Back in 2010, when Nick Clegg was asked about nuclear power he said it was pointless because it wouldn’t be ready until 2022. As it happened, 2022 came and went, with an unprecedented surge in global energy prices. Although this was ironic bad luck, the UK was uniquely unprepared for an energy crisis with its cold, draughty homes, reliance on gas and lack of investment in energy. But Nick Clegg was right about one thing, in 2022 he wasn’t involved in politics anymore, it was someone else’s problem.

The energy crisis highlighted many long-term failures. Back in 2013, the government of Cameron and Osborned pledged to ‘cut the green crap’ and removed environmental levies. This move wrecked the UK’s insulation programme, cutting insulation rates by 90% and adding £2.5 billion to household energy bills. The UK has the worst insulated homes in Europe, worse than sunny Spain and Mediterranean Italy. The UK has the highest share of houses built before the war, single glazed windows still adorn listed buildings. Downtown Abbey might look good but don’t ask about the heating bills. In 2022, the UK spent £100bn on energy imports and the government spent £37bn on subsidising bills. But, in the 2010s despite interest rates close to zero, the idea of investing in insulation or energy sources was a very low priority for a government fixated on austerity.

Drought in Rainy Country

The UK is actually lucky to have many natural resources, oil, natural gas, and a temperate climate with plenty of rain. But, despite one of the highest rainfalls in Europe, it doesn’t mean we can’t manage to run out of water. In 2022 and 23, large parts of the country had a hosepipe ban and reservoirs ran perilously low. The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) warn by 2050 the UK could be 4 billion litres per day short. How can such a wet country run out of water? In the Victorian Age, extensive reservoirs, sewers and water systems were built to meet the growing demands of cities. But the water privatisations of 1989, fractured this holistic approach to water management. The UK’s last completed reservoir was in Carsington in 1992. In the late 80s, privatised water companies were sold with zero debt, but over the next three decades, the new companies prioritised short-term returns, and dividends to shareholders and despite a £80bn increase in debt, only very few reservoirs have even been planned, let alone built.

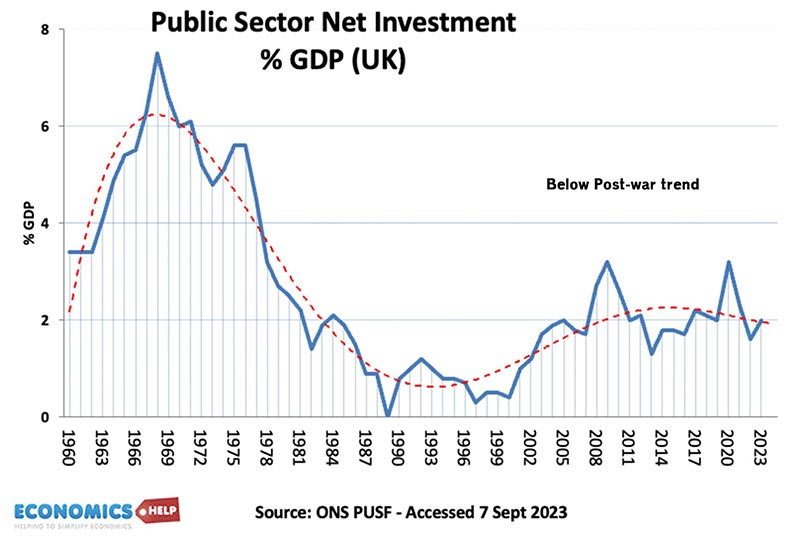

Falling Investment

Overall, the UK’s privatisation programme raised in the region of £70bn, which the government largely used to reduce tax and fund current spending. There was no long-term plan to invest in improving creaking Victorian infrastructure. In the 1980s, public sector investment fell and never really recovered. Even the low current levels of public investment include £40bn of student loans. Whilst European countries have invested in high speed railways, the UK lags behind. The growing population has placed a great strain on road and rail infrastructure. A rare long-term plan was HS2 a link from London to Birmingham and then the north. With depressing predictability, it ran over budget, as resources were diverted to provide cosmetic improvements for constituents in its path. In the event, the project was partially cancelled, leaving a rump to Birmingham but no solution to the predicted travel demand in the north. In a typical act of political short-sightedness, after cancelling the project, the Prime Minister Sunak ordered a sale of land to prevent a future government from reversing the decision. It’s been a recurring theme of the past four decades sell off the family silver for a quick buck, whilst problems slowly but remorselessly build up. A similar lack of forward planning has left prisons full, courts delayed and a justice system creaking at the seams.

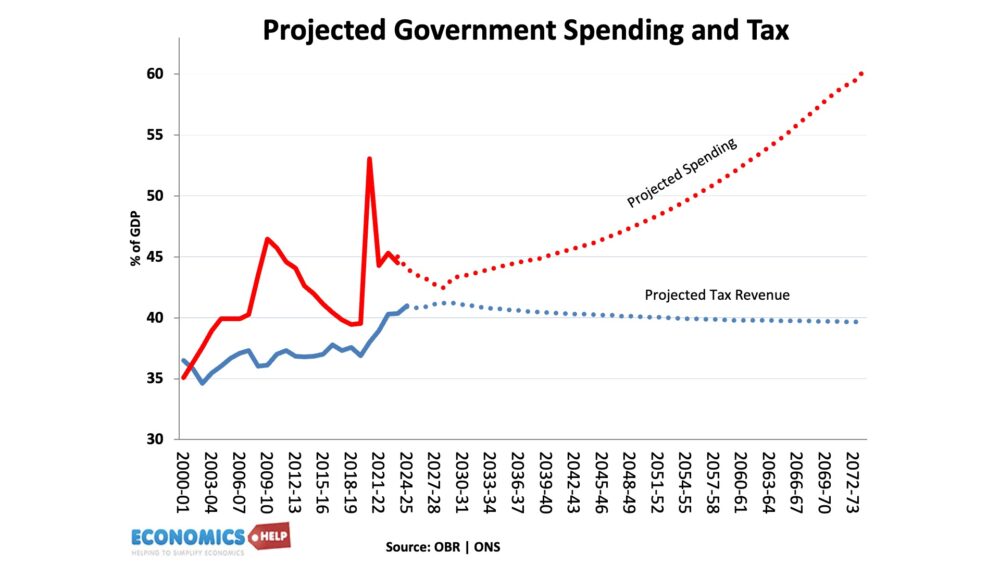

Future Problems

But, if you think that is bad, you haven’t seen anything yet. The forecasts for future tax and spending are pretty grim. The OBR Forecast that on current policy government debt is forecast to soar. Even without more external shocks debt is predicted to reach levels, not seen a since the major war. If this debt was being used to fund investment it would be less worrying, but it isn’t. It reflects the growing cost of an ageing population and rising demand for health care. Pension spending is set to soar, there was never a state pension fund. When the government tried to save a tiny fraction of £1.5 bn by cutting winter fuel allowance for relatively better-off pensioners there was a political backlash. It’s hard to promote long-term solutions to social care, pensions and health care when voters expect to maintain the kind of spending and tax levels, the recent economy is struggling to support. In this regard, the UK is far from unique. In fact the pension crunch will be worse in Italy and France.

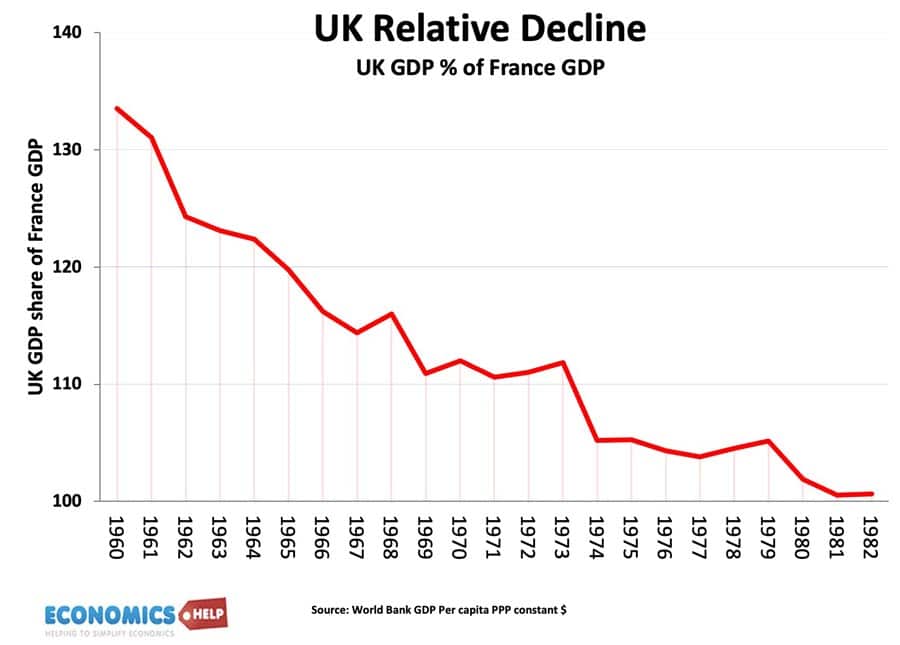

Post-war Decline

In the post-war period, the UK was still an economic powerhouse. In 1950, the UK was the world’s second largest car producer and the world’s biggest exporter. But, resting on its laurels, it failed to keep up. UK productivity lagged behind its rivals and within two decades, its car industry was on its knees, hobbled by strikes, poor management and lack of investment. British cars just didn’t work very well.

By the 1970s, the UK was undergoing an economic crisis, high inflation, strikes and humiliatingly an IMF bailout. It was against this backdrop that the discovery of North Sea Oil was incredibly well timed, the Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan declared that oil was “God’s gift to the British economy”. But, if oil was a gift from above how was it used? Whilst Norway’s government kept 50% ownership and high taxes, they have been able to build a sovereign wealth fund of $1 trillion – all diversified away from fossil fuels. There will be no pension crisis in Norway. Under Thatcher, the UK prioritised tax cuts. You could argue that the UK’s 83% highest tax rate was damaging incentives to work and trade unions needed reform. But, whilst that may have been true, the UK also needed investment in many areas from housing to transport and energy. But the 1980s was a decade when the government wished to leave decisions to market forces. There was a minor revival in the UK car industry thanks to Japanese investment.

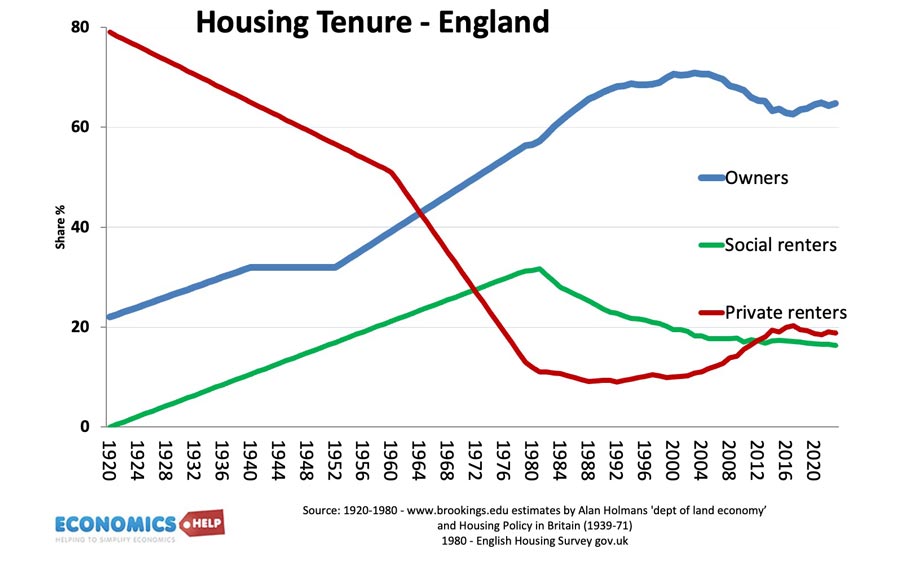

Social Housing

But, in housing Thatcher’s signature policy was selling off social housing to tenants. In 1979, social housing was 30% of all households. But over the next decade 1.6 million were sold off and not replaced dispite a booming population. The proceeds from the sales could have been used to build new housing, but it wasn’t. The policy was very popular with those who bought at a large discount, but it stored up problems for the long-term. In 1980, house prices were three times income, now house prices are 8 times income. Housing has become a luxury good, dependent on parental wealth. The UK has fallen behind in house building, Leaving it to the private sector, homebuilders have been in no rush to increase supply and reduce profit margins. 40% of council homes sold under right to buy are now let in the private sector. Often councils have to pay private landlords to house the homeless. Rising private rents, means the government housing benefit bill reached £25bn two years ago.

Health

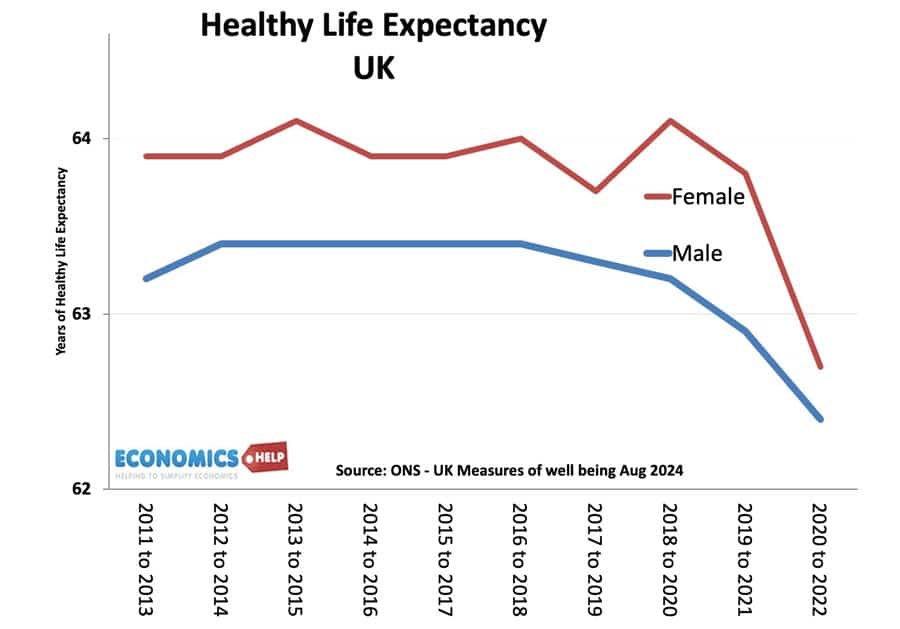

Despite its limitations, the NHS is rightly well-regarded, for providing free health care at the point of use. In fact, bringing together disparate private doctors in 1947, was an example of long-term planning that has paid dividends. But, a service now close to breaking point is also subject to short-term disease. When resources are spread thin and with 7 million on waiting lists. Doctors get to see only acute cases and the solution is to patch up the symptoms and send patients home. What is missing is a long-term solution to deal with rising inactivity and poor health. It is not just covid, we have seen rising long-term sickness across all age groups. The health care system is designed to treat people who come through the doors but preventative treatment is largely off the agenda. There are innumerable ways to improve the nation’s health, improving exercise, cost of healthy food, advertising for junk food, and insecure work. But, efforts to to improve health, like active travel and taxing junk food tend to get drawn into media culture wars and quietly dropped. Prof John Deanfield claims a parallel preventative health service could reduce ill health by 33% and potentially increase GDP by £320bn over 20 years.

Migration

In the past decade net migration has caused over 60% of the growth in the UK population Largely working age, net migration tends to improve public finances, which is a boon to chancellors trying to balance the books. But, net improvement in public finances has not translated into improved public services or more housing, making the public sceptical about the supposed economic benefits of migration. If the population grows, you do need to invest in long-term services.

Private Sector

It’s not just the government sector which is subject to short-termism, private business too are struggling to invest. Firstly, UK companies are more influenced by shareholders and the stock market rather than investors who look to the long term. A trend worsened by an explosion in executive pay linked to equity and stock options. With a strong profit incentive there is a temptation for CEO’s to cut back on research and development and boost share prices in the short-term, to get a bigger pay check. Whatever the reason, the UK clearly has a low level of research and development, something which has held back long-term growth.

UK Business argue it is not so much short-termism on their part, but frequent policy change and crisis, which make it difficult to invest.

Related