After decades of high inflation, economic crisis and a stagnant economy.

The new Argentinian president Javier Milei offers a radical plan – end inflation at whatever the cost. He claims that with inflation soaring, Argentina has no alternative but shock therapy. Liberalise markets, slash government spending, devalue the Peso, close the Central Bank and eventually dollarize the economy. It is a libertarian dream. A bold and fascinating economic experiment But, will the short-term pain be worth the long-term gain?

100 Years of Decline

100 years ago, Argentina was one of the richest economies in the world. Its booming agriculture and export sector encouraged mass immigration from Europe. As French, and Italians saw Argentina as a great economic opportunity. Living standards were similar to France and Canada, it was spoken in similar terms to the US. Yet, the devastating impact of the Great Depression and military coup of 1930 started a process of decline which means 100 years on, the economy seems doomed to flit from crisis to crisis. Argentina has received 22 IMF bail-outs over the past 65 years. They’ve defaulted five times and have one of the highest rates of inflation in the world. Something needs to change, but what is that?

Problems

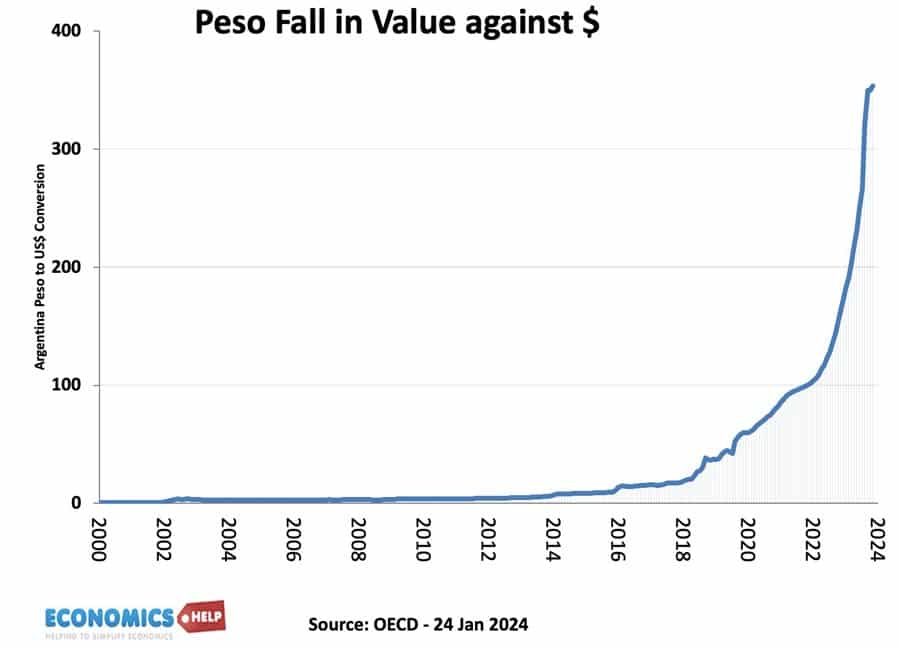

The problem with the Argentinian economy are many. Firstly, it has strong trade unions and generous welfare state, but a failing and weak economy means it struggles to meet payments that workers have been promised. Rather than slash spending, governments of the past have printed money to pay wages. But, this only causes inflation and more instability. To try and keep a lid on inflation, Argentina has a complex network of subsides and regulations trying to fix the exchange rate and limit prices. There was even a time when the government were trying to control inflation by fiddling the inflation statistics. But, the problem is you can’t really control inflation through price controls and it just further distorts economic activity.

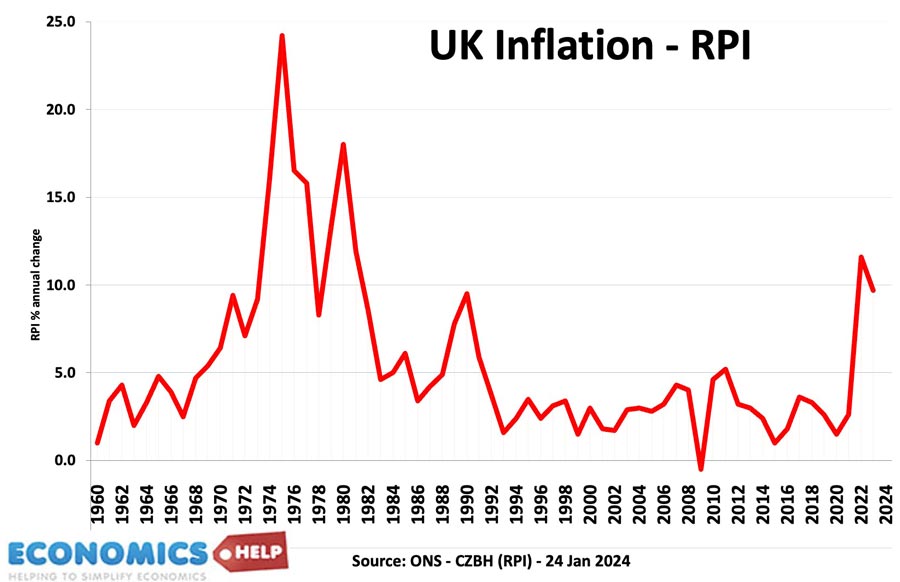

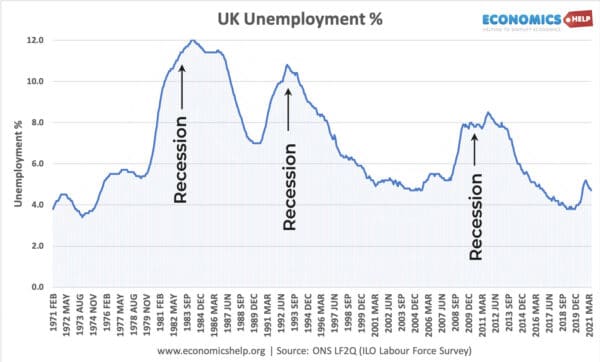

Now interestingly President Milei says one of his economic heroes is Margaret Thatcher. Why? Well in the 1980s, Thatcher introduced her own version of shock therapy to the UK economy. After a decade of high inflation, Thatcher said she would bring inflation under control, whatever the cost. Interest rates went up, money supply reduced and government spending cut. It caused a deep recession and 3 million unemployed.

But, it did bring inflation down and after two years of pain, the underlying inflation was squeezed out of the system. Thatcher also sought to privatise inefficient state industries and remove government regulation. In 1981, 365 economists wrote a letter to the Times saying the government had imposed too much unnecessary economic pain. But, Thatcher kept with her deeply unpopular policies and the economy did recover to have a mini-boom in the late 1980s. Ironically, some observers say she would have lost the 1983 election if it not been for the Argentinian military junta invading the Falklands Islands.

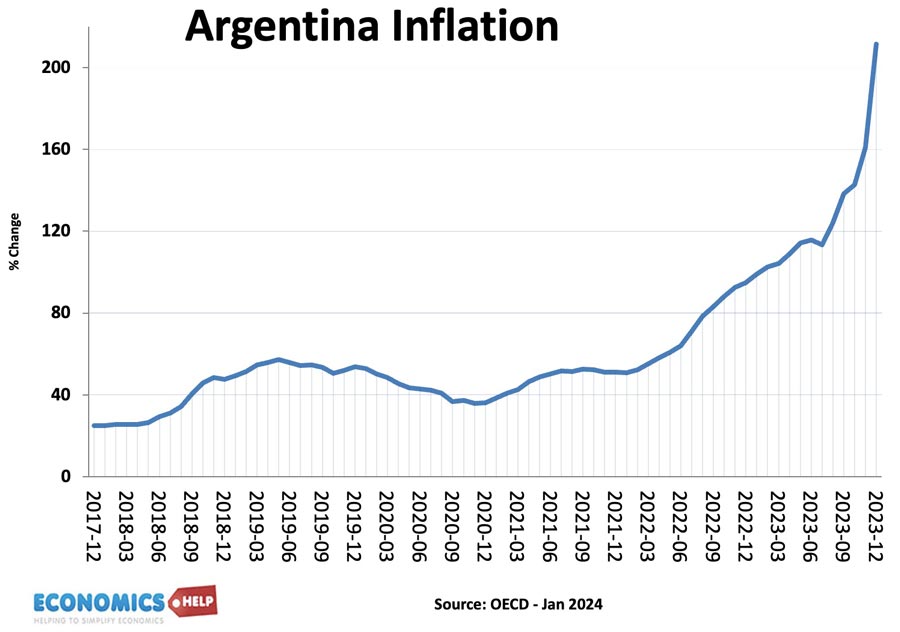

The problem is that the inflation the UK had in the 1980s, was nothing like current Argentinian inflation. At over 200% Argentina’s inflation is spiralling upwards with the system of regulation and subsidies understating the real inflationary pressures. To bring inflation under control would cause a deep recession, profound decline in living standards and major economic disruption. Secondly, Argentina has defaulted on debt so often, that it struggles to borrow in international markets. The government has no room for higher borrowing to help workers deal with a declining economy. In fact, government spending is been cut as part of the shock therapy to reduce Argentina’s reliance on debt and borrowing.

Devaluation

Another problem is that a part of shock therapy is to allow the Peso to float, which has already led to a 50% devaluation. But, in the short-term this causes import prices to rise and a decline in living standards. In the long-term a devaluation may increase exports, although dollarisation would end this route to higher export demand.

Problems of Shock Therapy

The key thing is in the short-term, workers see higher prices, lower wages, a declining economy and cuts to government spending. When you’re struggling to feed your family, promises of long-term benefits to the economy seem scant consolation. To sort out Argentina’s inflation would take a couple of years of painful shock-therapy. In the long-term, lower inflation and lower debt could have substantial benefits, it has the potential to encourage investment and economic growth. High inflation does reduce living standards and discourages innovation and investment. Sometimes, we need to take painful medicine to get rid of disease. There are no pain-free ways to bring inflation under control. But, this particular medicine could cause widespread economic destitution at least in the short-term.

Institutional Weakness

But, even shock therapy and reducing inflation is no guarantee of success. One reason the Argentinian economy struggles so much is institutional weakness. A history of military coups and debt default have made foreign investors wary After the war the Peronian government tried to combat Argentina’s extreme inequality by setting up powerful unions and a generous welfare state. But unlike western Europe, Argentina’s economy was not strong enough to afford its welfare state. The government promised more than it could deliver, setting up a tendency towards higher deficits, bankruptcy and inflation. The tendency to economic crisis has created a political instability and difficulty in introducing long-term reforms. To make a comparison to Thatcher she had a large majority in Parliament, which gave her leeway to stick with unpopular policies.

Decline in Trade

The other problem is that in the post-war period, Argentina placed very high tariffs on imports, protecting domestic industry and reducing its international competitiveness. Argentina has great natural resources such as 21% of the world’s Lithium reserves and fertile agriculture land, but it has not benefitted from this as much as it could. The old saying there is no opportunity, Argentina fails to miss. Long-term reforms need to be more than chocking off demand, but revitalising industry and agriculture to be more competitive.

Dollarisation

Dollarisation is a radical solution to inflation. If you rely on the dollar and get rid of the Central Bank (which Mr Milei calls “the worst thing in the universe”). you remove at a stroke the ability for governments to create inflation by printing money or setting monetary policy.

The problem is that dollarisation only works if you can get enough dollars in the economy. The Economist is doubtful- it claims Argentina would need at least $40bn, but there are no dollars left in reserves, and they are likely to default on existing international debt. Secondly, dollarisation means you give up an independent monetary policy to the US. The concern is that Argentina will find it politically very difficult to reduce government borrowing. But, in a dollarized economy, there is no recourse to inflationary monetary policy, and people will become destitute.

Daniel Raisbeck, a policy analyst at the libertarian Cato Institute, disagrees with the Economist and claim that Argentina already has 50% of the dollars it needs, with some sectors of the economy already using dollars, such as used car sales and real estate.

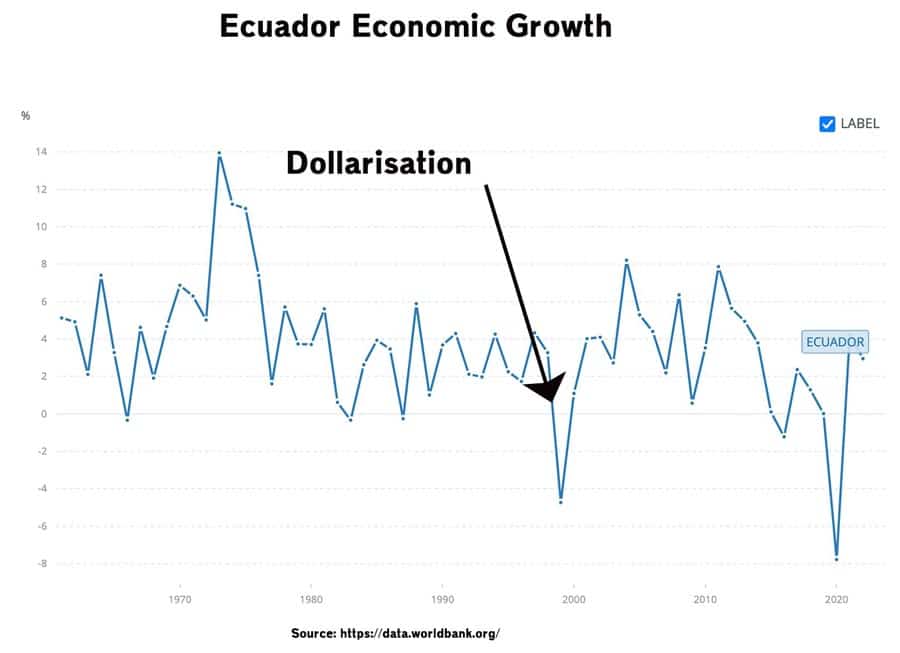

Also, some point to Latin American countries El Salvador and Ecuador as an example of how dollarisation can help stabilise the economies and that Central Banks don’t necessarily need large reserves.

In Ecuador prices initially leaped at first by 91 per cent in 2000 —but then declined rapidly. Since 2003, Ecuador inflation has averaged just below 3 per cent. However there’s been no big growth boom, economic expansion has averaged just below 3 per cent, with per capita GDP actually declining. The economy of Ecuador recorded an average real GDP growth rate of 1.1% in the decade to 2022, below the 1.3% average for Latin America. But, countries that dollarize tend to be very weak in the first place.

In Zimbabwe, dollarisation was introduced in 2009, it arrested Zimbabwe’s chronic hyperinflation, but led to a period of low growth. Not necessarily linked to dollarisation, but a reminder dollarisation is no panacea, but it can at least provide a low inflation environment which can enable other reforms to take root.

Sources: