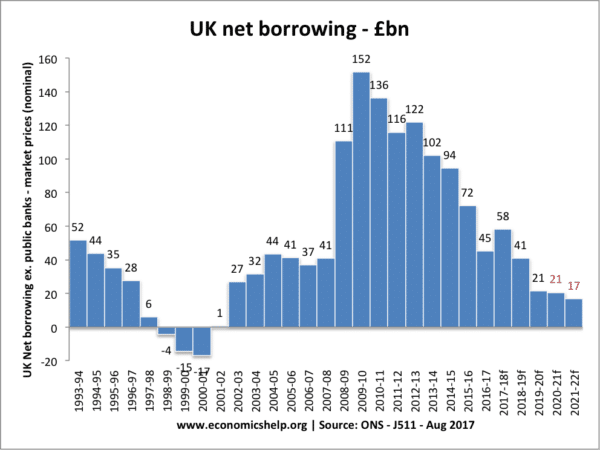

The recent surge in UK government gilts is a warning that unfunded tax cuts in a time of high inflation can cause markets to sell off UK bonds and make it harder to finance future government borrowing. After 15 years of ultra-low interest rates and little concern about rising debt, it is a reminder that there are constraints to government borrowing. Some see the recent fiasco of the UK mini-budget as a warning sign the UK needs to return to austerity – higher taxes and deep spending cuts to balance the budget. But is austerity really necessary now? and was it even necessary in 2010-12?

Yields have come down since government’s u-turn

The austerity of 2010/11

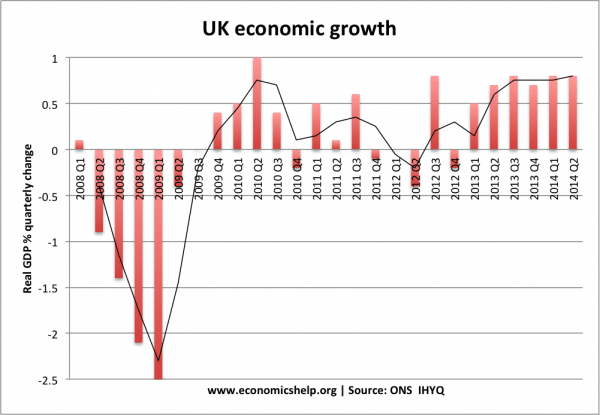

In 2010 many economists warned that the government’s austerity was unnecessary and damaging to the economy (see: Austerity of 2010). These warnings were based on the fact the economy was in recession, inflation very low, interest rates falling, low debt to GDP ratio and cost of austerity to growth and investment.

More detail on why austerity was not needed in 2010

1. UK economy in a recession/weak growth.

In a recession, there is a case for expansionary fiscal policy to offset the decline in private-sector spending.

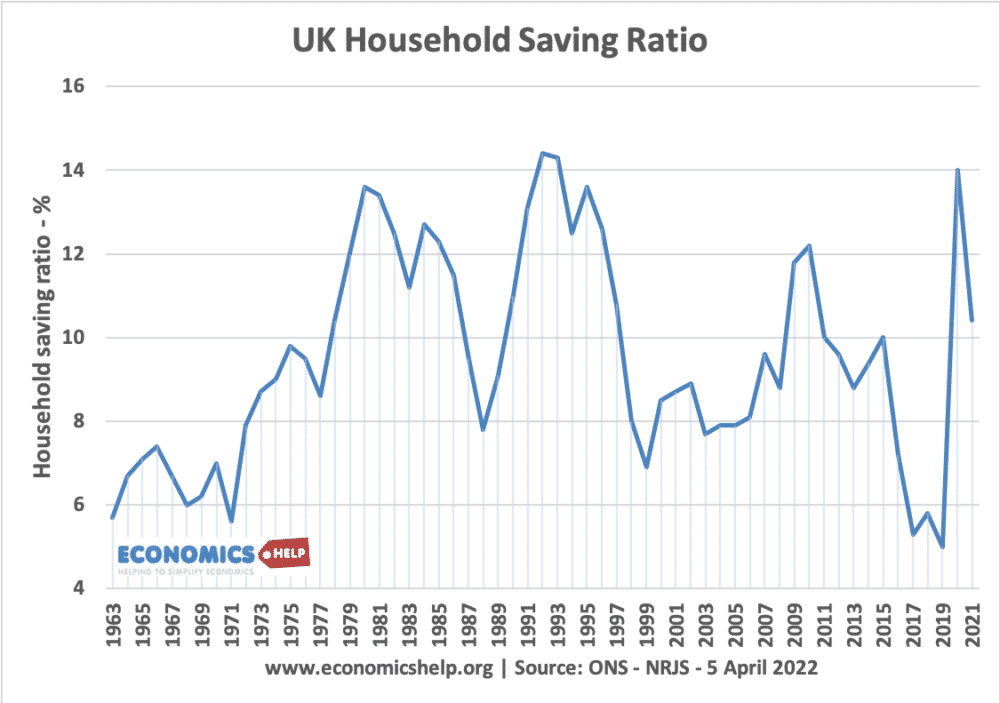

This graph shows how total government borrowing (purple) mirrors the rise in private sector savings. With a rise in private sector savings, there are unused savings, which government borrowing can help to put into the economy to avoid unemployed resources.

UK saving ratio rose to 13% in 2010. In Q2 2022, the UK savings ratio is 7.6% (ONS)

UK finances are not like a household. A rise in government borrowing does not necessarily mean a country is living beyond its means. The government was selling debt to wealthy savers who had spare cash savings. Around 30% of UK debt is held by overseas investors, but importantly they buy UK debt denominated in Pound Sterling.

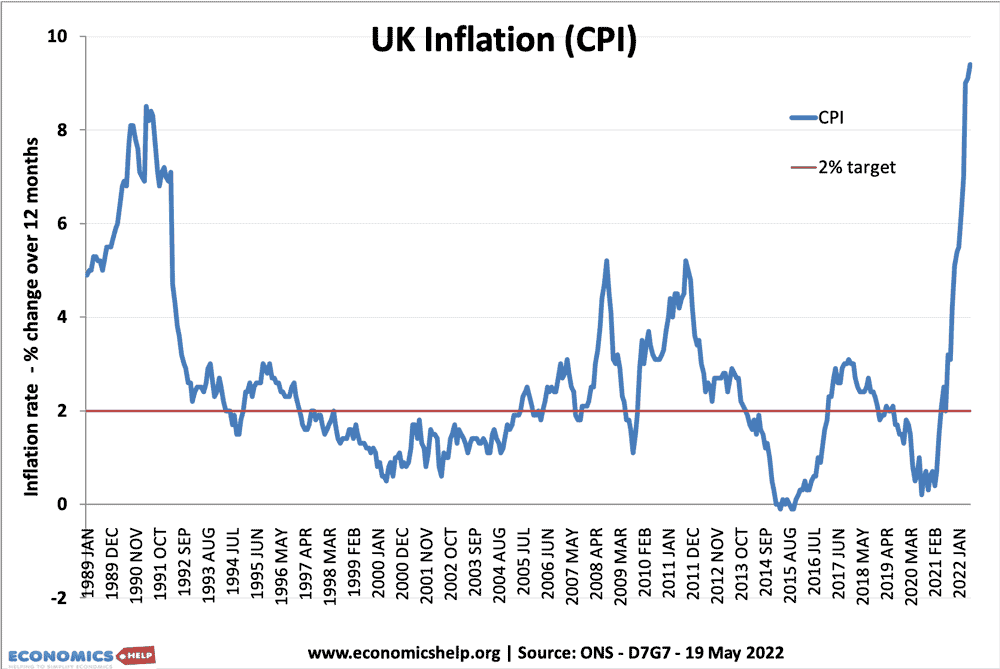

2. Inflation was low

In 2010/15 inflation was close to the government’s target of 2%. There was some temporary cost-push inflation in 2011 (due to the devaluation of the Pound), but underlying core inflation remained unaffected. In a period of low inflation, bigger budget deficits are easier to finance. This is because the expansionary fiscal policy will not add to the inflationary problems. Also in that period, the Bank of England were purchasing gilts through quantitative easing – to try and boost economic growth.

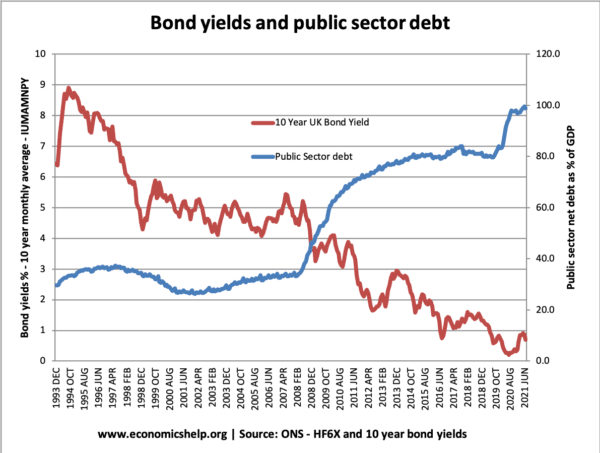

3. Falling bond yields

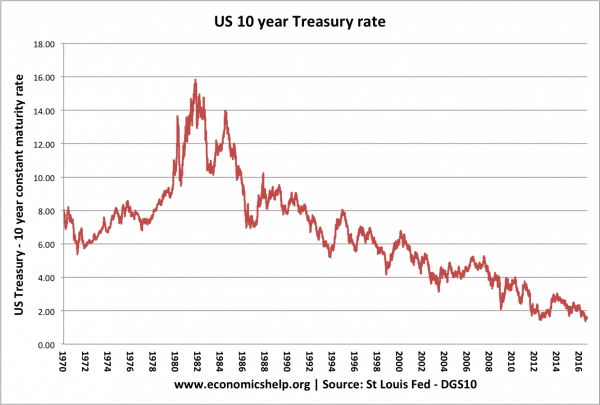

Despite the rise in public sector debt from 40% of GDP in 2008 to 70% of GDP by 2013, UK gilt yields fell. This indicated that the markets had strong demand for buying UK debt and were not worried by growing debt. This reflected the weak UK economy. Both private sector spending and investment was weak so, in the absence of private sector investment, savers had strong demand to buy UK bonds. Supporters of austerity may argue that bond yields only fell because the government took action to reduce the budget deficit. This is unlikely because bond yields were falling across the world. It was a classic liquidity trap with a surplus of savings. UK bond sales were over-subscribed, and there was no shortage of buyers. Falling bond yields were a global phenomenon.

US bond yields fell during the same period.

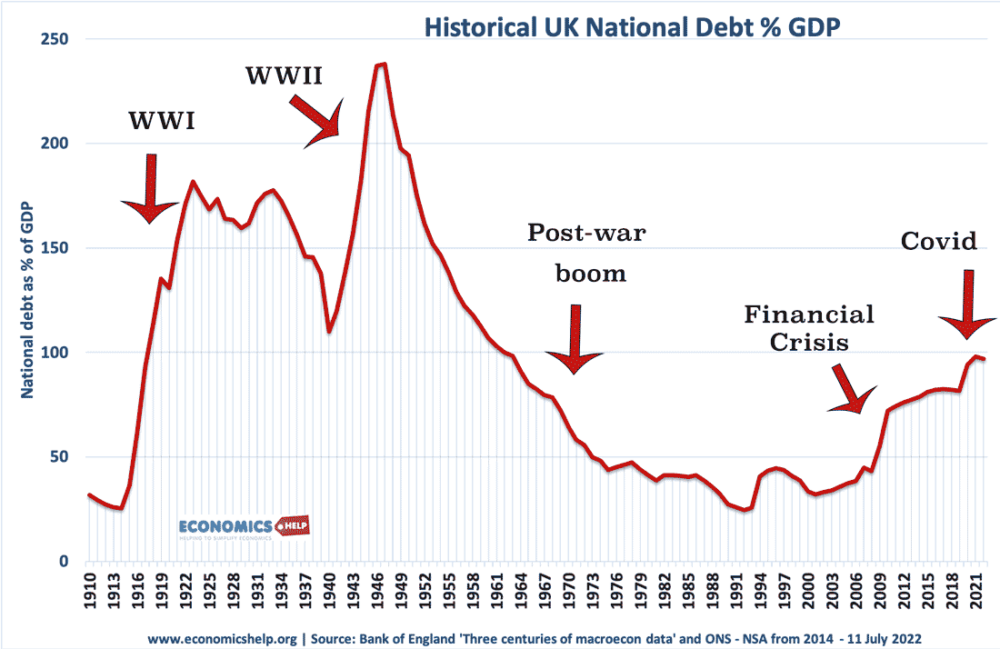

4. UK debt low by historical standards

5. High cost of austerity

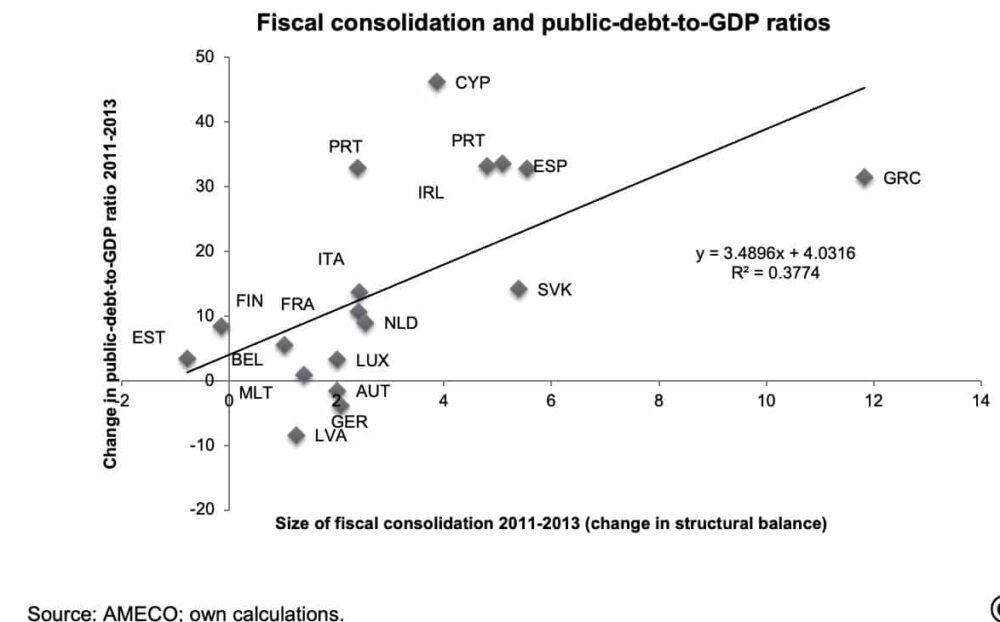

Countries with high levels of fiscal consolidation (austerity) tended to have bigger increases in public debt to GDP ratio. For example, Greece, Portugal and Spain. You could argue it was those countries with rising debt that needed austerity and fiscal consolidation. But, in the case of Greece, Portugal and Spain the fiscal consolidation (combined with overvalued exchange rate in Euro) did lead to lower economic growth, higher unemployment, and thus rise in debt to GDP ratio. (See: Is austerity self-defeating?)

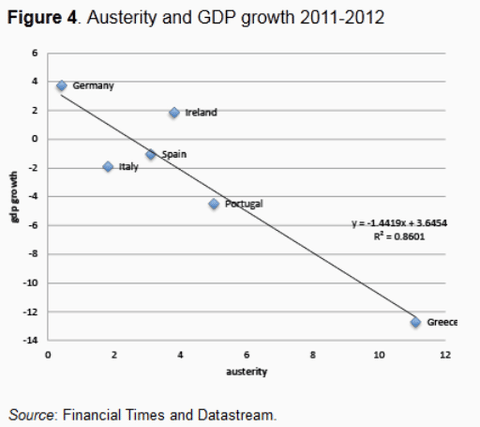

This shows a strong correlation between higher levels of austerity and larger falls in GDP. There is an element that countries with falling GDP were put under more pressure to pursue austerity. For example, Greece in the Eurozone was forced to cut spending sharply. But, the austerity contributed to further falls in GDP.

Are things different in 2022?

There are some differences.

- In 2022, inflation is a real concern running at 10%. This also means the Bank of England is forecast to increase base interest rates (pushing up gilt yields too)

- As a result of high inflation, before the mini-budget, the Bank of England was selling bonds (Quantitative Tightening) that it bought back in 2010. This releases more bonds onto the market, depressing their price (and increasing their yield)

- The economy has become more sensitive to interest rate rises because households and firms have become so used to ultra-low interest rates and house prices have increased faster than inflation.

- Debt is higher at 100% of GDP (though has still been considerably higher than in the past)

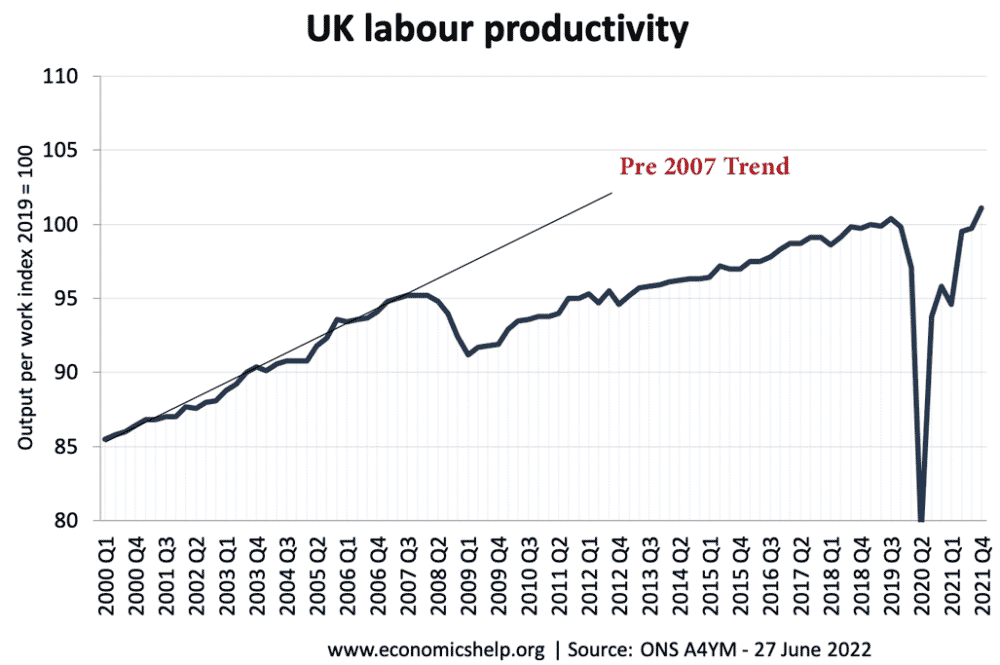

- The outlook for the UK economy is weaker than in 2010. In 2010, analysts expected the UK to return to its long-run trend rate of 2.5% growth that we saw in the post-war period. In 2022, there are reasons to be more pessimistic. Growth has been below trend for 15 years. Problems of Brexit and low productivity suggest growth may continue to be weak. This means the UK cannot rely on strong economic growth to help reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio.

- Demographic factors are more unfavourable with a rising dependency ratio, rise in long-term sickness and decline of net migration from the EU.

Mini-budget in 2010

If the Conservative government had tried a big tax giveaway in 2010, they would probably have gotten away with it. Despite it being the second biggest tax giveaway as a share of GDP since the 1970s and the Barber boom and bust. There wouldn’t have been the same adverse market reaction – primarily because inflationary pressures were very subdued and interest rates were on a downward cycle. The markets could have absorbed the debt, something they are not prepared to do in 2022 because of the different circumstances.

The big question is do we have to resort to austerity in 2022?

By austerity, I will take it to be spending cuts.

Austerity is always a choice. The UK despite its relative decline over the past 15 years is still a wealthy country with high GDP per capita. If the UK wanted to increase benefits in line with inflation it can afford to do so, if the political will is there.

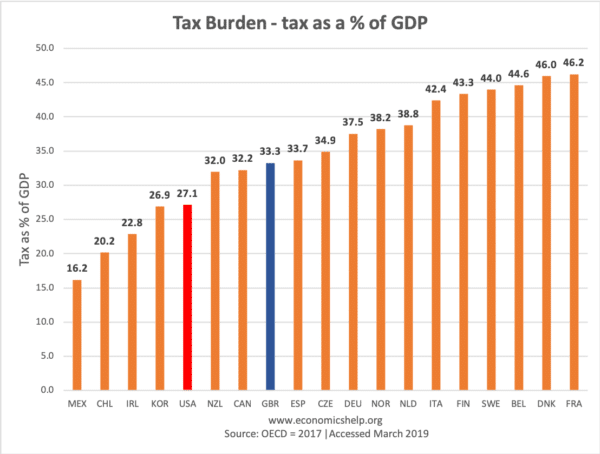

Also, it’s not a very popular concept, but there is a strong link between a higher tax burden and higher standards of living.

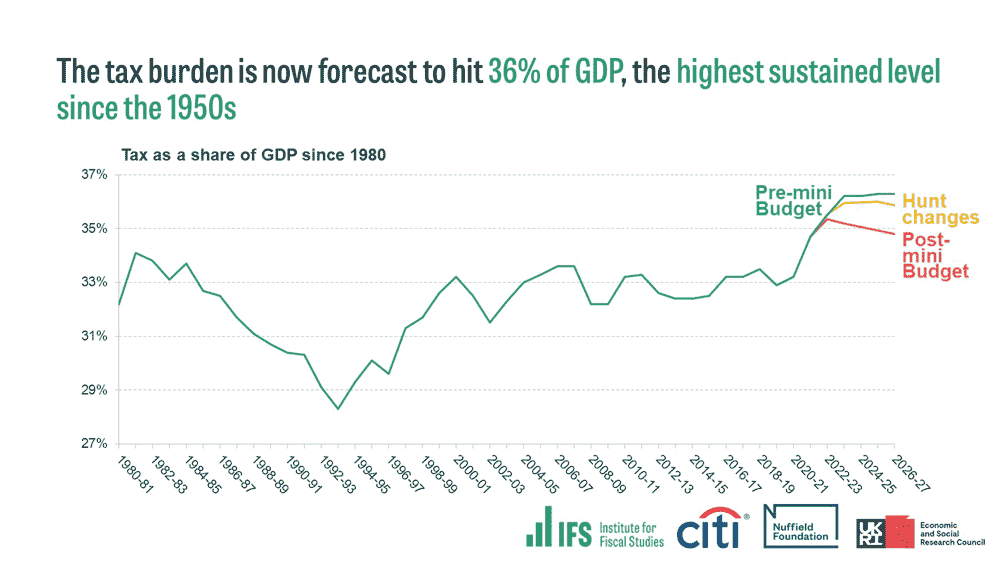

In March 2019, the UK tax burden was 33% of GDP. This has been rising to 36% because of weak GDP growth.

But countries like France, Denmark and Belgium with upwards of 44% tax burden have good standards of living and well-funded health care and social programs. With an ageing population, the UK may need to decide whether to maintain health care and government spending or pursue a more privatised model like the US. But, it is not true that a high tax burden need necessarily be a constraint to growth. It might depend on how taxes are raised.

How much can the UK borrow?

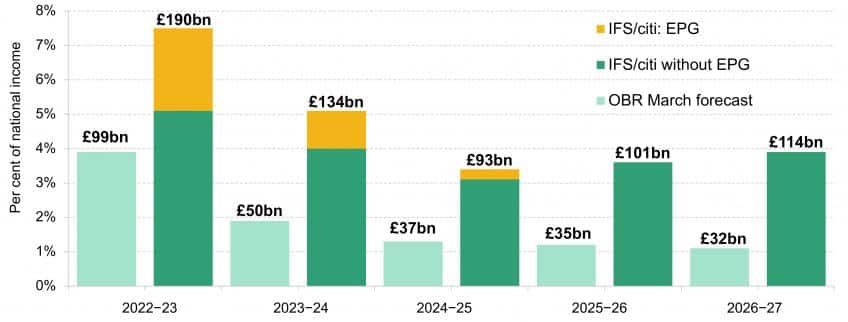

This is a good question. In 2010, it was easier to answer. But, with high inflation and rising interest rates, there are more constraints to budget deficits than 15 years ago. However, if the UK economy does go into recession this winter, there is still scope for some demand management and it would be a mistake to cut the deficit too quickly. A problem with the mini-budget was the sheer scale of tax cuts on top of a very generous energy price guarantee.

The mini-budget proposed a £100bn increase in government borrowing at a time of high inflation and rising interest rates. This was reckless. Also the markets probably realised tax cuts for the rich in a time of cost of living crisis was politically unsustainable. This may explain some of the market sell-off.

Other solutions to austerity

Replace the Energy price guarantee with direct payments. Setting price controls gives much greater benefit to rich households because they use more electricity and gas (bigger houses, more appliances). Therefore, it is actually quite a wasteful use of money. Giving direct income support to those who need it, allows more targetted use of government funds and keeps a very strong incentive to reduce demand (something we need to do for many reasons)

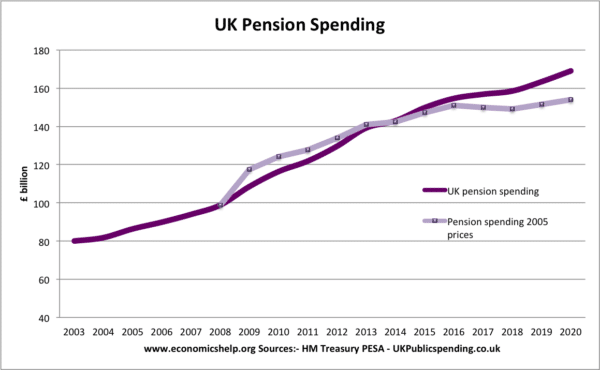

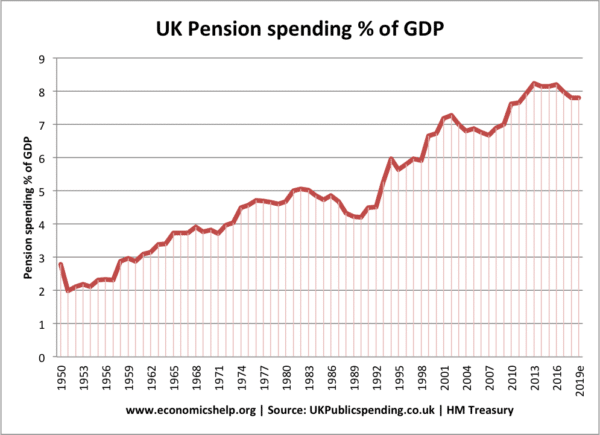

Triple-lock guarantee for pensions

For political reasons, pensioners have been guaranteed a triple-lock guarantee which means pension spending has been rising faster than in many other areas, causing pressure on other areas of government finance. Rather than finding spending cuts from the usual suspects (e.g. universal credit, health, education, defence), one solution is to limit the growth of pension spending, possibly through reducing payments (and or higher taxes) or the richer pensioners who own their own home and have good standards of living.

Further reading