bigger output gap, more inflationary pressure and hence more pressure on the Bank of England to keep interest rates higher than otherwise. They may cut them this month, but it will be harder to cut interest rates in 2025, if government spending boosts demand. However, long-term bond yields have not increased that much, which means markets are fairly sanguine at borrowing levels.

There is an excellent graph here from the Resolution Foundation. The Truss mini budget saw rise in short-term and long-term borrowing costs. The Reeves budget saw a small spike in short-term borrowing costs, but not long-term borrowing costs. At least for now, markets are calm about levels of borrowing.

There were many missed opportunities in this budget. The unwillingness to at least partially tax bank profit from QE is strange. The original sin though was to go into the election promising to both increase spending and not increase major taxes, this has led to the tortuous efforts to increase taxes from a variety of sources. In the end, they increased NI anyway.

The HM treasury have produced a graph showing a seemingly big gain in living standards, especially for low-income groups, they arrive at this by including the benefits in kind of higher spending on public services. I’m not sure this will be reflected in households’ personal lives.

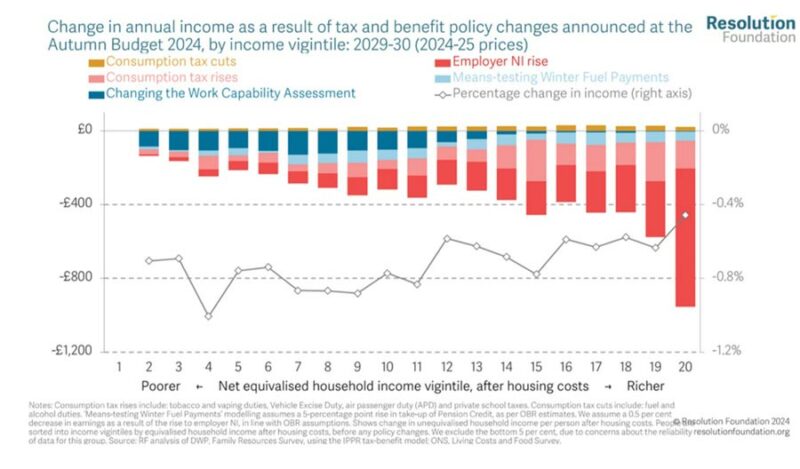

A more realistic impact is given here by the Resolution Foundation which shows the tax and benefit changes will lead to loss across the income spectrum. Although the richer deciles have the biggest income loss, as a share of income. It is the 4th poorest decile who will see the biggest income loss. This is the kind of income decile who just miss out on things like means-tested winter fuel. Another concern of budget is the disincentive effect of so much means tested benefits. I have a friend recently retired, who thinks it’s no longer worth working because you’re better off not working and getting more benefits. No wonder participation rates are low.

The truth is that so much will depend on factors beyond the chancellor’s control. Will households start spending their savings, which have actually increased significantly since covid. What will happen to the global economy?

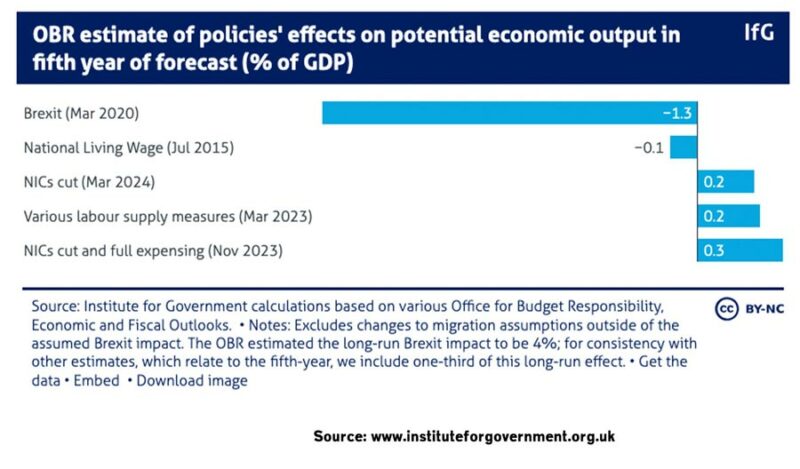

The OBR still models that the negative impact of Brexit will outweigh other much small changes. The truth is that although taxes have risen, they will probably need to keep rising. Sources: