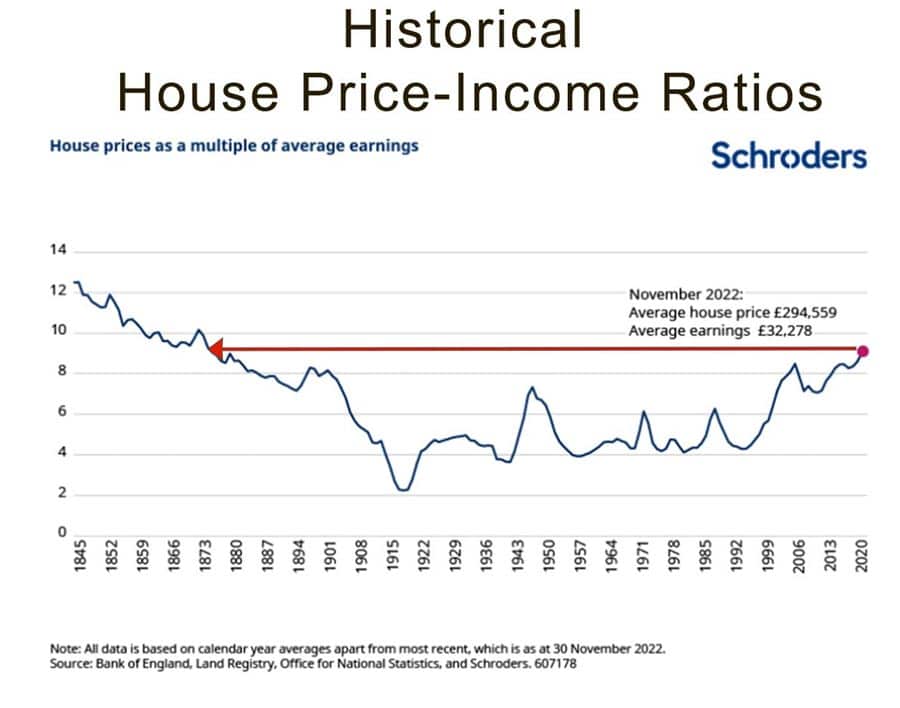

Schroders – 175 Years of House Price History

But, with the ratio of house price to incomes returning to levels last seen in the Victorian age, a new generation remains priced out of the market – flat-sharing and renting into their 40s and 50s. Whilst politicians may promise more affordable homes, the reality is very difficult to change. And this new housing market is having important implications for society. But, first why has the housing ladder been pulled out of reach?

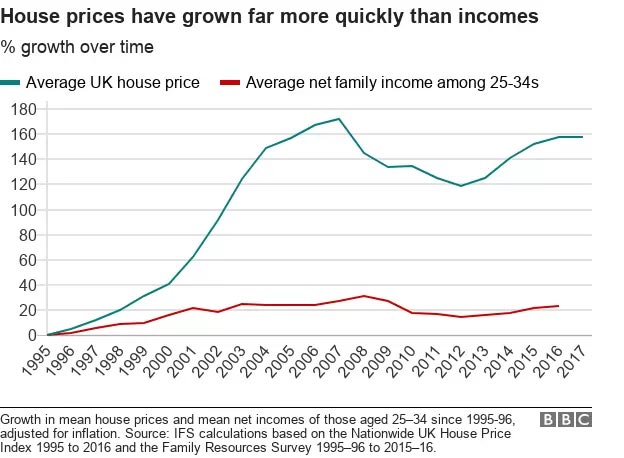

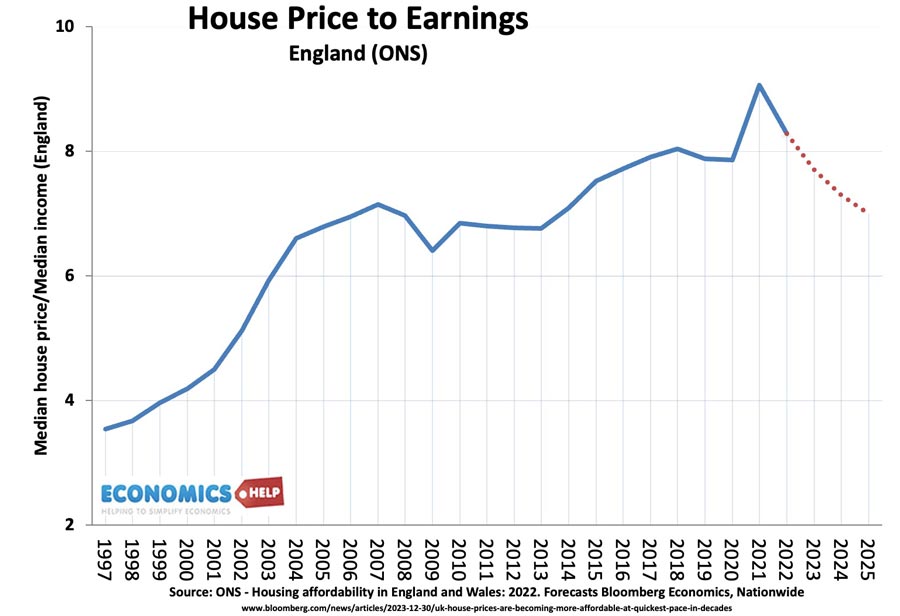

Since the mid 90s, real house prices have risen 160%, but real incomes of the young have only increased 23%.

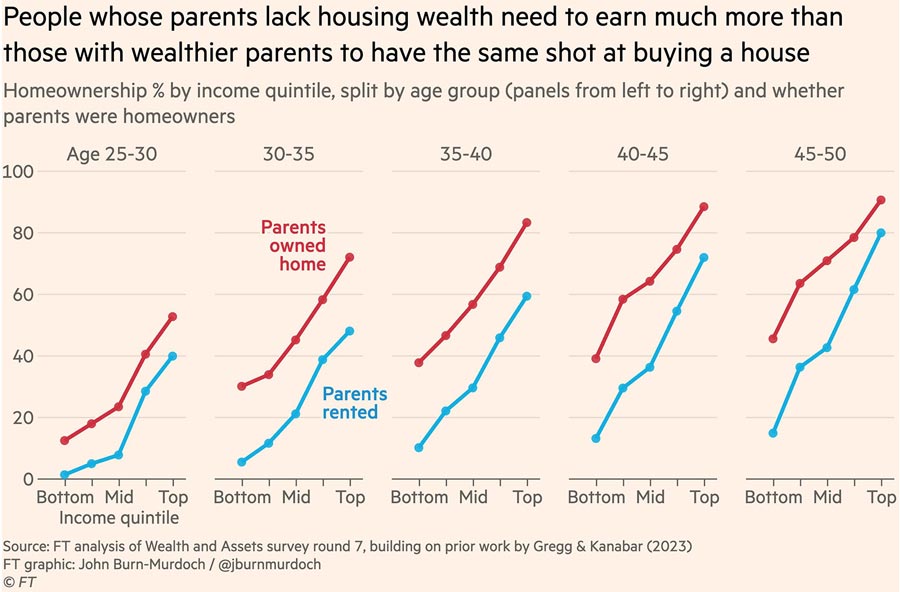

The result is that home ownership has become the preserve of high-income earners or those who receive help from parents.

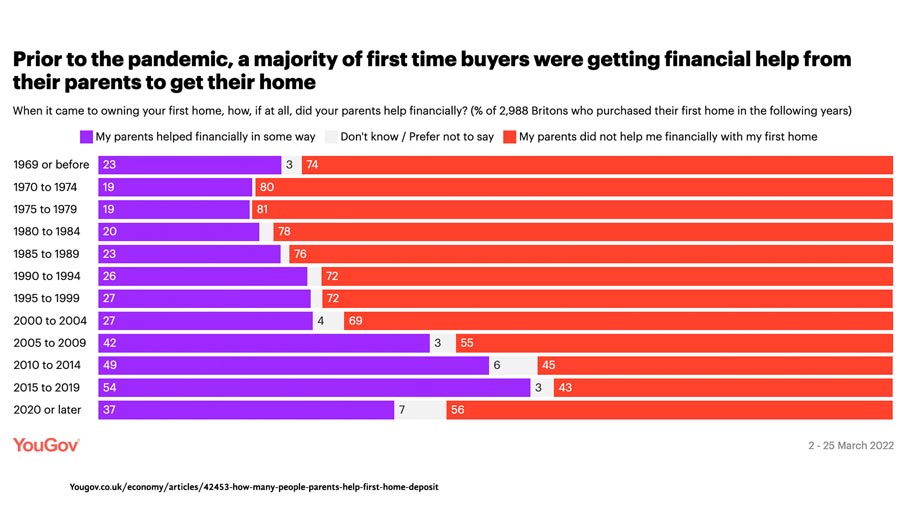

YouGov (not 2020 stats influenced up by Covid)

In 1970, just 19% received help from parents to buy. By 2010 this had risen to 53%. This is an interesting graph from FT, that shows if your parents don’t have wealth, you need to earn around £25,000 a year more to buy a house. Housing unaffordability has led to wealth inequality.

Housing is no longer the great leveller, but increasingly the great divide. House price-to-income ratios are akin to 1870. An age not particularly noted for economic equality.

On the positive side, the ratio of house price to income is forecast to moderately fall in the coming years. This is because of both falling or stagnant house prices, combined with inflation and rising nominal wages. But, seven times income is still nearly double past levels.

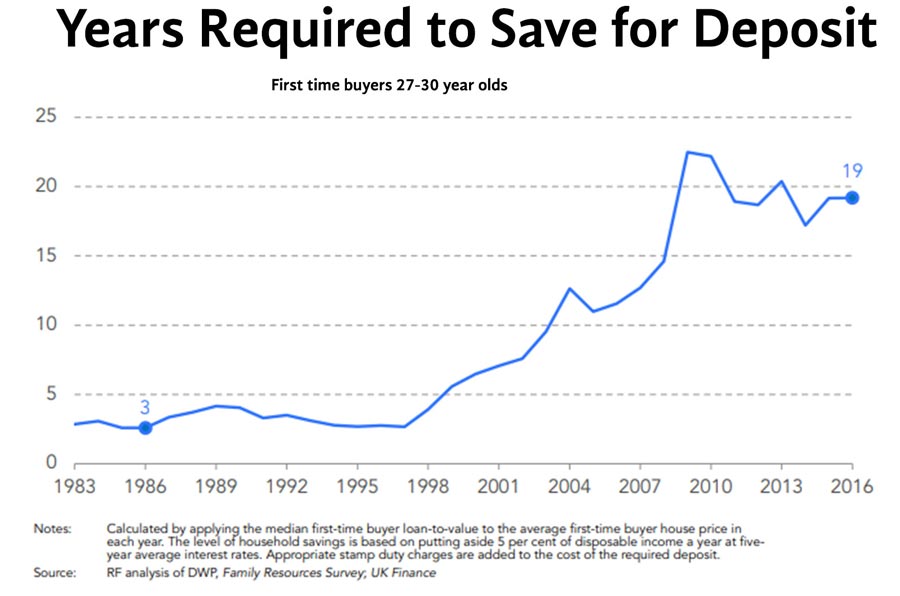

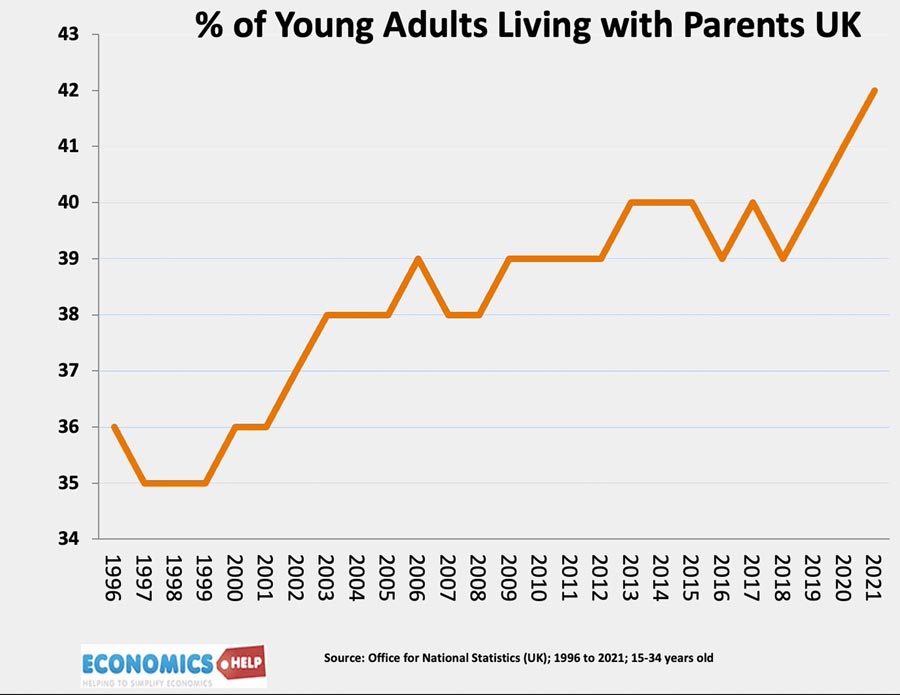

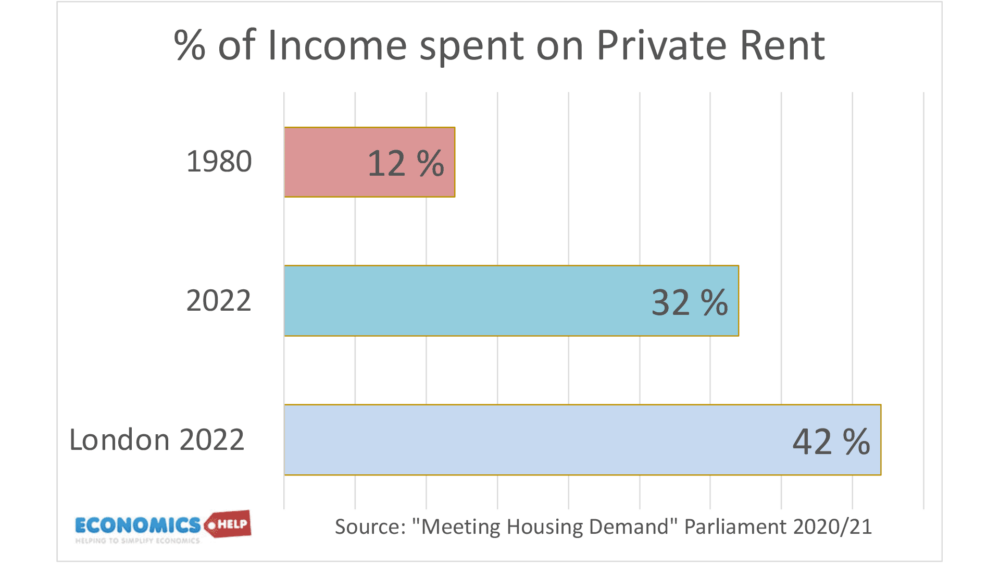

Households in their late 20s, currently face 19 years of saving for a deposit, compared to 3 years in 1986. It has changed living patterns, with a significant rise in the share of young people living with their parents. And it means that the private rented sector has become a life-long destination rather than temporary stepping stone.

Despite higher interest rates reducing affordability for young buyers, the market has been propped up to some extent by wealthy cash buyers and homeowners who have paid off their mortgages.

Why is Home Ownership so Difficult Now

But, if the goal of home ownership is shared across the political spectrum, why is it fading from reality? There are five reasons.

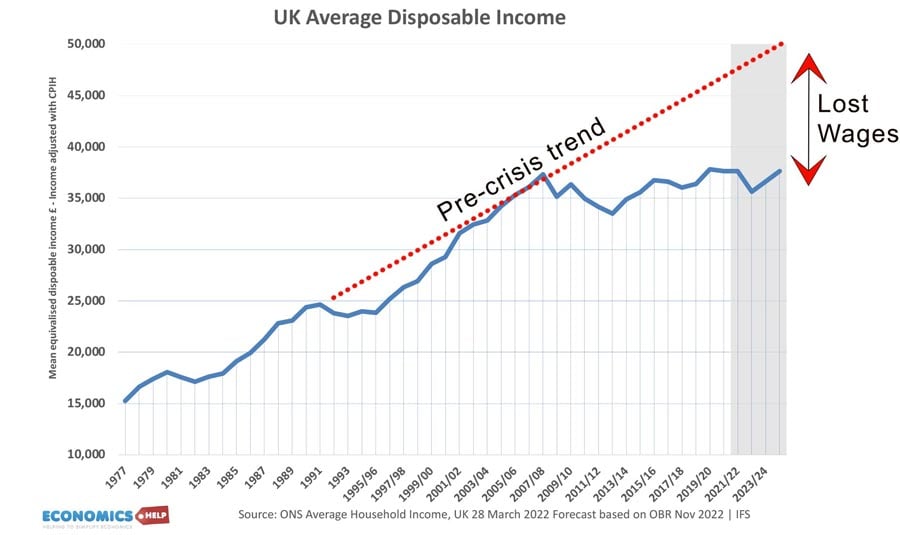

Firstly, the post-war period was a period of rapid growth in real wages. However, since 2010, this growth has abruptly changed, real wage growth has been very limited.

Secondly, in the 1980s and 90s there was a significant deregulation of financial markets. After being tightly regulated, banks and building societies were free to lend bigger income multiples and loosen lending criteria. Self-certification mortgages, mortgages 125% loan to value. The result was that the ratio of household debt rose from under 60% in the late 1960s to a peak of over 180% in 2007. The surge in home buying was reflected by this rise in private debt. However, this growth in credit is exhausted. The 2008 credit crunch and implosion of former building societies like Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley caused a re-valuation of mortgage lending. Mortgage regulation means banks have to stress-test at higher income multiples. It is one reason why higher mortgage rates in 2023, did not cause the same kind of mortgage defaults we saw in the early 1990s and mid 2000s. We are unlikely to see a new liberalisation of mortgage lending and with the withdrawal of government schemes like help to buy, young people cannot borrow their way to home-ownership.

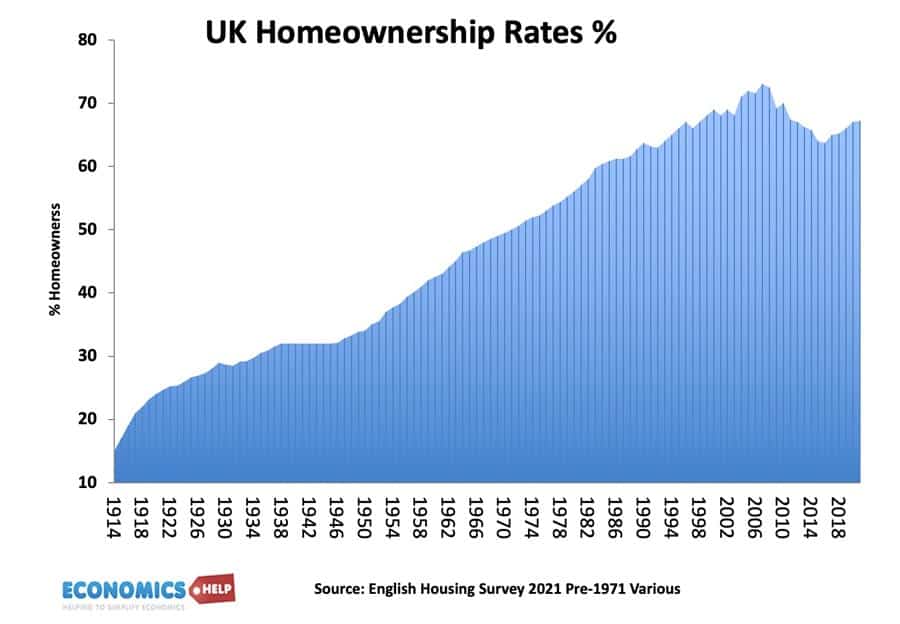

The other factor that helped more people to own their house was the right to buy council house scheme. This enabled 1.7 million households to buy their council house at a below-market price. It enabled a large rise in home-ownership rates in the 1980s and 90s. It was a ladder from social housing to home ownership.

But, the cost of the scheme is that it has severely reduced the stock of social housing, even as demand rose. This was a significant entry point for many households on to the housing market in the 80s, but this route has been exhausted. In fact, the loss of 1.5 million social housing has pushed up market rents and house prices – meaning many low income families are forced to pay market rents.

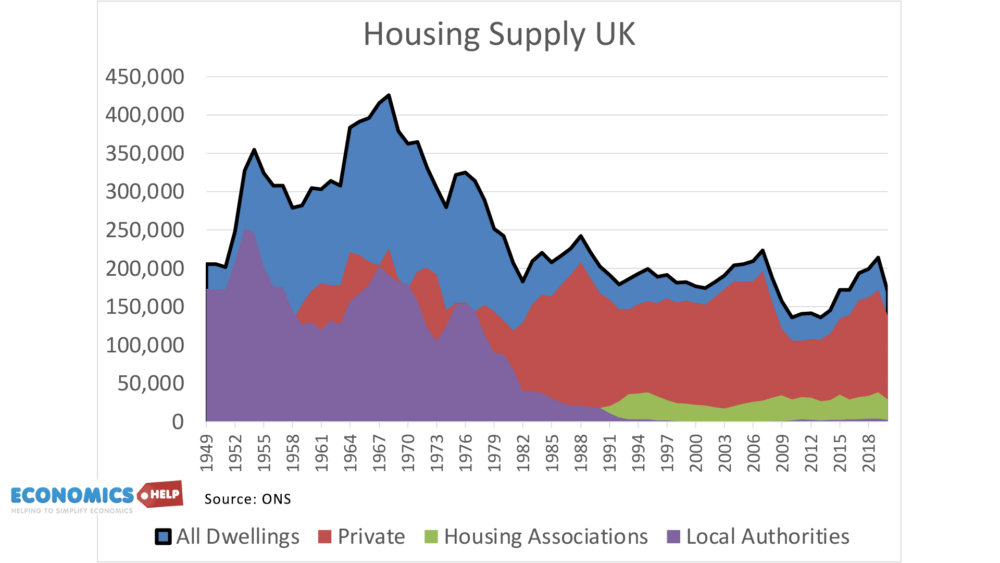

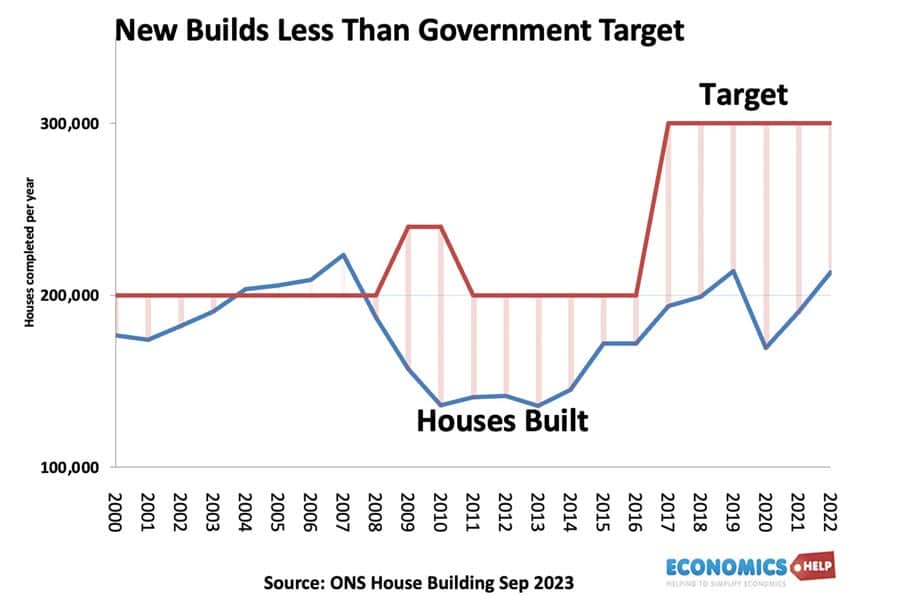

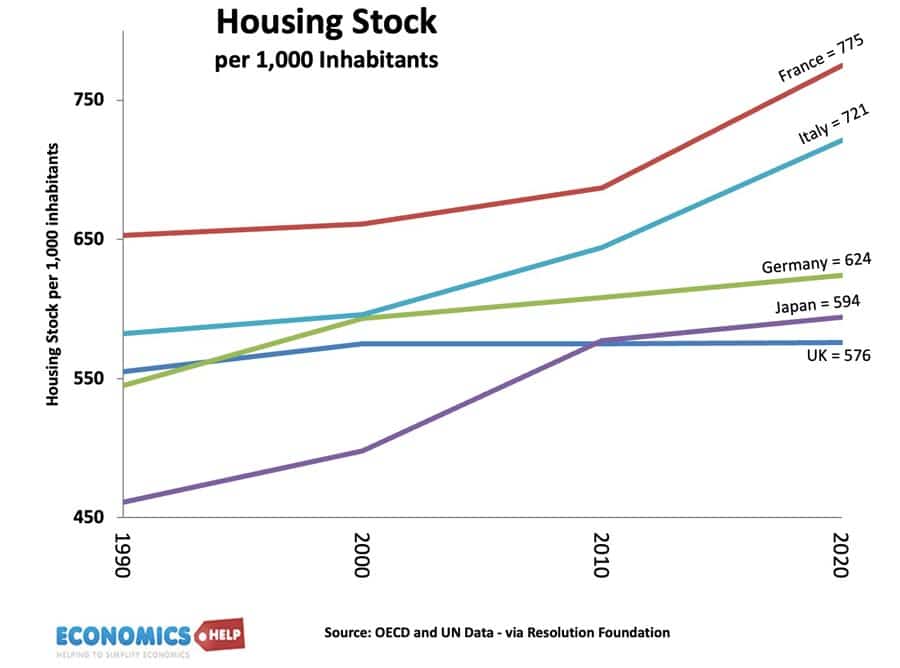

In the post-war period, the UK built homes at a rate of up to 400,000 a year. But, in the past few decades, this has slipped far behind the government’s target and need of a growing population. According to one study, the UK has a shortfall of 4.3 million homes. Compared to similar European countries, the UK has not been building.

The number of homes per inhabitant has fallen behind countries like Italy and France and is one of lowest in Europe. The ratio of empty homes is running at 1%. This shortage of housing is one of the factors, behind high prices, especially in the south east where prices are most overvalued. The problem is that despite promises to build more houses, the past record offers little hope. It is easy to promise building 300,000 homes, but there is a powerful electoral constituency which doesn’t want to see houses built. Labour have promised to be YIMBYs and build, not just on brown belt, but the greyer areas of the green belt. However, even if 300,000 target is met (and I’ll believe it when we see it), it will take years to catch up with shortfall, and will only have a relatively minimal effect on reducing prices. Even a decade of building 300,000 homes a year, will only keep house prices 10% less than otherwise.

What is the impact of this new reality?

Firstly, the pension system relies on the fact that old age pensioners have either paid off their mortgage or are living in cheap social housing. But, in the coming years, we will have a new generation of people over 65 who still face market rents. With market rents averaging over £1,000, this exceeds the basic full state pension (£883 a month), creating a coming crisis of affordability. Pensioner who have paid off mortgage will be completely different situation to pensioners in the private rented sector.

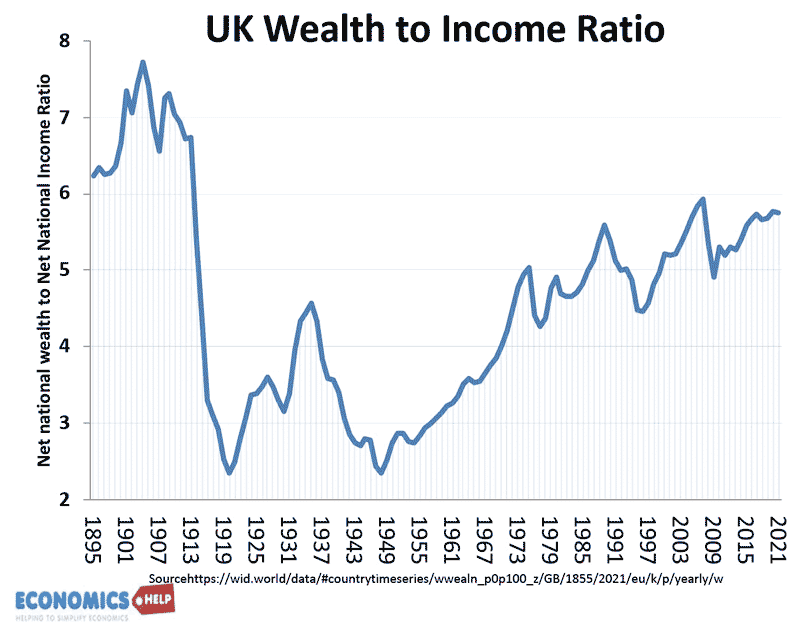

Secondly, the housing market has become increasingly a source of wealth inequality. Household wealth has risen from three times national income in the 1980s to seven times income today. But, the tax system is not designed to deal with rise in wealth. Despite fears of middle England, only 3.7% of households are ever likely to pay inheritance tax.

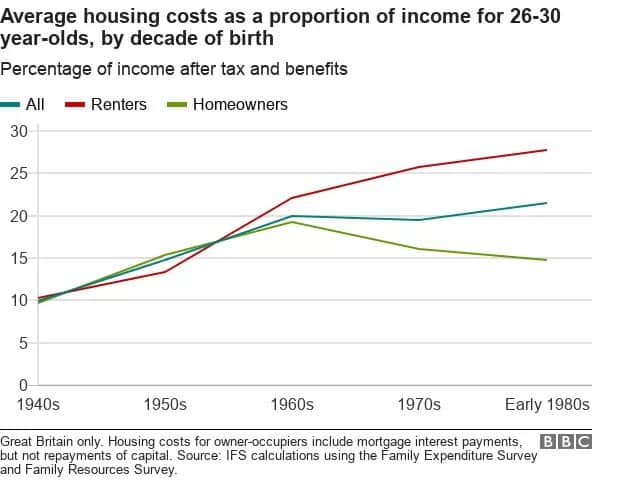

Thirdly, there is a growing sense of frustration amongst younger people, who face stagnant wage growth, and very real housing difficulties. With rent taking up a greater share of income, there is more pressure to work, with more young people taking on second jobs to make ends meet.

Low income households in the private rented sector, increasingly need housing benefit to meet the shortfall. This reached £24bn in 2022. But, in a bid to reduce costs, it has not been allowed to rise in line with rents. The housing crisis is expensive for the government in terms of housing benefit, but also knock-on effects like dealing with homelessness.

Fourthly, it is influencing household formation, with young people living with parents for longer, or living in households bigger than ideal. At the same time, the UK has more single people living in multiple bedroom houses. There is widespread mismatch between under and over-occupancy of the existing housing stock.

Fifthly, with homes more likely to be owned outright by the older generation, there has been greater stagnation in the housing market, with less houses coming onto the market as in the past. Those over 50 are much less likely to move than the 30s generation.

Sixthly, monetary policy is becoming less effective. When the Bank of England want to reduce inflation, they raise in interest rates. Higher mortgage costs reduce spending and inflationary pressures. But, now, we have a much smaller number of households who actually have mortgages, and very few of these have variable mortgages. Therefore to reduce inflation, the Bank have to squeeze a smaller share of the population. The irony, is that higher interest rates have actually caused a large rise in saving income which has benefitted savers. The recent rise in interest rates actually caused a net increase in household income, unlike previous decades. It means monetary policy is less effective and will have unequal effect.

What could be done?

Build more houses, but build them where they are needed, and in higher density. Reform of planning rules could help, but bear in mind there are 1.1 million plots with planning permission agreed but which firms haven’t take up. Building firms complain of high costs and shortage of skilled labour. Addressing skills shortage is important, but relying on market is not enough, the golden age of the UK housing market, was a time when the government was willing to build high quality social housing. Also, other countries who place less emphasis on home ownership do OK. A viable functional renting sector can actually give benefits, such as greater geographical mobility.

Related

Sources:

- Economist – Housing Ladder

- FT – Housing Market

- Britain’s Backlog – Centre for Cities

- You Gov data

- BBC on housing market and young people

- Resolution Foundation

- Schroders 175 years of UK housing market